What we euphemistically refer to as the “Opening of Japan” catalyzed a period of seismic upheaval for the proud formerly closed country. Between the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1853 and the Meiji restoration in 1868, Japanese society changed rapidly due to the sudden forced influx of foreign capital and influence, much of it destructive. “Unemployment rose,” writes historian John W. Dower, “Domestic prices soared sky high…. Much of Japan was wracked by famine in the mid 1860s…. As if all this were not curse enough, the foreigners also brought cholera with them.” They also brought photography, and both Western and Japanese photographers documented not only the country’s profound transformation, but also its traditional dress and culture.

Closed for 200 years, Japan became a source of endless fascination for Westerners as artifacts made their way across the sea. Among them was “an extensive photographic documentation of Japan,” notes the New York Public Library, and “of interaction between the Japanese and foreigners” (Commodore Perry’s expedition to Tokyo Bay included a daguerreotype photographer.)

“In the broadest sense, photography entered Asia from Europe and America as part of the process of colonialism, but soon took root in those regions with local photographers.”

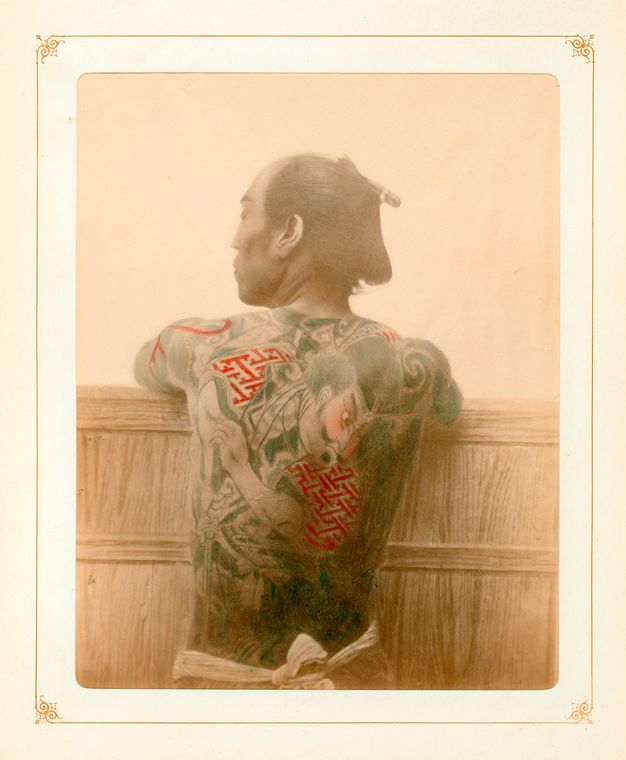

The colorized images you see here come from the NYPL’s large collection of late 19th century Japanese photography, taken by photographers like the Italian-British Felice Beato and his Japanese student Kimbei, who “assisted Beato in the hand-coloring of photographs until 1863,” then “set up his own large and flourishing studio in Yokohama in 1881.” The archive provides “a rich resource for the understanding of the political, social, economic, and artistic history of Asia from the 1870s to the early 20th century.” These images date from between 1890 and 1909, by which time much of Japan had already been extensively westernized in dress, architecture, and style of government.

To many Japanese, the old ways, sustained through a couple hundred years of isolation, must have seemed in danger of slipping away. To many Westerners, however, the encounter with Japan offered a kind of cultural renewal. As the Metropolitan Museum of Art points out, “a tidal wave of foreign imports” from Asia, including “woodcut prints by masters of the ukiyo‑e school… transformed Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art.” European collectors, traders, and artists discovered a mania for all things Japanese, even as some of its cultural forms threatened to disappear. Enter the NYPL’s digital collection, Photographs of Japan, here.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

I’m interested in the culture and dress of the 10th century pictures and text would be appreciated.

I realise things didn’t change much in that time so later evidence would help me form a picture of ancient Japan.