Art Nouveau, Art Deco… these are terms we associate not only with a particular period in history—the turn of the 20th century and the ensuing jazz-age of the 20s—but also with particular locales: Paris, New York, L.A., London, Vienna, or the Jugendstil of Weimar Munich. We probably do not think of Rio de Janeiro. This may be due to biases about the privileged location of culture, such that most people in Europe and North America, even those with an arts education, know very little about art from “the colonies.”

But it is also the case that Brazil had its own modern art movement, one that strove for a distinctly Brazilian sensibility even as it remained in dialogue with Europe and the U.S. The movement announced itself in 1922, the centennial of the South American nation’s independence from Portugal.

In celebration, artists from São Paulo held the Semana de Arte Moderna, seven days in which, the BBC writes, they “constructed, deconstructed, performed, sculpted, gave lectures, read poetry and created some of the most avant-garde works ever seen in Brazil.”

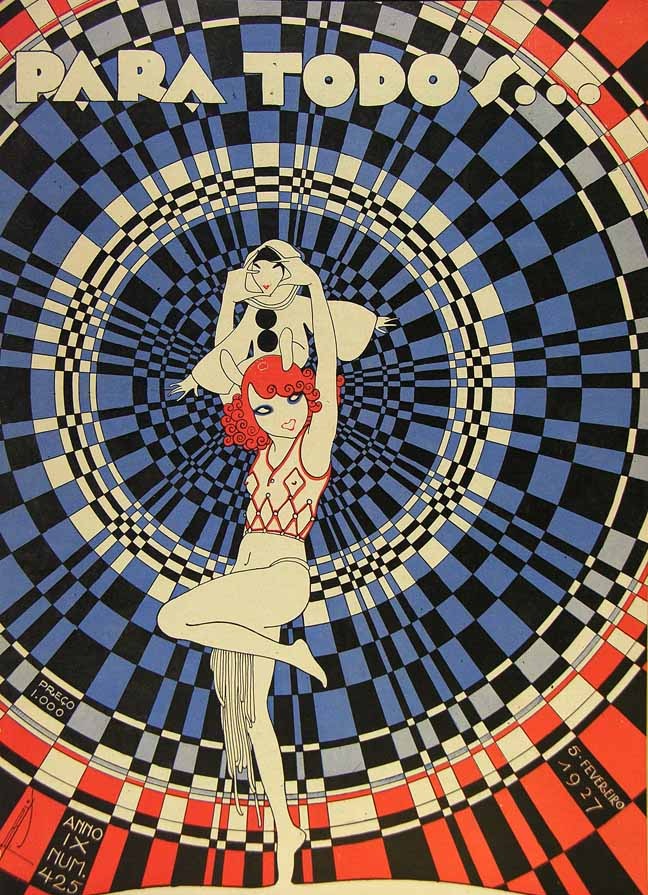

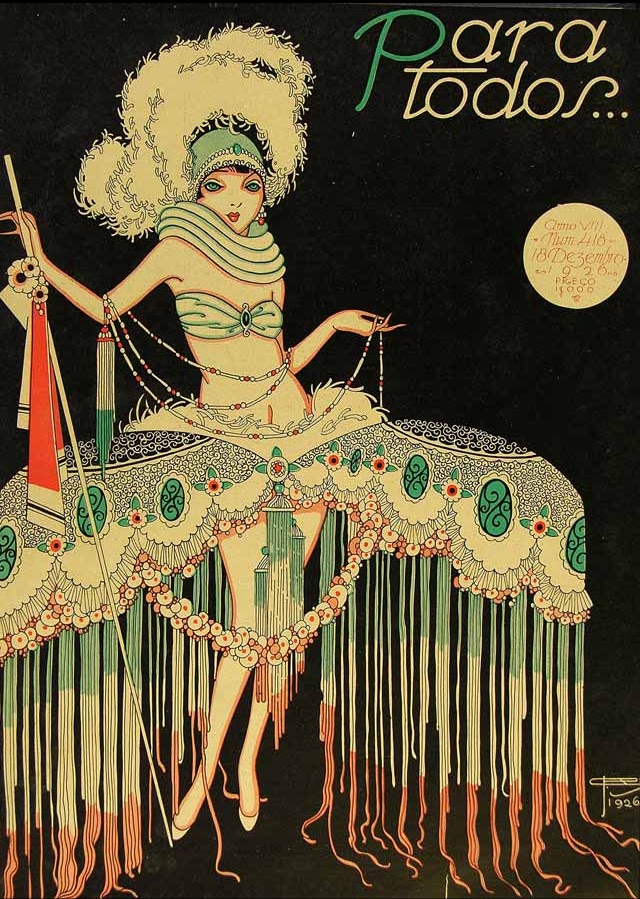

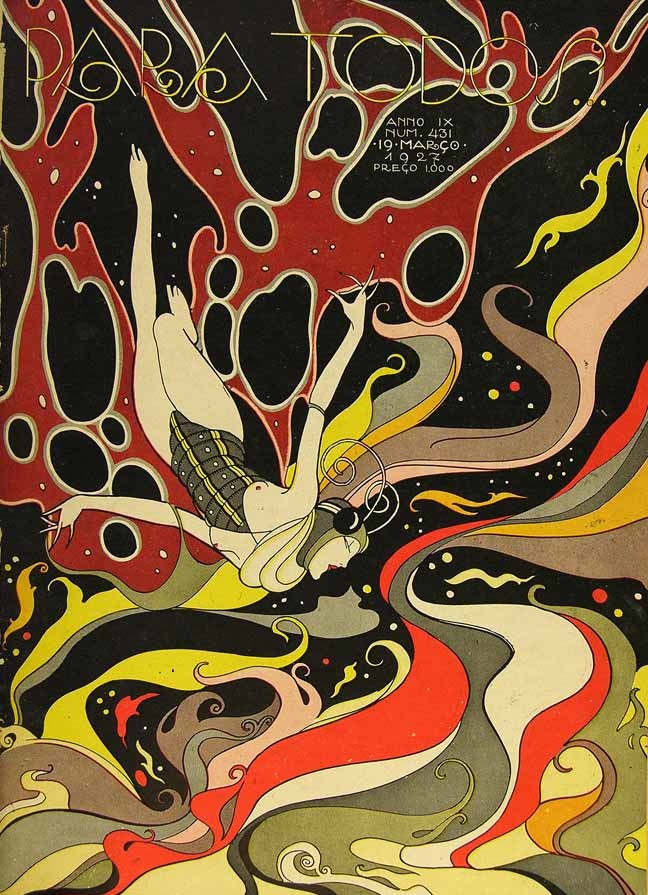

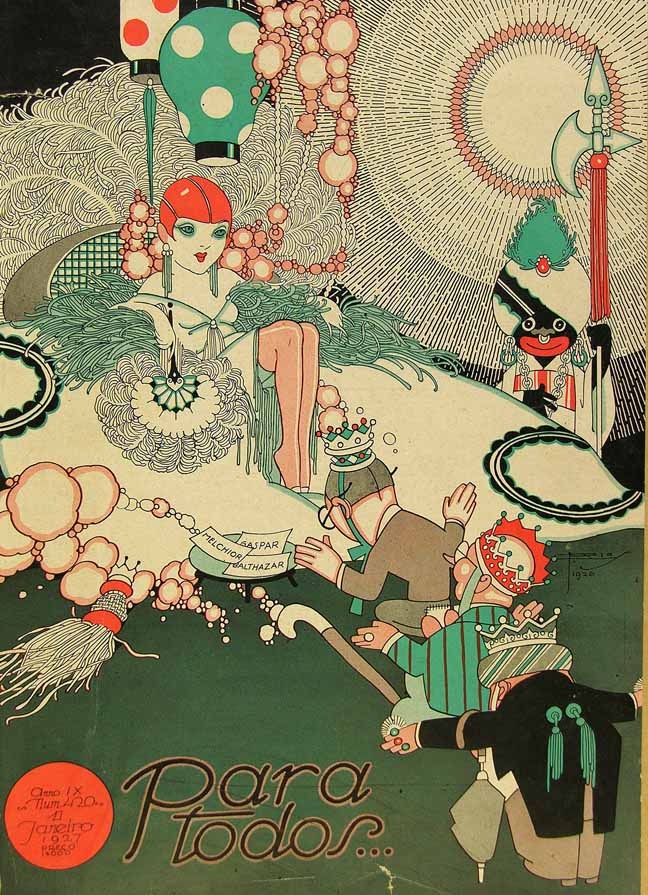

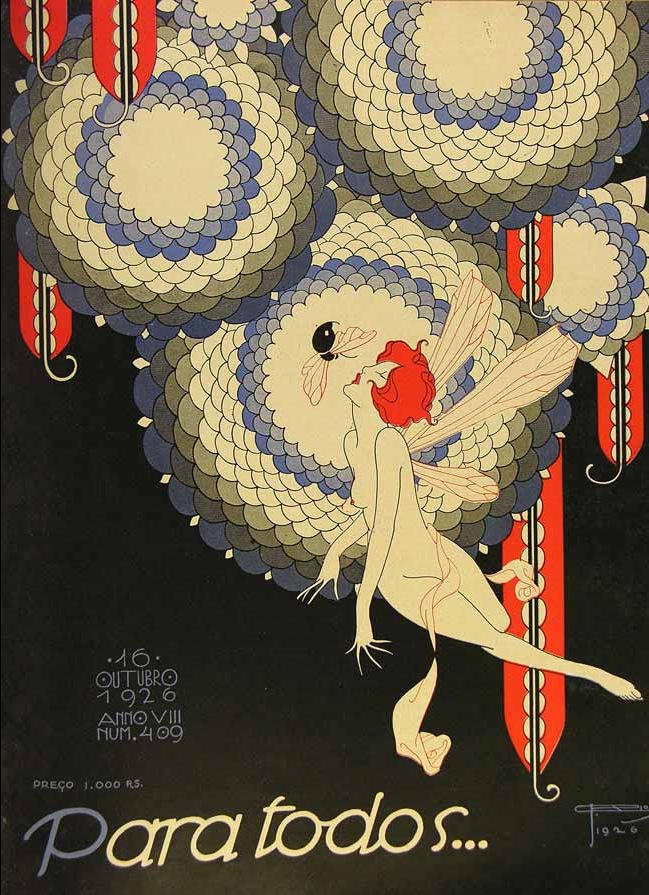

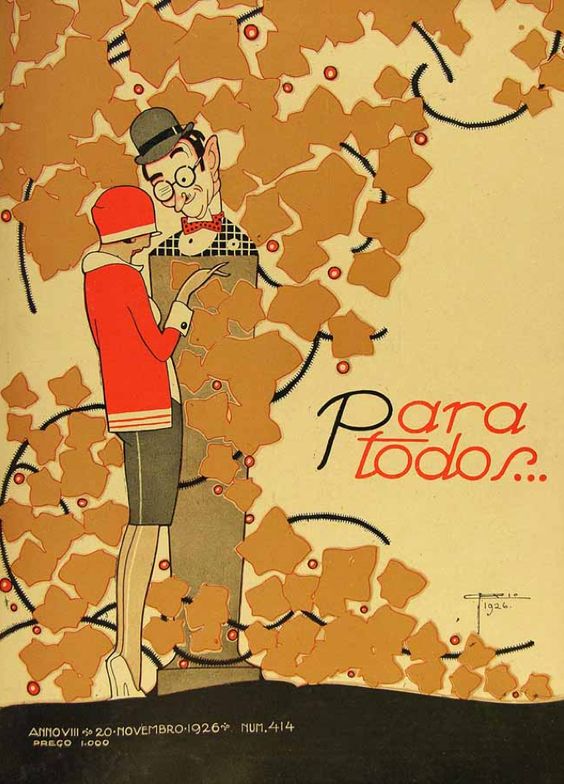

1922 also happened to be the year that a Rio de Janeiro-born artist, illustrator, and graphic designer who went by the name J. Carlos (José Carlos de Brito e Cunha) took over the direction of the magazine Para Todos. Founded in 1918, the magazine began as a film rag, and its covers faithfully featured photo spreads of movie stars. But in 1926, Carlos, who had already proven himself a “major talent in Brazilian Art Deco graphic design,” writes Messy Nessy, began drawing his own cover illustrations, and he continued to do so for the next four years, as well as drawing thousands of cartoons and writing vaudeville plays and samba lyrics.

His work clearly draws from Euro-American sources, including several unfortunate racial caricatures. But it also introduces some uniquely Brazilian elements, or uniquely Carlos-ian elements, that seem almost proto-psychedelic (we might imagine a jazz-age Os Mutantes accompanying these trippy designs). J. Carlos was a prolific artist who “collaborated in design and illustration in all the major publications of Brazil from the 1920s until the 1950s.” In all, it’s estimated that he left behind over 100,000 illustrations. So devoted was Carlos to the art and culture of his native city that he apparently turned down an invitation by Walt Disney to work in Hollywood.

Print magazine describes Carlos’ work as “a cross between Aubrey Beardsley and John Held Jr.,” and while there is no shortage of the willowy, doll-like flappers, elongated, elfin figures, and intricate, spidery patterns we would expect from this derivation, Carlos is also doing something very different from either of those artists—or really from anyone working in the Northern Hemisphere. He has since become a heroic figure for Brazilian artists and scholars, inspiring an extensive web project, a visual thesis on Issuu, and two recent documentary films (all in Portuguese), which you can find here.

In 2009, Carlos received a posthumous honor that probably would have thrilled him in life, a tribute song by the Académicos da Rocinha samba club. Listen to it here and find several more of Carlos’ Para Todos covers at Messy Nessy, Print, and the Brazilian blog Os caminhos do Journalismo.

Related Content:

Download Hundreds of Issues of Jugend, Germany’s Pioneering Art Nouveau Magazine (1896–1940)

Harry Clarke’s 1926 Illustrations of Goethe’s Faust: Art That Inspired the Psychedelic 60s

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Enjoyed the article. Please observe the correct spelling of South America’s largest city in future: São Paulo.

Ciao 😎

Corrected, thank you!

JCarlos was pretty ahead of his time!

Very interesting text! I would like to add that many buildings in Rio and São Paulo were projected in Art Deco style, too.

Just discovered J. Carlos, aka José Carlos de Brito e Cunha, this week. As a lifelong art deco fan, I can’t get enough.