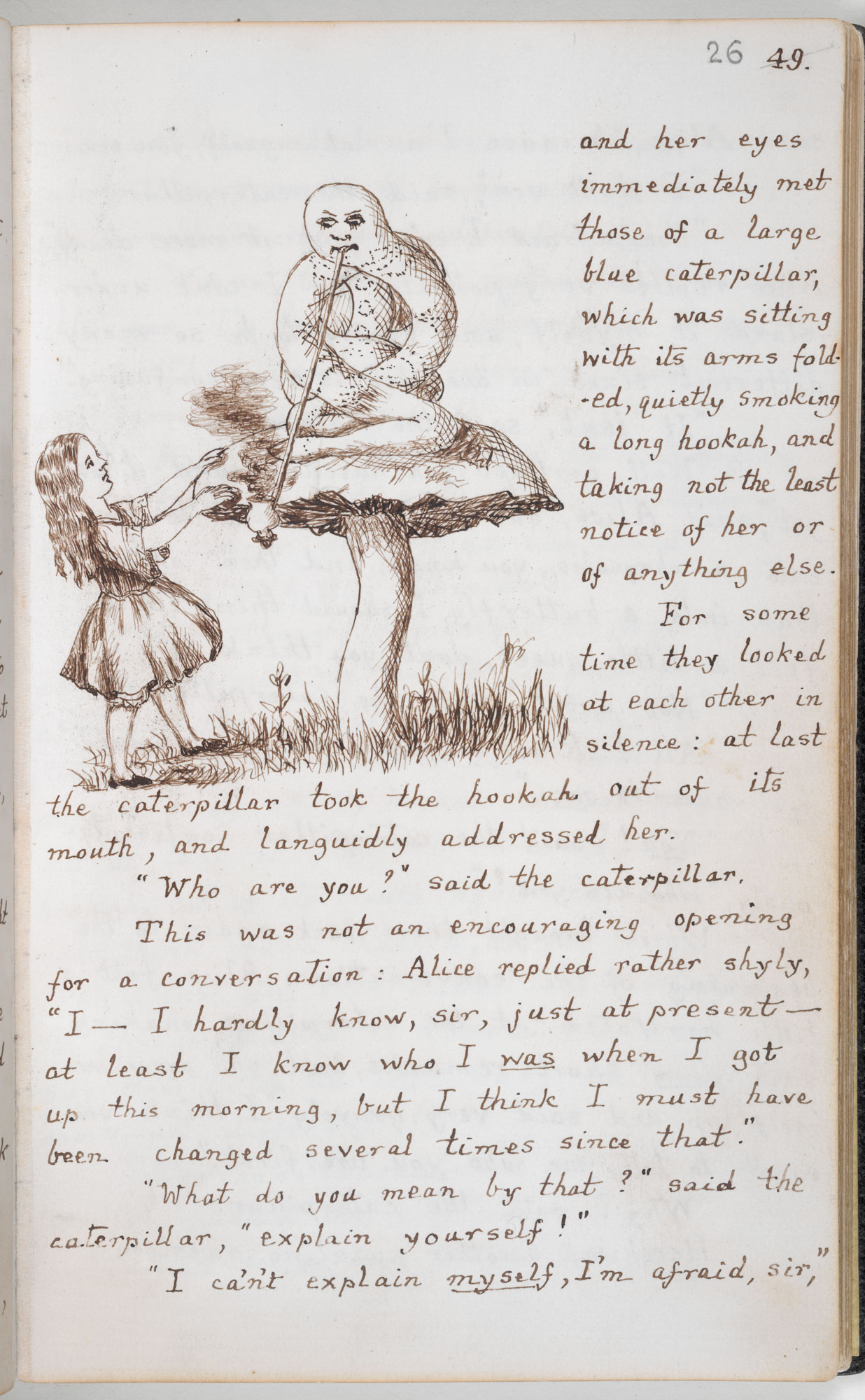

Almost exactly 155 years ago, Lewis Carroll told three young sisters a story. He’d come up with it to enliven a long boat trip up the River Thames, and one of the children aboard, a certain Alice Liddell, enjoyed it so much that she insisted that Carroll commit it to paper. Thus, so the legend has it, was Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland born, although Lewis Carroll, then best known as Oxford mathematics tutor Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, hadn’t taken up his famous pen name yet, and when he did write down Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, it took its first form as Alice’s Adventures Under Ground. You can read that handwritten manuscript, complete with illustrations, at the British Library.

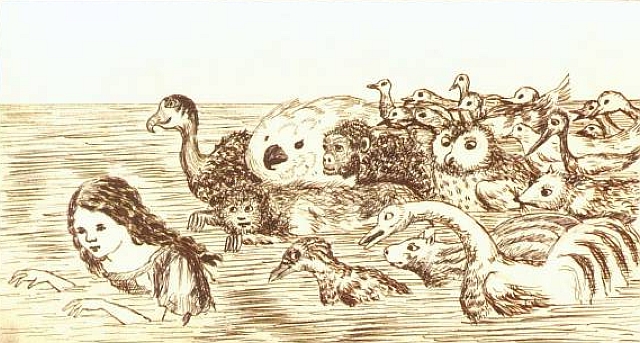

Carroll presented the fictional Alice’s namesake with the manuscript, according to the British Library, as an early Christmas present in 1864. When his friends encouraged him to publish it, he performed a few revisions, “removing some of the family references included for the amusement of the Liddell children,” adding a couple of chapters (the beloved Cheshire Cat and the Mad Hatter’s tea party being among their new material), and enlisting John Tenniel, a Punch magazine cartoonist known for his illustrations of Aesop’s Fables, to create professional art to accompany it. The result, retitled Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, came out in 1865 and has never gone out of print.

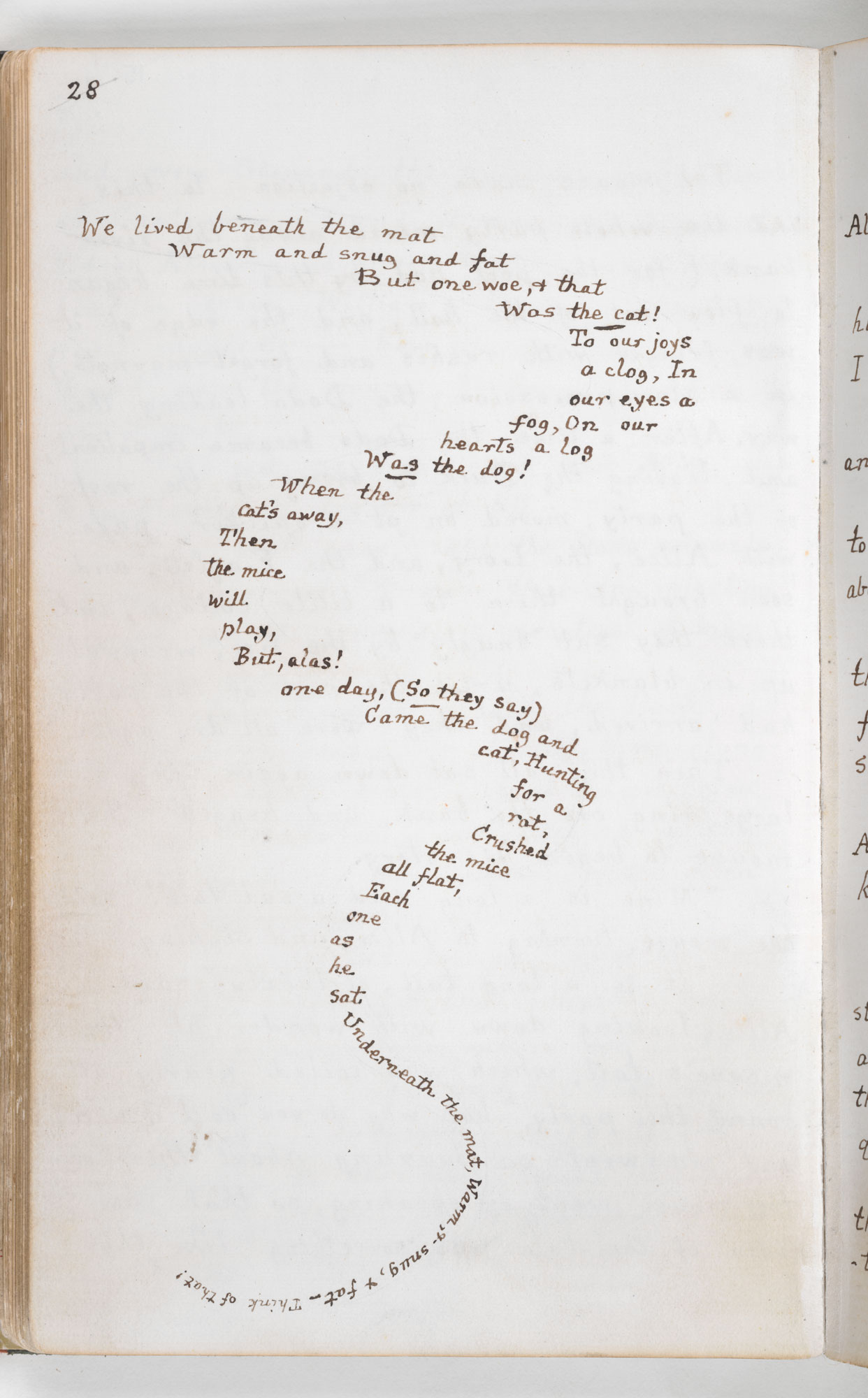

Though Tenniel’s vivid renderings of Alice and the eccentric characters she encounters have remained definitive, plenty of other artists, including Salvador Dalí and Ralph Steadman, have attempted the surely almost irresistible challenge of illustrating Carroll’s highly imaginative story. But today, says Skidmore College professor Catherine J. Golden at The Victorian Web, “critics have reevaluated Carroll’s caricature-style illustration. Carroll expertly intertwines his handwritten text with his pictures to advance the growth motif. His conception of the mouse’s ‘tale’ shaped like an actual mouse’s ‘tail’ is an excellent example of emblematic verse.”

Tenniel, Golden argues, “essentially refashioned with realism and improved upon many of Carroll’s sketchy or anatomically incorrect illustrations, adding domestic interiors and landscapes that appealed to middle-class consumers of the 1860s.” Even “late twentieth-century graphic novel adaptations of Alice in Wonderland recall many of Carroll’s inventive designs as well as those of Tenniel,” which gives Carroll’s original manuscript more claim to having provided the visual basis, not just the textual one, for the following century and a half of sequels official and unofficial, as well as adaptations, reenvisionings, and reimaginings of this “Christmas gift to a dear child in memory of a summer day.”

You can view Carroll’s original manuscript, complete with illustrations, here.

Related Content:

Lewis Carroll’s Photographs of Alice Liddell, the Inspiration for Alice in Wonderland

Photo of the Real Alice in Wonderland Circa 1862

The First Film Adaptation of Alice in Wonderland (1903)

Lewis Carroll’s Classic Story, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Told in Sand Animation

When Aldous Huxley Wrote a Script for Disney’s Alice in Wonderland

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Glad to be quoted in your enjoyable piece! Those interested in learning more about Carroll’s handwritten manuscript as well as Tenniel’s refashionings and late twentieth-century graphic novel adaptions of Alice might enjoy my recent book, Serials to Graphic Novels: The Evolution of the Victorian Illustrated Book. Here is a discount coupon good through July.

Serials to Graphic Novels: The Evolution of the Victorian Illustrated Book

CATHERINE J. GOLDEN

“A valuable and comprehensive survey of an enormous subject. Extremely well-written and a signifcant addition to scholarship.”—Paul Goldman, co-editor of Reading Victorian Illustration, 1855–1875: Spoils of the Lumber Room

“A capacious and synthetic work that draws on a wide variety of scholarship, a very impressive command of the history of book illustration, a huge array of visual and verbal texts, and (most important) a commitment to the genre as a genre in the history of literary and artistic form.”

—Peter Betjemann, author of Talking Shop: The Language of Craft in an Age of Consumption

The Victorian illustrated book came into being, flourished, and evolved during the long nineteenth century. While existing scholarship on Victorian illustrators largely centers on the realist artists of the “Sixties,” this volume examines the entire lifetime of the Victorian illustrated book. Catherine Golden o ers a new framework for viewing the arc of this vibrant genre, arguing that it arose from and continually built on the creative vision of the caricature-style illustrators of the 1830s. She surveys the uidity of illustration styles across serial installments, British and American periodicals, adult and children’s literature, and–more recently–graphic novels. Serials to Graphic Novels examines widely recognized illustrated texts, such as The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, Alice in Wonderland, Peter Rabbit, and

Trilby. Golden explores factors that contributed to the early popularity of the

illustrated book—the growth of commodity culture, a rise in literacy, new

printing technologies—and that ultimately created a mass market for illustrated ction.

Golden identifes present-day visual adaptations of the works of Austen, Dickens, and Trollope as well as original Neo-Victorian graphic novels like The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and Victorian-themed novels like Batman: Noël as the heirs to the Victorian illustrated book. With these adaptations and additions, the Victorian canon has been refashioned and repurposed visually for new generations of readers.

CATHERINE J. GOLDEN, professor of English and the Tisch Chair in Arts and Letters at Skidmore College, is author of numerous books, including Posting It: The Victorian Revolution in Letter Writing.

Special discount of $40 is available through July 31, 2017

TO ORDER:

CALL 800–226-3822 and have VISA, MasterCard,

American Express, or Discover number handy. MAIL completed order form with check payable

to University Press of Florida to: University Press of Florida

15 NW 15th Street Gainesville, FL 32603–1933

ONLINE at http://www.upf.com

Enter discount code AU717 at checkout

*Postage and handling fee:

USA: $6.00 for the first book, $1.00 for each additional book.

Int’l: $15.00 for the first book, $10.00 for each additional book.

UNIVERSITY PRESS OF FLORIDA 800.226.3822 · http://WWW.UPF.COM

Discount Code: AU717