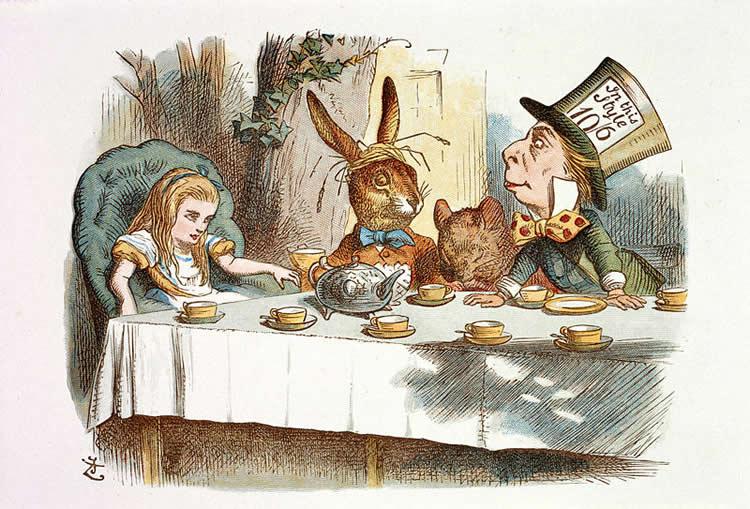

Most reputable doctors tend to refrain from diagnosing people they’ve never met or examined. Unfortunately, this circumspection doesn’t obtain as often among lay folk. When we lob uninformed diagnoses at other people, we may do those with genuine mental health issues a serious disservice. But what about fictional characters? Can we ascribe mental illnesses to the surreal menagerie, say, in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland? It’s almost impossible not to, given the overt themes of madness in the story.

Carroll himself, it seems, drew many of his depictions directly from the treatment of mental disorders in 19th century England, many of which were linked to “extremely poor working conditions,” notes Franziska Kohlt at The Conversation. During the industrial revolution, “populations in so-called ‘pauper lunatic asylums’ for the working class skyrocketed.” Carroll’s uncle, Robert Wilfred Skeffington Lutwidge, happened to be an officer of the Lunacy Commission, which supervised such institutions, and his work offers “stunning insights into the madness in Alice.”

Yet we should be careful. Like the supposed drug references in Alice, some of the lay diagnoses now applied to Alice’s characters may be a little far-fetched. Do we really see diagnosable PTSD or Tourette’s? Anxiety Disorder and Narcissistic Personality Disorder? These conditions hadn’t been categorized in Carroll’s day, though their symptoms are nothing new. And yet, experts have long looked to his nonsense fable for its depictions of abnormal psychology. One British psychiatrist didn’t just diagnose Alice, he named a condition after her.

In 1955, Dr. John Todd coined the term Alice in Wonderland Syndrome (AIWS) to describe a rare condition in which—write researchers in the Journal of Pediatric Neurosciences—“the sizes of body parts or sizes of external objects are perceived incorrectly.” Among other illnesses, Alice in Wonderland Syndrome may be linked to migraines, which Carroll himself reportedly suffered.

We might justifiably assume the Mad Hatter has mercury poisoning, but what other disorders might the text plausibly present? Holly Barker, doctoral candidate in clinical neuroscience at King’s College London, has used her scholarly expertise to identify and describe in detail two other conditions she thinks are evident in Alice.

Depersonalization:

“At several points in the story,” writes Barker, “Alice questions her own identity and feels ‘different’ in some way from when she first awoke.” Seeing in these descriptions the symptoms of Depersonalization Disorder (DPD), Barker describes the condition and its location in the brain.

This disorder encompasses a wide range of symptoms, including feelings of not belonging in one’s own body, a lack of ownership of thoughts and memories, that movements are initiated without conscious intention and a numbing of emotions. Patients often comment that they feel as though they are not really there in the present moment, likening the experience to dreaming or watching a movie. These symptoms occur in the absence of psychosis, and patients are usually aware of the absurdity of their situation. DPD is often a feature of migraine or epileptic auras and is sometimes experienced momentarily by healthy individuals, in response to stress, tiredness or drug use.

Also highly associated with childhood abuse and trauma, the condition “acts as a sort of defense mechanism, allowing an individual to become disconnected from adverse life events.” Perhaps there is PTSD in Carroll’s text after all, since an estimated 51% of DPD patients also meet those criteria.

Prosopagnosia:

This condition is characterized by “the selective inability to recognize faces.” Though it can be hereditary, prosopagnosia can also result from stroke or head trauma. Fittingly, the character supposedly affected by it is none other than Humpty-Dumpty, who tells Alice “I shouldn’t know you again if we did meet.”

“Your face is the same as everybody else has – the two eyes, so-” (marking their places in the air with his thumb) “nose in the middle, mouth under. It’s always the same. Now if you had two eyes on the same side of the nose, for instance – or the mouth at the top – that would be some help.”

This “precise description” of prosopagnosia shows how individuals with the condition rely on particularly “discriminating features to tell people apart,” since they are unable to distinguish family members and close friends from total strangers.

Scholars know that Carroll’s text contains within it several abstract and seemingly absurd mathematical concepts, such as imaginary numbers and projective geometry. The work of researchers like Kohit and Barker shows that Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland might also present a complex 19th century understanding of mental illness and neurological disorders, conveyed in a superficially silly way, but possibly informed by serious research and observation. Read Barker’s article in full here to learn more about the conditions she diagnoses.

Related Content:

Lewis Carroll’s Photographs of Alice Liddell, the Inspiration for Alice in Wonderland

See Salvador Dali’s Illustrations for the 1969 Edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

Let us not forget that Carroll suffered himself from a disorder that is covered under the heading philias in the DSM manual, I am referring to his notorius pedophilia.

A hypnagogic hallucination is a vivid, dream-like sensation that an individual hears, sees, feels or even smells and that occurs near the onset of sleep. As the individual falls asleep, for example, he experiences intense hypnagogic hallucinations and imagines that there are other people in his room.Reverie relates to the same sort of hallucinations but on waking up ( I think this is quite a lot rarer than those associated with going to sleep )

They may also be experienced during meditation — or other situations where your mental focus is not on what is actually going on around you ( day dreaming , imagining , lost in your thoughts etc )

A common feature of hypnagogic hallucinations is that parts of your body can change size — so ‚for example , your hands can feel very large — or your head very small . This might be part of ” the drink me ” potion whre Alice experiences huge changes in dimensions and then becomes aware of it’s disadvantages and tries to return to ” normal ” size.

That’s a tired old cliche based on myth