The word “nativist” always sounds odd to me given that most of those to whom it applies descend from people who arrived in North America one or two hundred years ago to find people who had been on the continent for many thousands of years. But if we were, in defiance of history, to confer native status upon the many waves of European immigrants who populated the country before and after the Civil War, then we must also grant such status to the many Chinese immigrants who did so, building railroads and businesses all over the U.S., including on the western frontier in Mississippi.

Chinese immigrants first arrived in the Mississippi Delta after the end of slavery, responding to cotton planters’ need for a newly exploitable workforce. Chinese laborers, says the narrator in the Al Jazeera video above, “were cheap, disposable, and politically voiceless.” But they were, at least, paid for their work, and free to leave it, as most of them did when they could, to build their own economic means—largely businesses “serving the black community when the white community wouldn’t.” In an NPR profile of the Delta Chinese community, Melissa Block interviewed Raymond Wong, whose family arrived somewhat later, in the 1930s. “We were in-between,” he tells her, “We’re not black, we’re not white. So that by itself gives you some isolation.”

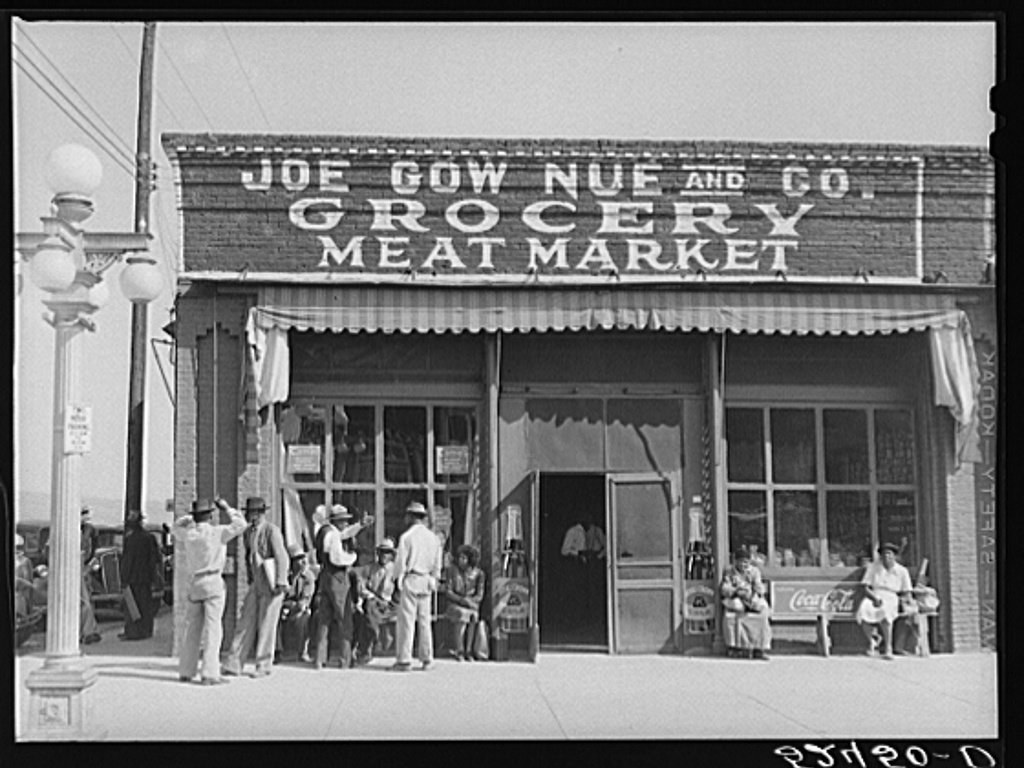

Photo by Marion Post Wolcott/Library of Congress

That in-between-ness also grants a good deal of invisibility to communities that don’t fit into the binary patterns of thinking in Southern culture and history or the oversimplifications of U.S. demographic history in general. As historian David Reimers demonstrates in his book Other Immigrants, in addition to native Amerindians, Europeans, and enslaved African people, the country has been inhabited by free Black, Caribbean, Asian, and Latin American communities since the 16th century and up to, and after, the harsh exclusion acts of the 19th century. The U.S. would not be recognizable without such communities. As far back as the eighteenth century, he writes, “Pennsylvania and New York City, with their ethnically diverse populations, became models for the American future, a pluralist society.”

In the South, non-European immigrant communities have been smaller minorities, like the Delta Chinese. Nonetheless, as Mississippi resident Frieda Quon recalls of growing up in segregated Mississippi, the Chinese immigrants who settled from Memphis to Vicksburg “really filled a particular need”—first for labor then for services—“because nobody else wanted to do it.” Even after the community endured many years of bigotry and legal discrimination during the exclusion acts, several men distinguished themselves among the 13,000 Chinese Americans who served in the U.S. armed forces during World War II.

The 10-minute trailer above for Honor and Duty, a three part documentary series about the Mississippi Delta Chinese community, begins with a brief profile of the almost two hundred Chinese American soldiers, marines, sailors, and airmen from the region. Director E. Samantha Cheng made the film as part of her larger mission to tell Asian-American history, which few Americans of any descent know very much about. In fact, she took on her mission after recovering from the shock of learning as an adult about the U.S.‘s Japanese internment camps during the war, something she had never been taught in New York City public schools.

Cheng was surprised during her filming to meet so many Chinese-Americans with molasses-thick Southern accents. “Even their Chinese accent has a Southern twang to it,” she tells NBC. That’s because, though accent alone does not a “native” make, the Chinese communities in the Mississippi Delta are, as much as anyone else in the region, Southerners.

The AJ video is part of a series on 150 years of Chinese culture and cuisine in the U.S. See Part One, on San Francisco, here, and the Part Two, covers Los Angeles, here.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply