On his way to sainthood as an avatar of love and justice, Martin Luther King, Jr. lost too much of his complexity. Whether deliberately sanitized or just drawn in broad strokes for easy consumption, the Civil Rights leader we think we know, we may not know well at all. King himself ruefully noted the tendency of his audiences to box him in when he began publicly and forcefully to challenge U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War and the perpetuation of widespread poverty in the wealthiest country on earth. “I am nevertheless greatly saddened,” he remarked in 1967, “that the inquirers have not really known me, my commitment, or my calling.”

As WBUR notes in its introduction to a discussion on King’s political philosophy, the “specifics of his radical politics often go unexamined when celebrating his legacy…. His political and economic ideas are clear in his speeches against the Vietnam War and his call to work toward economic equality.”

His radical stances did not sit well with the FBI, nor with many of his former supporters, but their roots are evident in his most-published work, the 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” in which he coined the famous phrase, “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

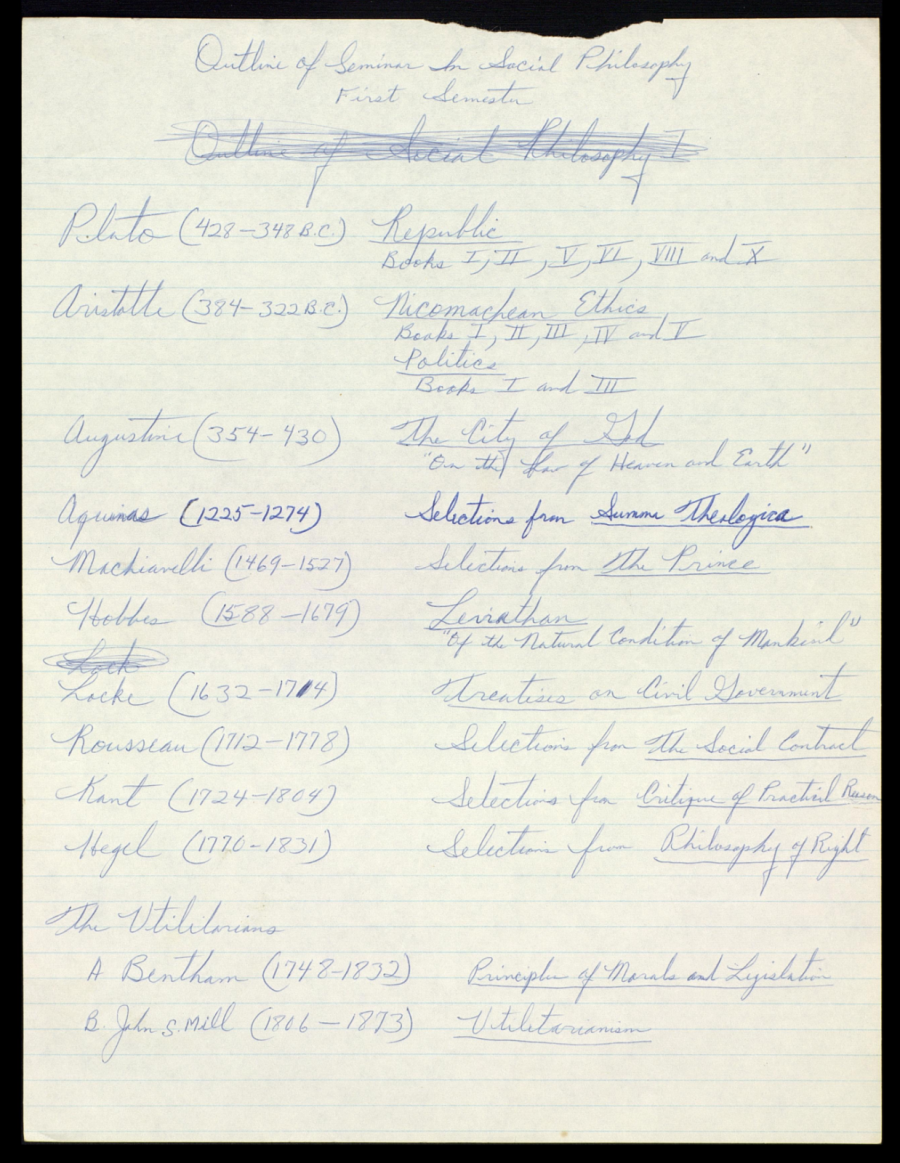

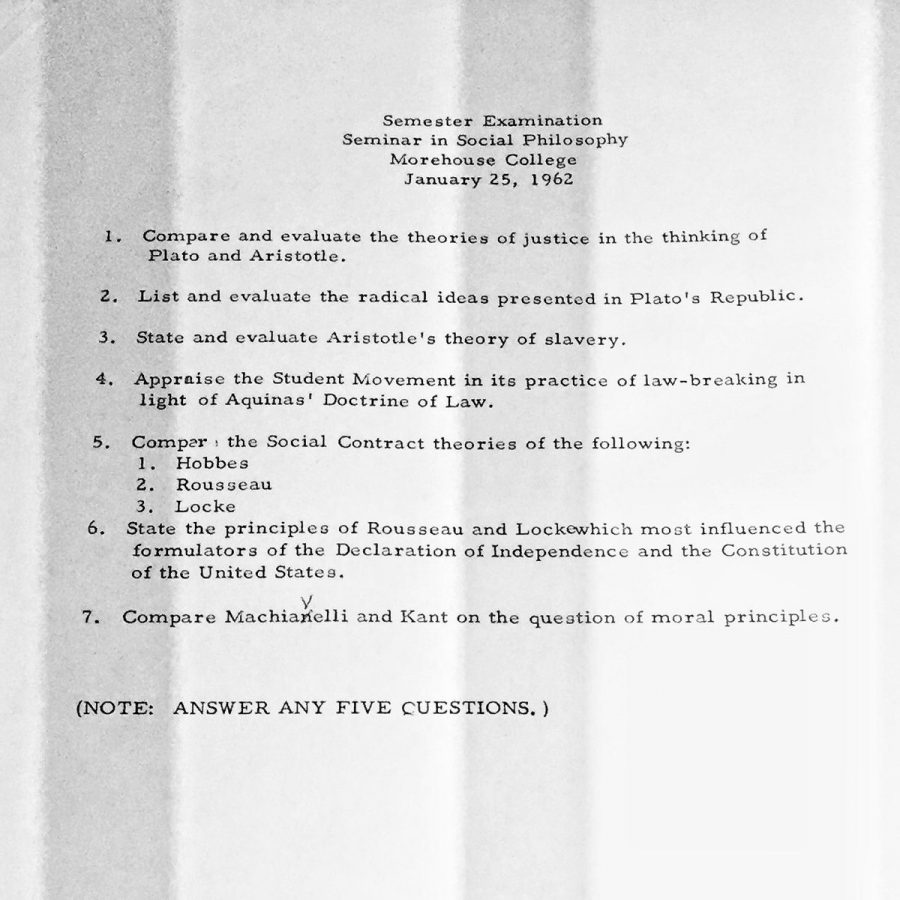

We know of King’s indebtedness to the thought of Mahatma Gandhi and Henry David Thoreau, and of his theological education. He was also steeped in the political philosophy of the West, from Plato to John Stuart Mill. In his graduate work at Boston University and Harvard in the 50s, he read and wrote on Hegel, Kant, Marx, and other philosophers. And as a visiting professor at Morehouse College—one year before his arrest in Birmingham and the composition of his letter—King taught a seminar in “Social Philosophy,” examining the ideas of Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, Aquinas, Machiavelli, Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, Kant, Hegel, Bentham, and Mill.

At the top of the post, you can see his handwritten syllabus (view in a larger format here), a sweeping survey of the European tradition in political philosophy. Further up (or here in a larger format) see a typewritten exam with seven questions from the reading (students were to answer any five). King not only asked his students to connect these thinkers in the abstract to present concerns for justice, but, in question 3, he specifically asks them to “appraise the Student Movement in its practice of law-breaking in light of Aquinas’ Doctrine of Law” (referring to the Catholic theologian/philosopher’s distinctions between human and natural law).

The syllabus and exam give us a sense of how King situated his own radical politics both within and against a long tradition of philosophical thought. For more on King’s political philosophy, listen to Harvard professors Tommie Shelby and Brandon Terry discuss their new collection of essays—To Shape a New World: Essays on the Political Philosophy of Martin Luther King, Jr.—in the WBUR interview above.

via Daily Nous/The King Center

Related Content:

Free Online Philosophy Courses

How Martin Luther King, Jr. Used Nietzsche, Hegel & Kant to Overturn Segregation in America

‘You Are Done’: The Chilling “Suicide Letter” Sent to Martin Luther King by the F.B.I.

On the Power of Teaching Philosophy in Prisons

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

How much of it was plagiarized?