If you follow the ongoing beef many popular scientists have with philosophy, you’d be forgiven for thinking the two disciplines have nothing to say to each other. That’s a sadly false impression, though they have become almost entirely separate professional institutions. But during the first, say, 200 years of modern science, scientists were “natural philosophers”—often as well versed in logic, metaphysics, or theology as they were in mathematics and taxonomies. And most of them were artists too of one kind or another. Scientists had to learn to draw in order to illustrate their findings before mass-produced photography and computer imaging could do it for them. Many scientists have been fine artists indeed, rivaling the greats, and they’ve made very fine musicians as well.

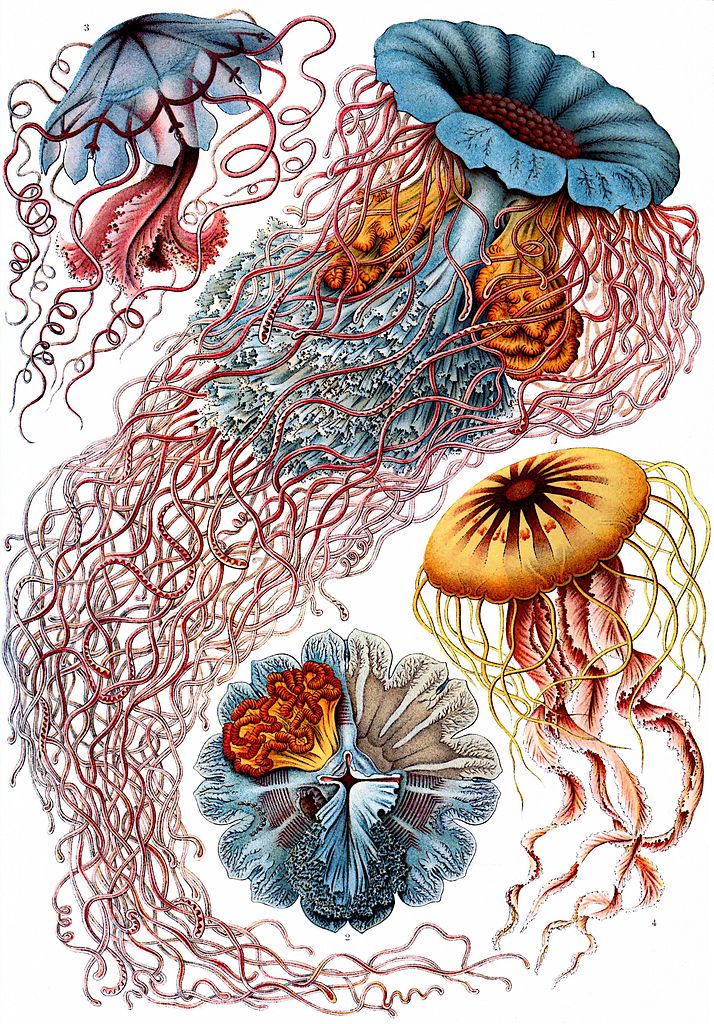

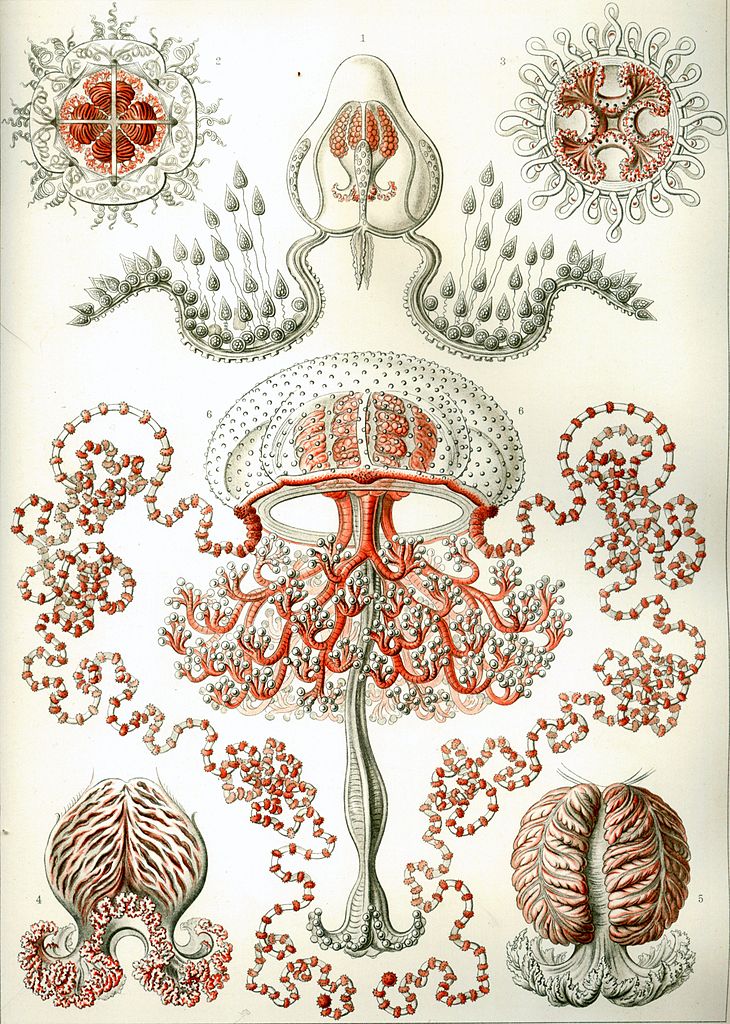

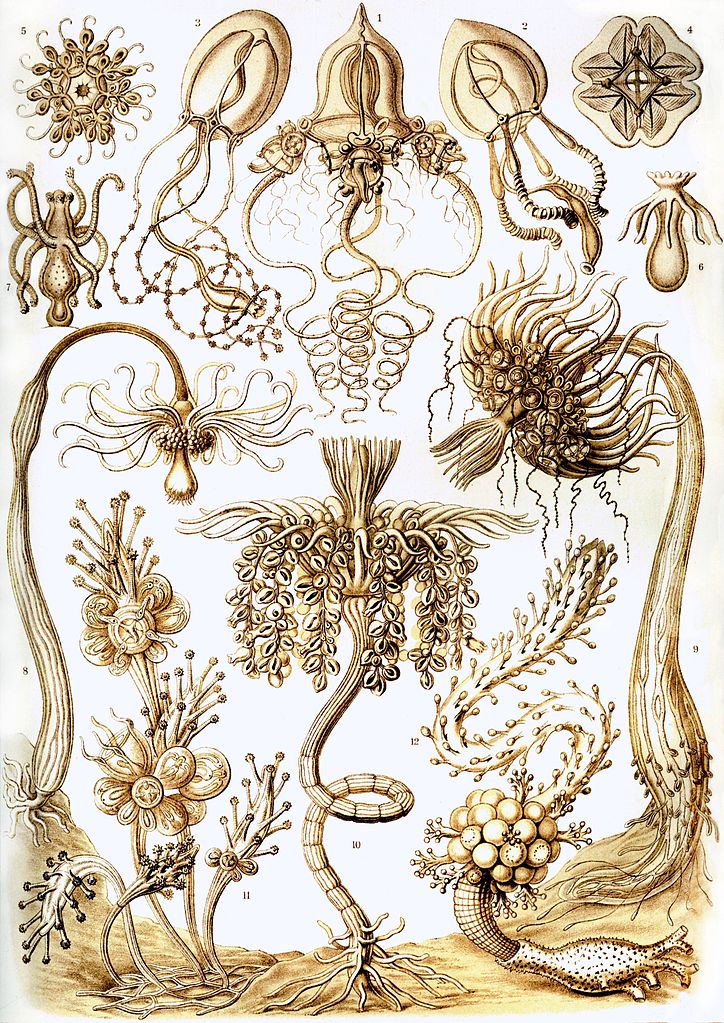

And then there’s Ernst Heinrich Haeckel, a German biologist and naturalist, philosopher and physician, and proponent of Darwinism who described and named thousands of species, mapped them on a genealogical tree, and “coined several scientific terms commonly known today,” This is Colossal writes, “such as ecology, phylum, and stem cell.” That’s an impressive resume, isn’t it? Oh, and check out his art—his brilliantly colored, elegantly rendered, highly stylized depictions of “far flung flora and fauna,” of microbes and natural patterns, in designs that inspired the Art Nouveau movement. “Each organism Haeckel drew has an almost abstract form,” notes Katherine Schwab at Fast Co. Design, “as if it’s a whimsical fantasy he dreamed up rather than a real creature he examined under a microscope. His drawings of sponges reveal their intensely geometric structure—they look architectural, like feats of engineering.”

Haeckel published 100 fabulous prints beginning in 1889 in a series of ten books called Kunstformen der Natur (“Art Forms in Nature”), collected in two volumes in 1904. The astonishing work was “not just a book of illustrations but also the summation of his view of the world,” one which embraced the new science of Darwinian evolution wholeheartedly, writes scholar Olaf Breidbach in his 2006 Visions of Nature.

Haeckel’s method was a holistic one, in which art, science, and philosophy were complementary approaches to the same subject. He “sought to secure the attention of those with an interest in the beauties of nature,” writes professor of zoology Rainer Willmann in a new book from Taschen called The Art and Science of Ernst Haeckel, “and to emphasize, through this rare instance of the interplay of science and aesthetics, the proximity of these two realms.”

The gorgeous Taschen book includes 450 of Haeckel’s drawings, watercolors, and sketches, spread across 704 pages, and it’s expensive. But you can see all 100 of Haeckel’s originally published prints in zoomable high-resolution scans here. Or purchase a one-volume reprint of the original Art Forms in Nature, with its 100 glorious prints, through this Dover publication, which describes Haeckel’s art as “having caused the acceptance of Darwinism in Europe…. Today, although no one is greatly interested in Haeckel the biologist-philosopher, his work is increasingly prized for something he himself would probably have considered secondary.” It’s a shame his scientific legacy lies neglected, if that’s so, but it surely lives on through his art, which may be just as needed now to illustrate the wonders of evolutionary biology and the natural world as it was in Haeckel’s time.

Related Content:

Two Million Wondrous Nature Illustrations Put Online by The Biodiversity Heritage Library

16,000 Pages of Charles Darwin’s Writing on Evolution Now Digitized and Available Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

In the Netherlands, especially in Amsterdam, 3 young architects who founded the Amsterdam School architectural style (1910- 1930 give or take) Designed the beautiful Schipping House (today the 5 star Amrath grand hotel Amsterdam).Joan van der Mey, Michel de Klerk and Piet Kramer. A luxuries office building for six shipping companies in Amsterdam, it was build between 1913–1916 and 1926–1928, overall costs around 35 million guilders.…My grandfather Piet Kramer was one of the architects, and for inspiration he brought along his copy of Kunstformen der Natur by Ernst Haeckel (“Art Forms in Nature”).…many of the drawings were used as inspiration for textile wall coverings, wood carvings and most impressive stained glass all over the building…When in Amsterdam one can book a tour in this monumental building via the Amrath.…given by me by the way :)

kind regards Annebelle Kramer

Thank you, Annabelle — next time! What a splendid thing for you to do. Greetings from London — Jim McCue

Dear Annabelle,

Thanks for sharing all this with us! We will be in Amsterdam for 10 days in July, 2020. Our grandson will be going to the Amsterdam Film School for a week course and I think we would all love this. Is this tour still available?

Best,

Carrell Ebert

I bought a Dover publication of some of these prints back in the late 1960s—and there read that Haeckel did rough drawings of his scientific observations—then handed them over to an un-named Art Nouveau professional artist—perhaps more than one–to tweak the drawings to the degree of finish we now admire—he was the scientist behind the artwork which he then published. Have I been mistaken in my understanding all these years? This understanding caused me to feel free to use his prints as inspiration for works I then did in clay—feeling free to allow my imagination the kind or rein that the Artists he hired obviously used.

Haeckel also promoted eugenics and social darwinism, he was on the Jury of the Krupp family’s price awarding possible approaches of applying Darwinism to German law. He was a race theoretician, it’s easy to google. People are complex, I say it’s a blessing that part of his scientific work lies neglected and it should very much stay that way.