We think of Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press (circa 1440) to have begun the era of the printed book, since his invention allowed for mass production of books on a scale unheard of before. But we must date the invention of printing itself much earlier—nearly 600 years earlier—to the Chinese method of xylography, a form of woodblock printing. Also used in Japan and Korea, this elegant method allowed for the reproduction of hundreds of books from the 9th century to the time of Gutenberg, most of them Buddhist texts created by monks. In the 11th century, writes Elizabeth Palermo at Live Science, a Chinese peasant named Bi Sheng (Pi Sheng) developed the world’s first movable type.” The technology may have also arisen independently in the 14th century Yuan Dynasty and in Korea around the same time.

Despite these innovations, xylography remained the primary method of printing in Asia. The “daunting task” of casting the thousands of characters in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean “may have made woodblocks seem like a more efficient option for printing these languages.” This still-labor-intensive process produced books and illustrations for several centuries, a good many of them incredible works of art in their own right.

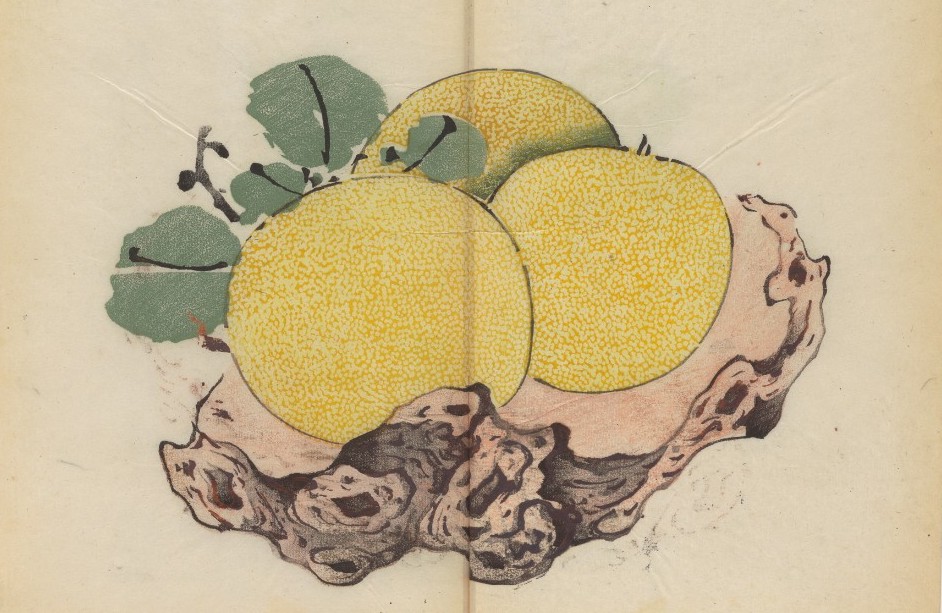

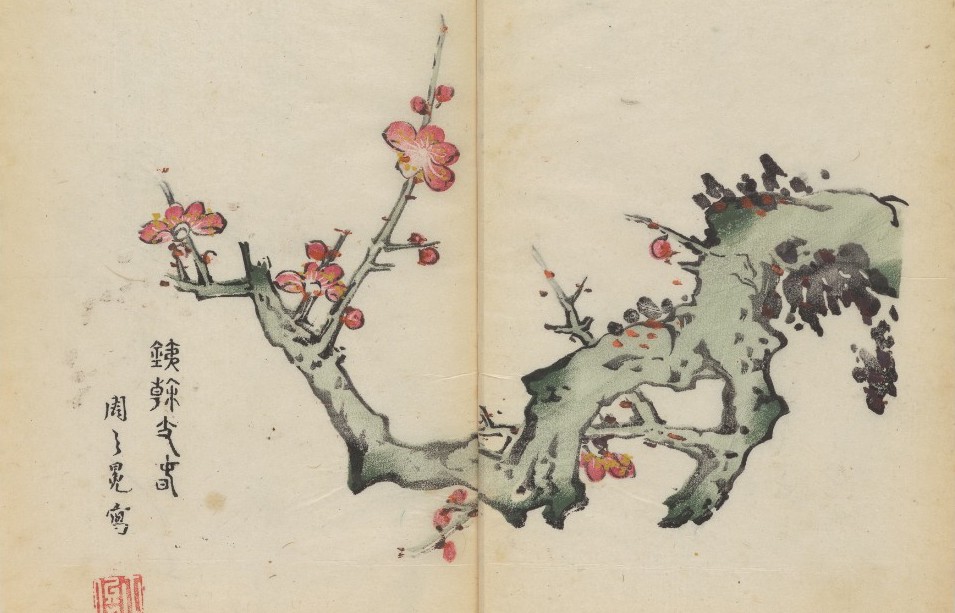

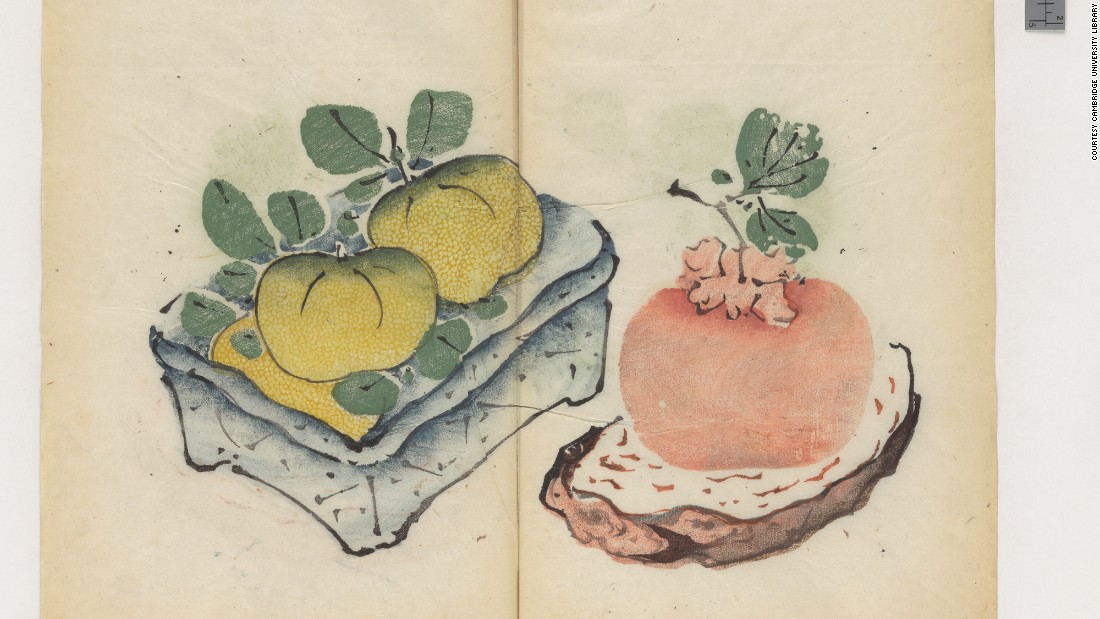

In 1633, a Chinese printer named Hu Zhengyan invented a technique known as douban, a form of polychrome xylography that led to the creation of the world’s oldest multicolor printed book, Shi zhu zhai shu hua pu (Manual of Calligraphy and Painting), containing, perhaps, writes Cambridge University Library, “the most beautiful set of prints ever made.” And now thanks to Cambridge, the manual has been carefully digitized and made available online.

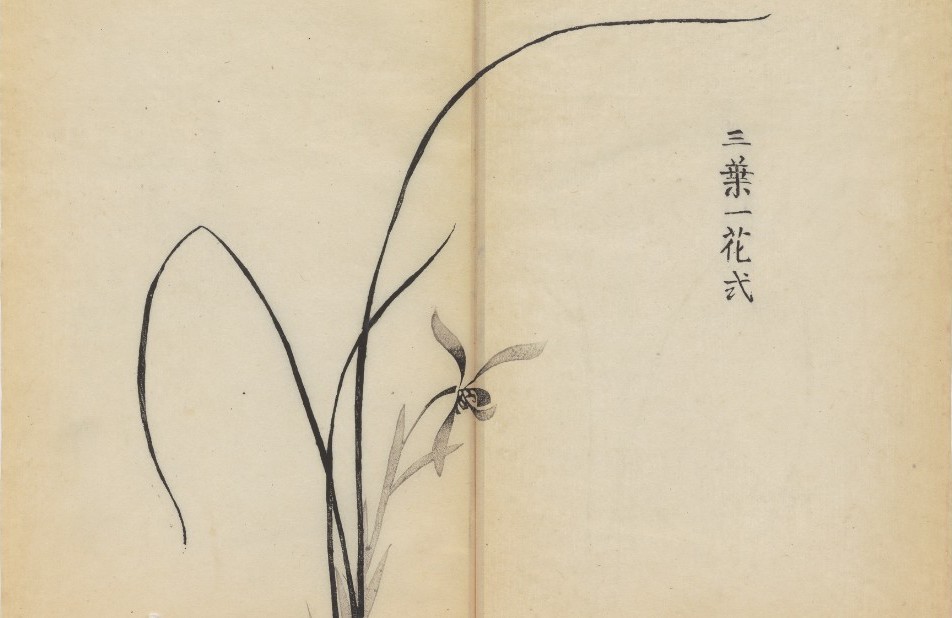

Published by Hu Zhengyan’s Ten Bamboo Studio in Nanjiang, this manual for teachers contains 138 pages of multicolor prints by fifty different artists and calligraphers and 250 pages of accompanying text. “The method” that produced the stunning artifact “involves the use of multiple printing blocks which successively apply different coloured inks to the paper to reproduce the effect of watercolour painting.” Kept untouched in Cambridge’s “most secure vaults,” the book was unsealed for the first time just a couple years ago. “What surprised us,” remarked Charles Aylmer, head of the Library’s Chinese Department, “was the amazing freshness of the images, as if they had never been looked at for over 300 years.”

The 17th century copy is “unique in being complete, in perfect condition and in its original binding.” (Another, incomplete, copy was acquired in 2014 by the Huntington Library in San Marino, CA.) The book contains many “detailed instructions on brush techniques,” writes CNN, “but its phenomenal beauty has meant from the outset that it has held a greater position” than other such manuals. Like another gorgeous multicolor painting textbook, the Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden, made in 1679, this text had a significant impact on the arts in both China and Japan, “where it inspired a whole new branch of printing.”

Considered “one of the most historically and artistically important illustrated books of 17th century Chinese woodblock art,” notes Liesl Bradner at the L.A. Times, Hu Zhengyan’s text reflects a time when literacy levels were rising. Along with them came “increasing consumer demand for the printed word and images, which ushered in a golden era of Chinese pictorial painting.” You can page through digital scans of the entire book, from cover to cover, at the University of Cambridge’s Digital Library. Note: There are 388 pages in total. Click on the arrows at the top of this page to move through the text.

via MetaFilter

Related Content:

Download 2,500 Beautiful Woodblock Prints and Drawings by Japanese Masters (1600–1915)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply