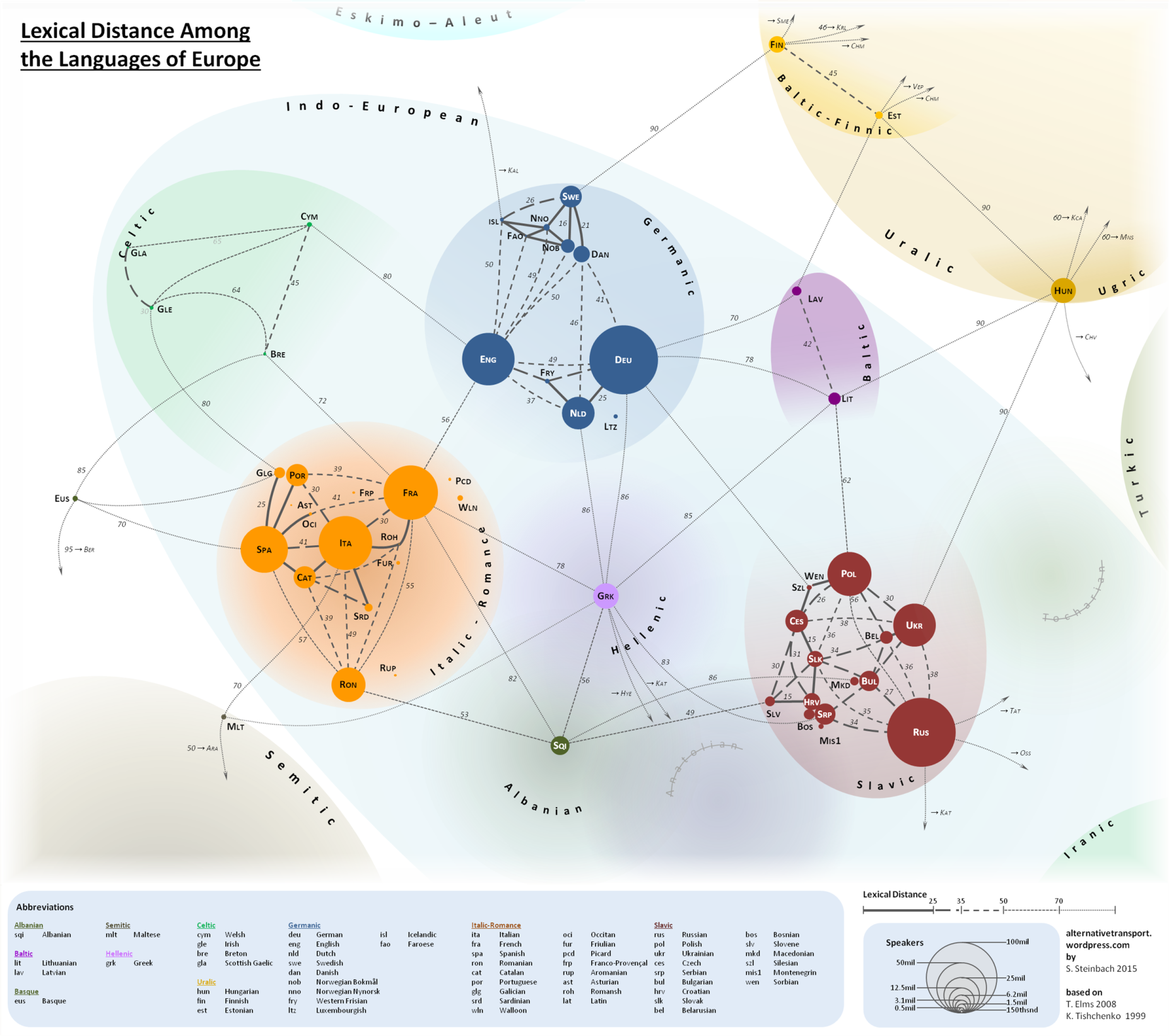

Stephen F. Steinbach, a resident of Vienna and a “cartography, language and travel enthusiast, with an engineering background,” is not a linguist. Steinbach, who runs the site Alternative Transport, seems much more interested in mapping and transportation than morphology and etymology. But he has made a contribution to a linguistic concept called “lexical difference” with the map you see above, a colorful 2015 visualization of European languages, grouped together in clusters according to their subfamilies (Italic-Romance, Baltic, Slavic, Germanic, etc.—see a much larger version here).

Straight and arcing lines span the relative distance these languages have presumably traveled from each other. Solid lines between languages represent a very close proximity, dashed lines of different thicknesses show more distance, and thin dotted lines traverse the greatest expanses.

Hungarian and Ukrainian, for example, have a lexical distance score of 90, where Polish and Ukrainian, both Slavic languages, are only 30 degrees from each other. “The map shows the language families that cover the continent,” writes Big Think, “large, familiar ones like Germanic, Italic-Romance and Slavic, smaller ones like Celtic, Baltic and Uralic; outliers like Semitic and Turkic; and isolates—orphan languages, without a family: Albanian and Greek.” (Technically, modern Greek does have a family—Hellenic—though it is the only surviving member.)

As we might expect from this subset of the durable Indo-European schema, the languages within each clustered group occupy the shortest distance from each other, with some exceptions. Romanian, for example, is slightly closer to Albanian than it is to French, its Romance cousin. The Slavic languages Russian and Polish seem to have traveled a bit further apart than Polish has from the Baltic language of Lithuanian. What does this mean, exactly? According to the measure of “lexical distance” proposed by Ukrainian linguist Konstantin Tishchenko, it means that closer languages might be more mutually intelligible, at least from a lexical standpoint, since they may share more cognates (similar-sounding and meaning words) and borrowings.

Gaston Ümlaut, the handle of a linguist on the Stack Exchange Linguistics beta, cautions that the concept of “lexical distance” may be “pretty useless” given that the comparisons also include false cognates—words that sound or look similar but have no relationship to each other. These could account for some seeming inconsistencies. (Ümlaut admits he has not read the original article, written in Russian. If you are able, you can find it online in the book Metatheory of Linguistics, here.) Steinbach has responded in the same thread.

The idea received a much more trenchant critique more recently. Steinbach clarified that the theory, and the map, only compare written words and not syntax or speech. “It has nothing to do with grammar, syntax, rhythm or other important features that are important for intelligibility,” he writes. “It also compares a small list of words and not the entire vocabulary of one language to another.” This explanation does cast doubt on whether “lexical distance” is a meaningful concept. I’ll leave it to the linguists to decide. (Steinbach reached out to Tischchenko but has yet to receive a reply.)

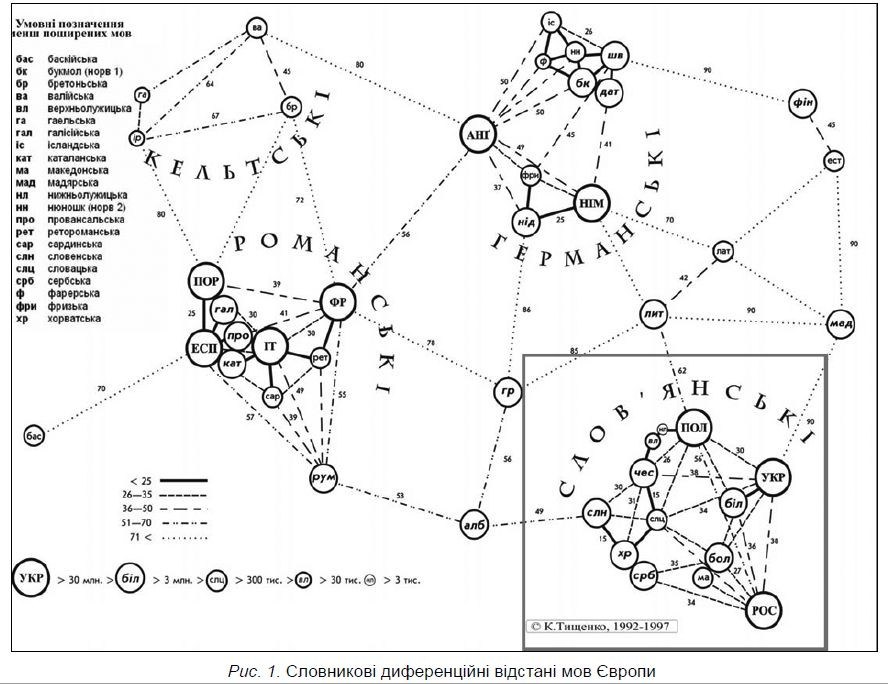

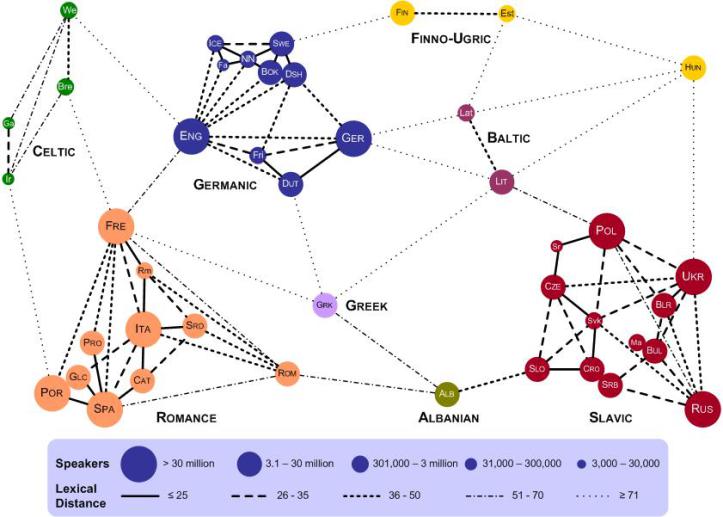

Tischchenko’s original “lexical distance” map, further up, drawn in 1997, gets the idea across with minimal fuss, but it leaves much to be desired graphically. (A large, hand-drawn color version improves upon the printed map.) Steinbach took his version from a 2008 English-language adaptation made by Teresa Elms in 2008 (above). In his blog post here, he explains all of the changes he made to Elms and Tischchenko’s designs. These include adjusting the size of the “bubbles” to proportionally represent the number of speakers of each language. Steinbach also added several languages, as well as “gravestones” for the dead Anatolian and Tocharian branches. In all, his map shows “54 languages, representing 670 million people.” He adds, vaguely, that “it checks out.”

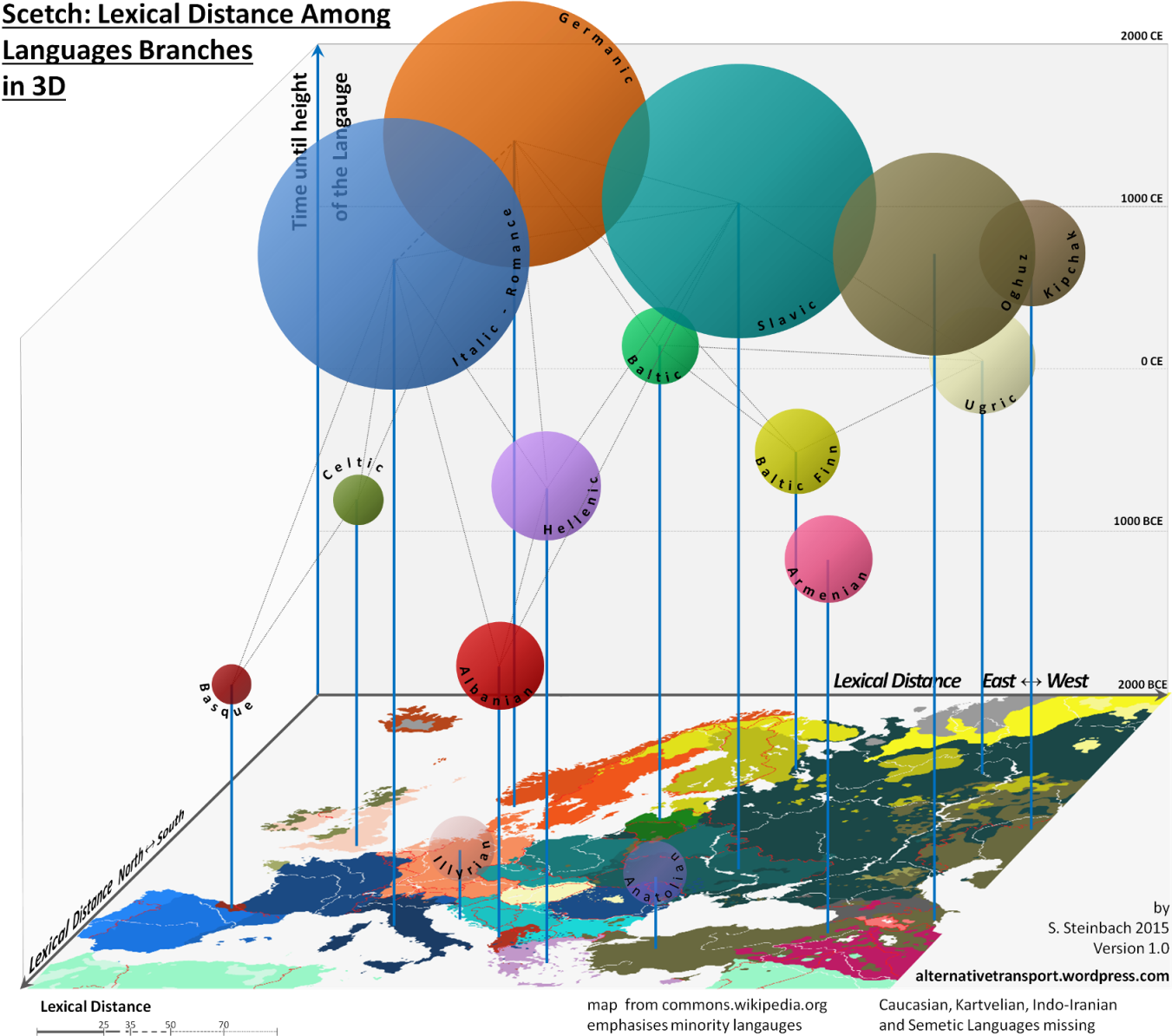

After posting his Lexical Distance Map, Steinbach proposed a “3D” version, with the added dimension of time. (See his preliminary sketch above.) The maps are intriguing, the theory of “lexical distance” an interesting one, but we should bear in mind, as Steinbach writes, that he is “no linguist,” and that this idea is hardly an orthodox one within the discipline.

via Big Think

Related Content:

The Tree of Languages Illustrated in a Big, Beautiful Infographic

How Languages Evolve: Explained in a Winning TED-Ed Animation

Speaking in Whistles: The Whistled Language of Oaxaca, Mexico

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

I’ll throw in the fact that Scottish Gaelic and Irish Gaelic are not the same language. All of the Irish speakers in my Scottish Gaelic classes do not think it is the same.

The only one issue is that Konstantin Tishchenko is Ukrainian linguist, not Russian. Even the screenshot of the book page with the map in this article is from the Ukrainian book

Corrected, thank you.

The map should include Iranian and Indian languages (at least northen part), maybe ancient and modern. The language group is “Indo-European”. It seems to me that lexical distance between Slavic and Indo-aryan languages might be smaller than between Slavic and Romance or German languages.

Scottish and Irish Gaelic are closely related. I can follow much of Scottish Gaelic on TV even though my Irish Gaeilge is rusty. Irish Gaelic as spoken in Donegal is certainly much closer to Scottish Gaelic than to Gaelic spoken in West or South of Ireland. ‘Same language’ is a very relative term. Strict languages were codified by nation-states’ national academies and central governments. But it seems clear to me that among Celtic languages, there are common elements between Scottish and Irish Gaelic and between Breton and Welsh. Breton or Welsh speakers find learning the other language of this pair much easier than tackling Gaelic.

Metatheory of Linguistics is written in Ukrainian, not Russian. And the name of linguist is Kostiantyn Tyshchenko, not Konstantin Tishchenko, because Konstantin is a Russian name, not Ukrainian.

There is monumental disconnect in the western world with respect to historical origin of the names Rus’(~Ukraine), Russia, Grand Tartaria, Hord, or what they represent. The aforementioned eponymous are well know in the post Soviet republics that managed to escape the “Union” and there is almost universal agreement among them about real history and the nature of Kremlins pseudo-history that it uses as a weapon of war.

“Russian” is not an organic language, but a forcefully imposed Old-Bulgarian (Second Slavic translation of the Bible*) over all of the subjects that were under Kremlins** control. The original policy was implemented by Peter the Great in ~1700 and the following czars kept up the policy in order to reunify the old territories of the Horde under one “Christian” language. Another reason for specifically adapting a Slavic language, could have been Kremlins plan of expansion into Slavic territories and appropriation of their history/culture. Original languages of Grand Tartaria encompassed almost whole Finno-Uralic family, and to a lesser degree, Turik. Moscow was just one of the centers for collecting tribute which was sent to the Khans in Crimea, Kazan, Astrahan, and Kasimov. This was the case since the time of Genghis Khan and until ~1700. Moscow’s rulers them selves were Turik Khans of lesser rank, however, today only their Christian names are shown in modern history books. Since the Khans in the Horde allowed Christianity to coexist with Islam, it was a common practice for the Khans to have a Christian name to supplement their official name which can be easily seen in Turik records.

Also, at the time of USSR, the distribution of languages could have been altered even more when Kremlin killed off 10s of millions of people (mostly in Ukraine and Khazakstan) and forcefully relocated Uralic people into newly depopulated areas. Furthermore, Kremlin had almost 300 year long effort of destroying the original cultures, writings, and languages of the indigenous people (including Finno-Uralic people of Moscow), in order to achieve a uniform Empire under the new (Old-Bulgarian) language.

All of these factors have to be taken into account by any linguist if he hopes to ever reconstruct the actual linguistic history of PIE. For those that understand Russian, there is a good resource on YouTube channel “История Руси”. English speakers, instead of relying on Kremlins propaganda, can contact actual historians in the Baltic or Slavic states.

*First Slavic translation of the Bible was done in Moravia using Glagolic alphabet, the second translation known as Old-Bulgarian was an adaptation of Glagolic version to new Cyrilic alphabet and the Bulgarian language. It should be noted for linguistic purposes, Bulgarians are Turik people that raided and settled Macedonia/Rus’, later they adapted the surrounding Slavic language.

**Kremlin means Fortress in Turik while Moscow means swamps or dirty water in Finnish.

Where did Putin touch you?

Ukrainian science is strongly influenced by Ukrainian nationalism. The idea fix of Ukrainian nationalism is to prove that Ukraine has nothing to do with Russia. Not surprisingly, in this scheme, published by the Ukrainian researcher Tishchenko, Bulgarian is the closest language to Russian. From the point of view of conventional scientific data, this is absurd.

My native language is Russian. Bulgarian is the same as Chinese for me. I almost do not understand Bulgarian words and do not catch what the conversation is about. When I come across a familiar word, it doesn’t mean what I think. In Ukrainian, I know half of the words and in general I understand spoken language, although I have never lived in Ukraine.

Vladimir I don’t know how come you don’t understand Bulgarian but even I can understand Bulgarian not too bad and it’s mostly because I know Russian and of course other Slavic languages are helpful. Regarding Russians understanding Ukrainian sounds funny. If I had a dime for every single time when I met a Russian who couldn’t understand a word from me speaking Ukrainian and asking to repeat in Russian instead — I would be a millionaire.

Why are ukrainians in general so allergic to the concept of dialect continuum? No languages are homogenous and clearly lexically demarcated, especially if they were within the border of a multinational empire such as the Russian, Ottoman or Austrohungarian empires allowing for increased interaction. Different ukrainian dialects have different lexical distance to Russian. Same as dialect continuums of Langue d’Oil and Langue D’oc, Serbocroatian and Bulgarian, etc. Modern academic ukrainian has a lot more polonisms and slovak cognates compared to many eastern or central varieties of ukrainian, which is normal since, the center of ukrainian nationalism is Galicia.

It’s interesting that a dashed line, implying greater than 25% difference in vocabulary, links Irish and Scottish Gaelic.

Is this because they have slightly different spelling conventions? E.g., Irish for school is scoil but it is spelled sgoil in Scottish Gaelic.

Also, Irish has shortened spelling for many words where Scottish Gaelic retains an un-shortened spelling. E.g., lenition is séimhiú (un-shortened spelling séimhiughadh) in Irish and sèimheachadh in Scottish Gaelic. They’re all the same word with the same meaning but slightly different spellings.

Josh, thanks for this summary. Exactly what I was searching for and it popped up as the second link on Google.

In a addition to a previous comment, please note that your “original article, written in Russian” links to an article in Ukrainian.