Americans swim in propaganda all the time, even those of us who think the word refers to some exotic form of foreign authoritarianism rather than our own good ol’ home-cooked variety. But the sad fact—admittedly very far down the list of rather tragic facts—is that U.S. propaganda is particularly crude, obnoxious, and unappealing. Contrast, for example, the symbol of the pantsuit, or the casual racism, misogyny, and homicidal fantasies on trucker hats, t‑shirts, and beach towels with the alarming pageantry of Maoist China, Stalinist Russia, or name-your-showy-totalitarian-regime.

In the early days of the Soviet Union, state propaganda received a special boost from a cadre of eager and willing avant-garde artists, including poet, actor, director, etc. Vladimir Mayakovsky, who wrote Soviet children’s books, and a number of Russian Futurists who seized the opportunity to promote the new order with totally incomprehensible poetry and art.

In no way regimented or standardized, as were later Socialist Realists, early Soviet propagandists used politics as another material in their work, rather than its primary raison d’être.

These pioneers were joined by experimental composers, filmmakers, and even textile designers, who had a brief moment under the shining Soviet star between 1927 and 1933, when, as one publication from a wealthy collector notes, “a fascinating experiment in textile making took place in the Soviet Union. As the new nation emerged and the Communist party struggled to transform an agrarian country into an industrialized state, a group of young designers began to create thematic textile designs.”

Their designs—adorning tablecloths, sheets, curtains, and scarves and other items of everyday, off-the-rack wear—showcase bold, striking patterns, many, writes Dangerous Minds, “thematic of classical Russian art: you see lush color, dense scapes and even the odd Orientalist trope.” They are also filled with “delightfully propagandist imagery,” notes Marina Galperina at Flavorwire, “of revving tractors, smoke-pumping factor pipes, and babushka-clad women taking a sickle to wheat… woven in between opulent florals and pretty, constructivist squiggles.”

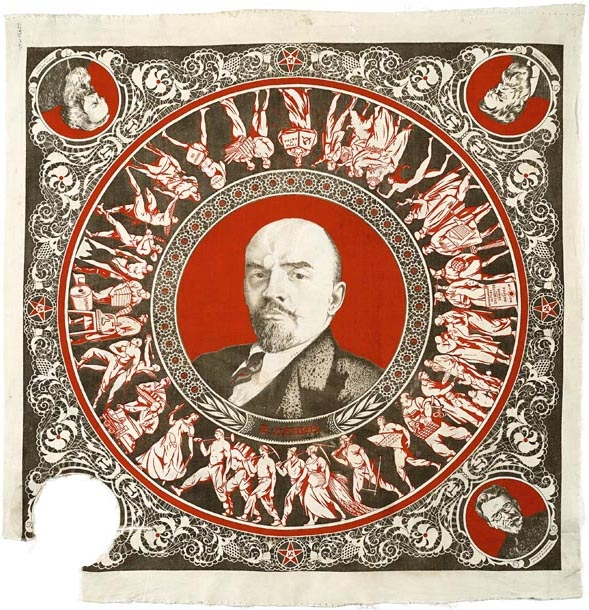

Factory gears, war machines, athletes, and scenes of industry were popular, as were the expected state symbols and iconography—as in the Lenin linen at the top, framed at the top by Marx and Engels; Trotsky at the bottom left has been purged from the textile record. See many more examples of early Soviet textiles at io9, Flashbak, and Messy Nessy.

via English Russia and @TedGioia

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Totalitarian beach towels. Is this what it has come to?