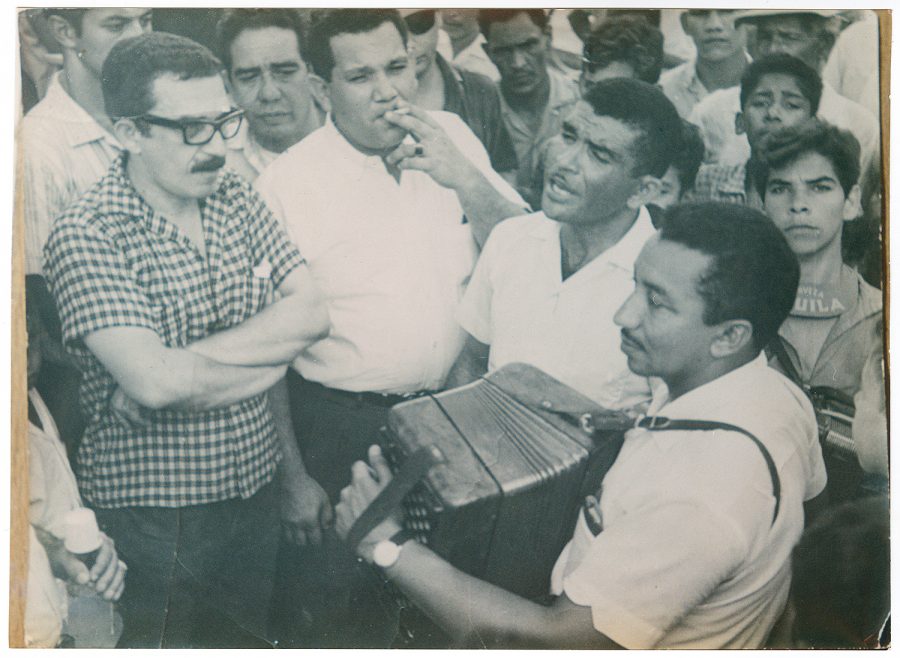

Unidentified photographer. Gabriel García Márquez in Aracataca, March 1966.

Courtesy Harry Ransom Center.

When Gabriel García Márquez died in 2014, it was said that only the Bible had sold more books in Spanish than the Colombian writer’s work: Love in the Time of Cholera, The Autumn of the Patriarch, Chronicle of a Death Foretold, The General in His Labyrinth… and yes, of course, One Hundred Years of Solitude, the 1967 novel William Kennedy described in a New York Times review as “the first piece of literature since the Book of Genesis that should be required reading for the entire human race.”

García Márquez began to hate such elevated praise. It raised expectations he felt he couldn’t fulfill after the enormous success of that incredibly brilliant, seemingly sui generis second novel. Everyone in South America read the book. To avoid the crowds, the author moved to Spain (where Mario Vargas Llosa wrote a doctoral dissertation on him). He needn’t have worried.

Everything he wrote afterward met with near-universal acclaim—bringing earlier work like No One Writes to the Colonel, Leaf Storm, short story collections like A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings, and decades of journalism and non-fiction writing—to a much wider readership than he’d ever had before.

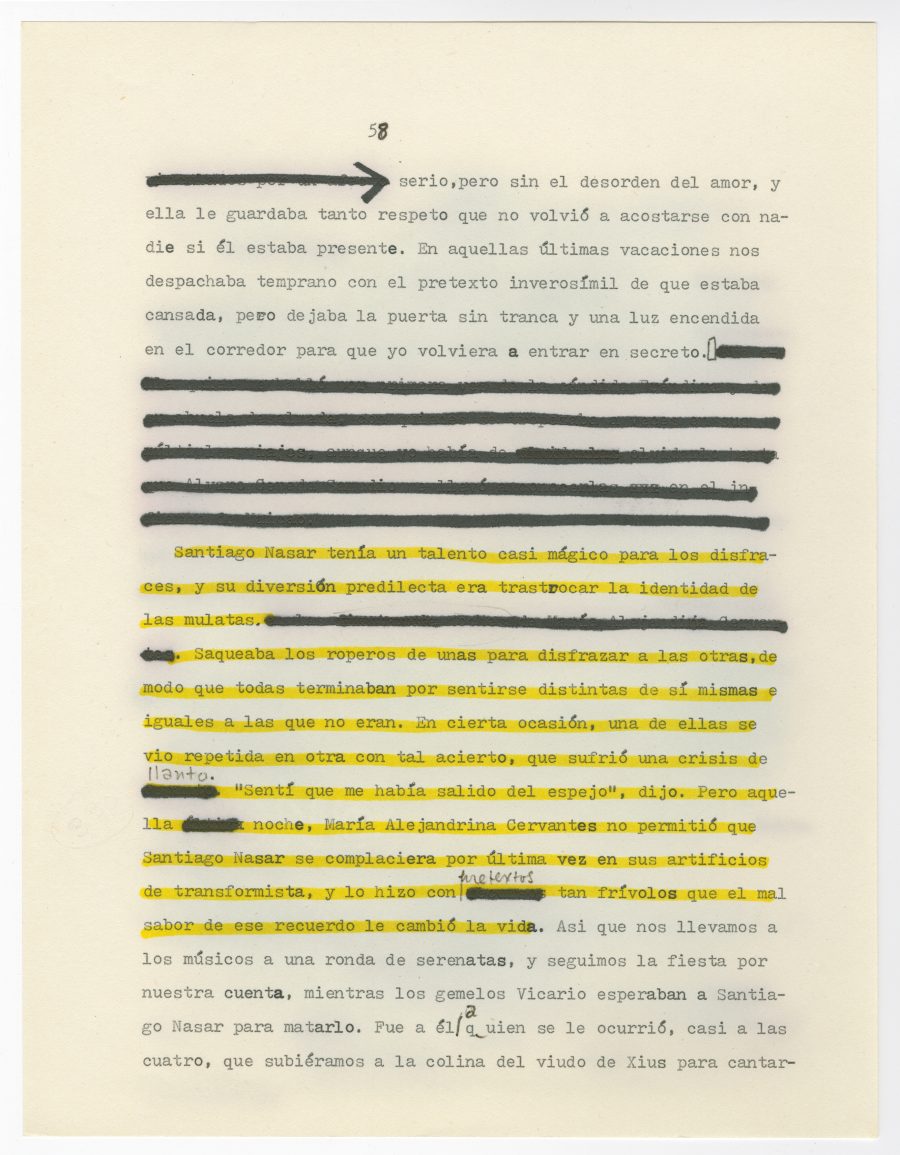

Gabriel García Márquez’s revised typescript of Chronicle of a Death Foretold, 1980.

Courtesy Harry Ransom Center.

After Gregory Rabassa’s 1970 translation of One Hundred Years of Solitude, waves of “magical realist” and Latin American literature from the 50s and 60s swept through the English-speaking world, much of it in translation for the first time. García Márquez declared the English version of his novel better than the original, and affectionately called Rabassa, “the best Latin American writer in the English language.” Upwards of 50 million people worldwide now know the story of the Buendía family. “Published in 44 languages,” The Atlantic notes, “it remains the most translated literary work in Spanish after Don Quixote, and a survey among international writers ranks it as the novel that has most shaped world literature over the past three decades.”

The story of the book’s composition is even more fascinating. In the Democracy Now tribute video below, you can hear García Márquez himself tell it. And at the University of Texas at Austin’s Harry Ransom Center, we can see artifacts like the photograph of the author at the top, in his hometown of Aracataca, Colombia in March of 1966, during the composition of One Hundred Years of Solitude. We can see scanned images of typescript like the page above from Chronicle of a Death Foretold.

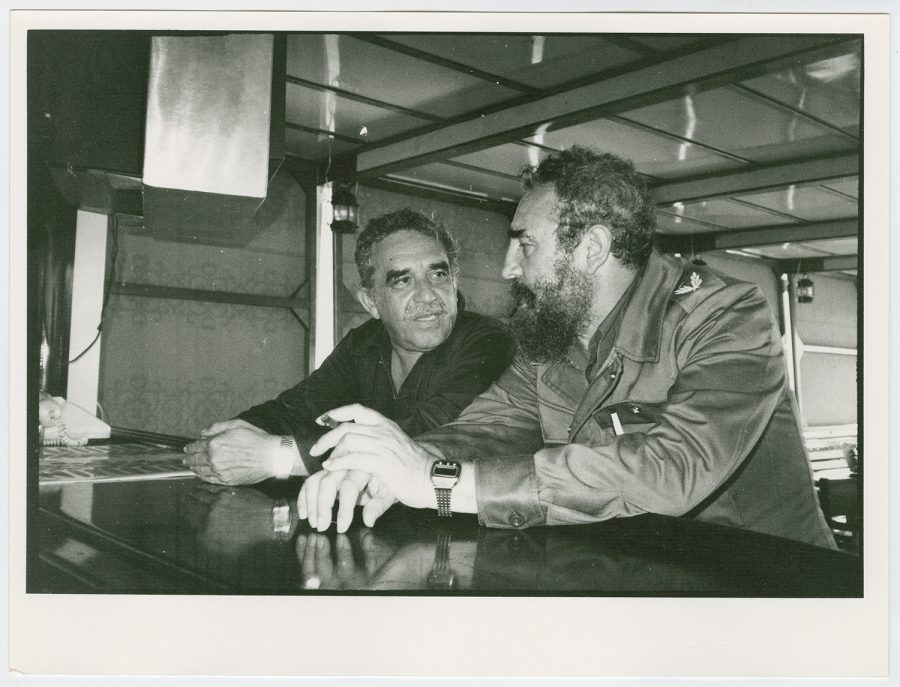

In all, the archive “includes manuscript drafts of published and unpublished works, research material, photographs, scrapbooks, correspondence, clippings, notebooks, screenplays, printed material, ephemera, and an audio recording of García Márquez’s acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1982… approximately 27,500 items from García Márquez’s papers.” These documents and photos, like that further down of young journalist García Márquez with Emma Castro and, just below, of the seasoned famous novelist, with her brother, tell the story of a writer who lived his life steeped in the politics and history of Latin America, and who translated those stories faithfully for the rest of the world.

Unidentified photographer. Gabriel García Márquez with Fidel Castro, undated.

Courtesy Harry Ransom Center.

Enter, search, and explore the archive here. This amazing resource opens up to the general public a wealth of material previously only available to scholars and librarians. The project features “text-searchable English- and Spanish-language materials, took 18 months and involved the efforts of librarians, archivists, students, technology staff members and conservators.” Perhaps only coincidentally, 18 months is the time it took García Márquez to write One Hundred Years of Solitude, barricaded in his office while he ran out of money, pulled forward by some irresistible force. “I did not stop writing for a single day for 18 straight months, until I finished the book,” he tells us. As always, we believe him.

Unidentified photographer. Gabriel García Márquez with Emma Castro, 1957.

Courtesy Harry Ransom Center.

Related Content:

Read 10 Short Stories by Gabriel García Márquez Free Online (Plus More Essays & Interviews)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply