It is for good reason that we forever associate illustrator Ralph Steadman with the delirious work of Hunter S. Thompson. It took the two of them together to invent the gonzo style of journalism, which we may almost call incomplete now if published without the requisite cartoon grotesques. Steadman conjures visions of devils and demons as deftly as any medieval church painter, but his hells remain above ground and are mostly man-made. Whether illustrating Ambrose Bierce’s Devil’s Dictionary, George Orwell’s Animal Farm, the cast of Breaking Bad, or the visages of American presidents, he excels at showing us the freakish fever dreams of the modern world. He may, wrote The New York Times’ Sherwin Smith in 1983, “be the most savage political cartoonist of the late 20th century.”

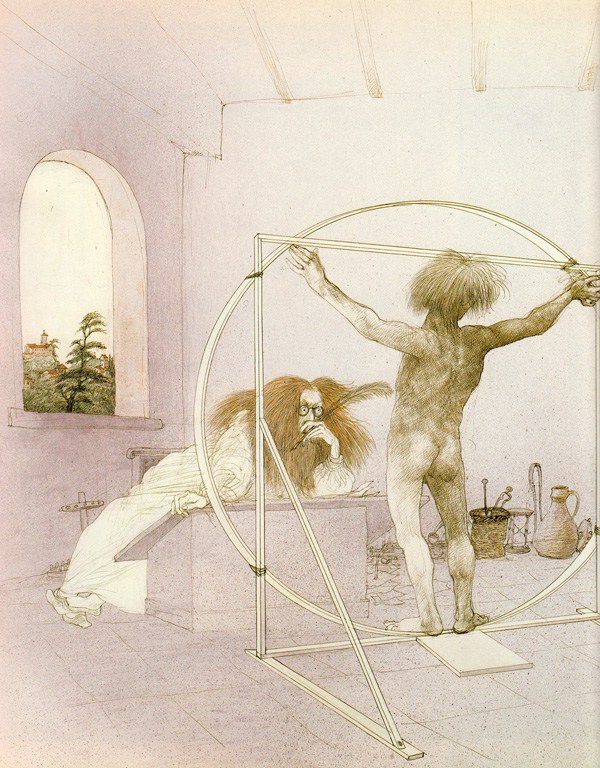

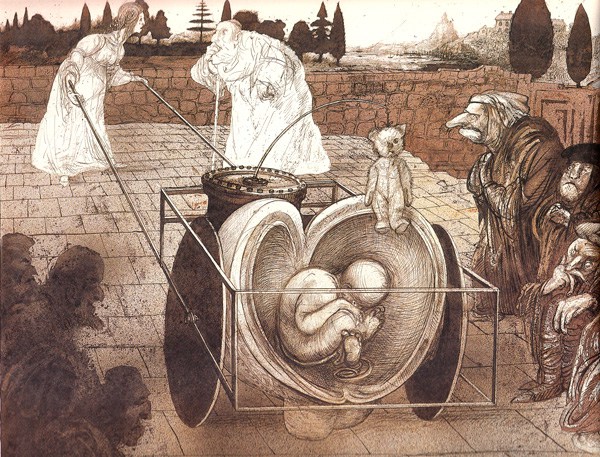

Steadman’s illustrative legacy places him in the company of history’s greatest visual satirists, but also makes him an odd choice for a biography of Leonardo da Vinci. Though Leonardo frequently drew caricatures in his notebooks, the bulk of the Renaissance genius’s work concerns itself with order and precision—the purposefulness of his line a stark contrast to the crazed ink splatters of Steadman’s work.

Nonetheless, Steadman’s I, Leonardo, which he undertook not on commission but on his own initiative, exhibits a profound insight into the Italian painter-sculptor-philosopher-inventor’s restless creative mind. Leonardo presented a very cool exterior, but his inner life may well have resembled a Steadman drawing.

The project came to life in 1983 as what Steadman called “a quasi-historical mishmash,” a “tongue-in-cheek” supposed long-lost autobiography of Leonardo in pictures. “It is more than a collection of illustrations on Leonardo’s life, based upon three years of work and research,” remarked a Washington Post review. “Steadman does not merely theorize about the man, but attempts to go inside the artist’s bones.” Steadman, writes Maria Popova, “even travelled to Italy to stand where Leonardo stood, seeking to envision what it was like to inhabit that endlessly imaginative mind.” The illustrations are a surprisingly effective combination of da Vinci-esque discipline and Steadmanesque sick humor.

In his introduction to the book, Steadman comments on Leonardo’s split persona. His “experience showed him that man was not what he appeared to be, despite the prevailing atmosphere of fine thoughts and high aspirations…. The purity of his painting set the divine standard of Renaissance art—and of any art for that matter. I believe he preserved intact a part of his private self which found outlet in his more personal notes and drawings.” Many of those drawings include the aforementioned caricatures of monstrous, grimacing beings who would fit right in with Steadman’s nightmarish drawings.

The gonzo illustrator found a kindred satirical Leonardo inside the famed master draughtsman and engineer. His interest in the Renaissance artist’s anarchic psyche mirrors that of another keen observer, Sigmund Freud, who described Leonardo as “a man who awoke too early in the darkness, while the others were all still asleep.” (Steadman’s first “historical mishmash” project was a 1979 illustrated Freud biography.) The artist behind I, Leonardo has a slightly different take on the subject. Steadman, writes Smith, saw Leonardo “in 1980’s terms—as ‘a man taken up by a corporation that couldn’t use him.’”

See many more of Steadman’s Leonardo illustrations at Brain Pickings and purchase a copy of the book here.

Related Content:

Ralph Steadman’s Surrealist Illustrations of George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1995)

Gonzo Illustrator Ralph Steadman Draws the American Presidents, from Nixon to Trump

Breaking Bad Illustrated by Gonzo Artist Ralph Steadman

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply