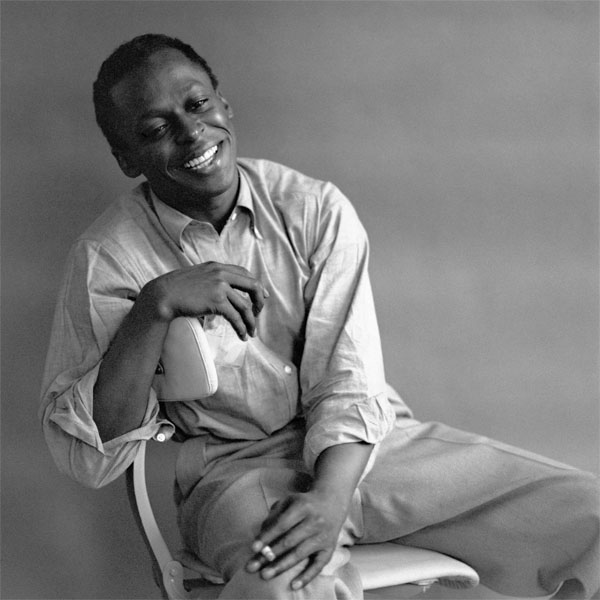

Creative Commons photo by Tom Palumbo

The wandering bards of old disappeared when the printing press came to town. So too have the great bandleaders largely vanished in the age of the super producer and jet-setting DJ. But for a time in the jazz and rock worlds, Olympian figures like Frank Zappa and Miles Davis played several important roles: finding and mentoring the best musicians; mastering old forms and making them new again; serving as curators, arbiters, and contrarians… issuing loud pronouncements on anything and everything as unsparing cultural critics.

Do we need tongues as sharp as Zappa and Davis’s in contemporary pop culture? Maybe, maybe not. They didn’t seem to enjoy much of anything they weren’t directly involved in creating. But man, was it fun to watch them dispense with the niceties and speak their brutal truths. We’ve heard from Zappa on everything from his loathing of the Velvet Underground to the fascism of the PMRC to the morbidity of the entire music industry. Davis’ observations were equally cutting. “His fascinating autobiography,” writes Kirk Hamilton at Kotaku, “is loaded with shit-talking, dismissals, and general acerbic jerkiness. It is fantastic.”

But you needn’t pick up Miles’ book to get an earful of his acid-tongued judgments. We need only revisit the series of “blindfold tests” he did for Downbeat magazine in the fifties and sixties. These experiments had famous musicians listen to new music, “try to pick out who is playing,” then offer their off-the-cuff takes. Davis’ first session, in 1955, began charitably enough, though not without some sweeping criticisms. He dismissed all of the soloists on Clifford Brown’s “Falling in Love with Love,” for example, except for a Swedish pianist whose name escaped him. But he gave the record four stars all the same. “The arrangement was pretty good.”

In 1958, Davis sat for his second blindfold test, with mixed results. He nearly obliterated Tiny Grimes and Coleman Hawkins’ “A Smooth One,” giving it “half a star just because… Hawkins is on it.” But in an effusive moment, he gushes over John Lewis’ “Waremeland (Dear Old Stockholm)” with a ten star rating. “All the stars are for John,” he says. By 1964, little evidence of that rare enthusiasm remained in the third blindfold test. Davis was at that moment, writes Richard Brody, “torn apart.” In a particularly irritable state of mind he “flung insults at Eric Dolphy,” Sonny Rollins, Cecil Taylor, and a few more greats. His commentary “perfectly captures his general distaste,” writes Hamilton, “for, well, everything.”

Of Dolphy’s “Miss Ann” (above), he says, “nobody else could sound that bad!” Of the Jazz Crusaders’ “All Blues”: “What’s that supposed to be? That ain’t nothin’.” Of Duke Ellington, Max Roach and Charles Mingus’ “Caravan”: “What am I supposed to say to that? That’s ridiculous. You see the way they can fuck up music?” Like another infamous trash-talker who currently dominates every conversation with his unbelievable egomania, Davis tosses out the condescending adjective “sad” at every opportunity. Clark Terry’s “Cielito Lindo” is a “sad record.” Dolphy is “a sad motherfucker.” Cecil Taylor’s “Lena” is “some sad shit, man.”

It’s not all bad. Miles loves Stan Getz and Joao Gilberto’s “Desafinando,” giving the record five stars and its two star players the highest of praise. Four years later, his typical mood had not improved. In 1968, Davis sat for his last blindfold test. He tore into Ornette Coleman, mistaking him for Archie Shepp on “Funeral.” Of Freddie Hubbard’s “On the Que-Tee,” he says, “I wouldn’t even put that shit on a record.” Sun Ra’s “Brainville” gets a serious slam: “They must be joking—the Florida A&M band sounds better than that. They should record them, rather than this shit.” It ain’t all pure cattiness. Davis tends to like music that stays out of his musical lane, like The Electric Flag’s “Over Lovin’ You,”—a “nice record,” he says. “It’s a pleasure to get a record like that.” Likewise, the prologue from the Fifth Dimension’s Magic Garden gets a thumbs up.

When Downbeat’s Leonard Feather visited the irascible trumpet player in his hotel room for the last test, the critic “seemed shocked to find records by the Byrds, James Brown, Dionne Warwick, Aretha Franklin, Tony Bennett, and the Fifth Dimension scattered around his room,” notes Davis biographer John Szwed. “Miles seemed to have lost all interest in what was then considered jazz.” No doubt about it, no musician then or now would want to be on the receiving end of his critical barbs. Perhaps the only jazz player he never put down was the “young savant drummer” Tony Williams. Otherwise, “at some point or another,” writes Hamilton, “Davis lays low just about every other luminary in the history of jazz.” But behind the vitriol lay true genius. No one was as competitive—or as demanding of himself as he was of others—as Miles Davis.

Related Content:

Miles Davis Opens for Neil Young and “That Sorry-Ass Cat” Steve Miller at The Fillmore East (1970)

Frank Zappa Explains the Decline of the Music Business (1987)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Yes, the Blindfold Tests are great in general, though they were very frustrating before the internet, because I pretty much never happened to have the recordings they were discussing. I was using Downbeat as a guide to help me navigate into jazz from my rock and roll youth, so I didn’t have much of a collection when I was reading it. Now that you can Google up the recordings and listen along, these Blindfold Tests that they did (and presumably still do) for many decades are a very interesting form of jazz criticism; they could be very harsh sometimes, and they were impressive–I aspired to be able to hear music as well as these people could…playing like them was not even a dream.

As for Miles’s autobiography, yeah, it’s an entertaining monstrosity of a thing, but I think it’s not so great when people get too familiar with the man before they know the music. In a lot of cases, not just Miles.

How on earth does the author compare Miles with Zappa. One is arguably the best musician of the 20th century and the other is a circus curiosity.

That’s exactly what came across my mind as I read that passage! I actually couldn’t believe that he mentioned Zappa in the same breath of Miles and before Miles!! I was insulted to say the least! And anyone that knows anything about music would’ve been just as insulted. Hell, Zappa himself would be appalled that he was mentioned in the same breath of Miles Davis!!’

I also have to totally agree with Miles on the cut by Eric Dolphy. It’s the worst I’ve ever heard him!! I have never heard Dolphy play that way. Now if you want to hear some good Dolphy listen to “Green Dolphin Street”! That’s Eric Dolphy at his best.