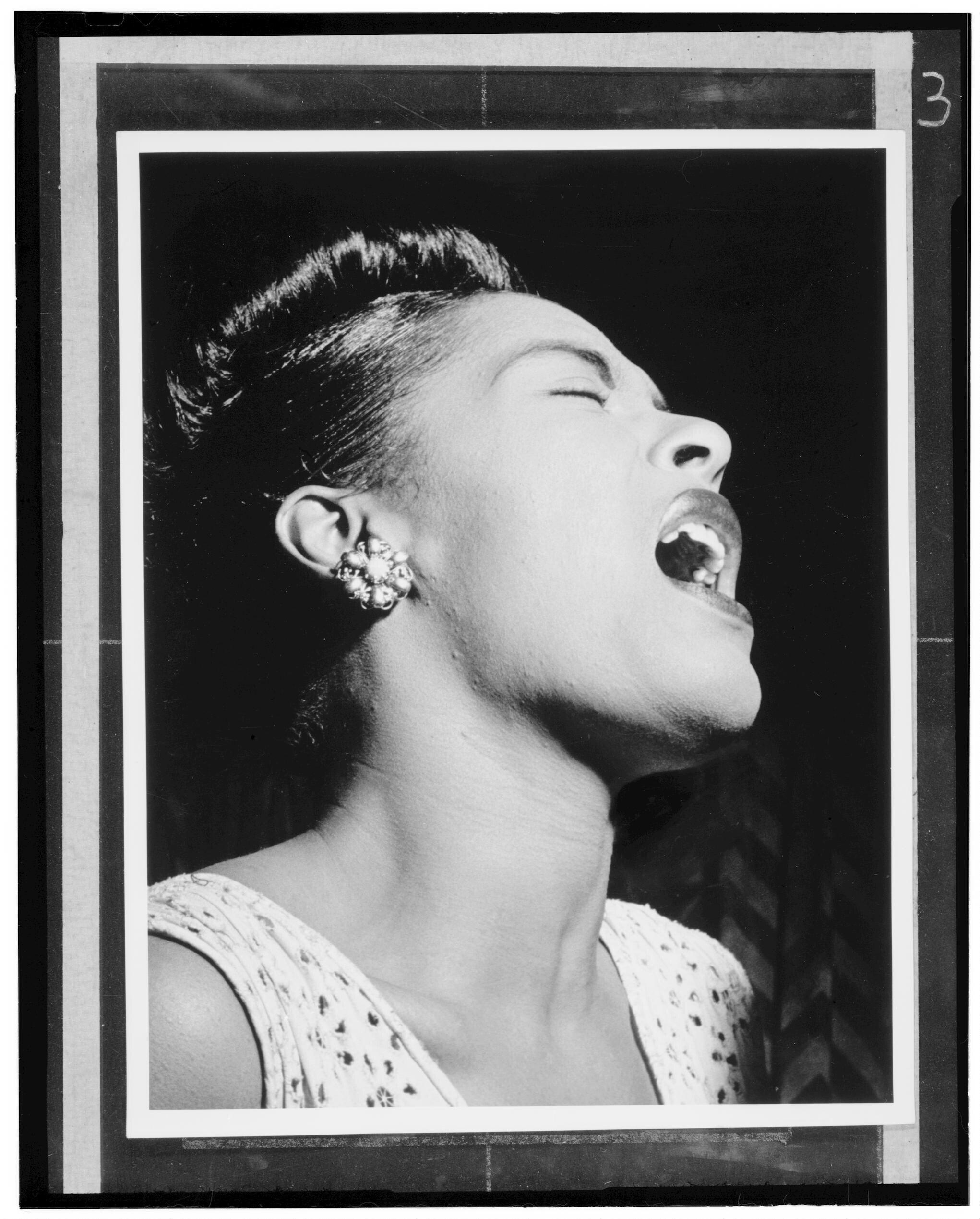

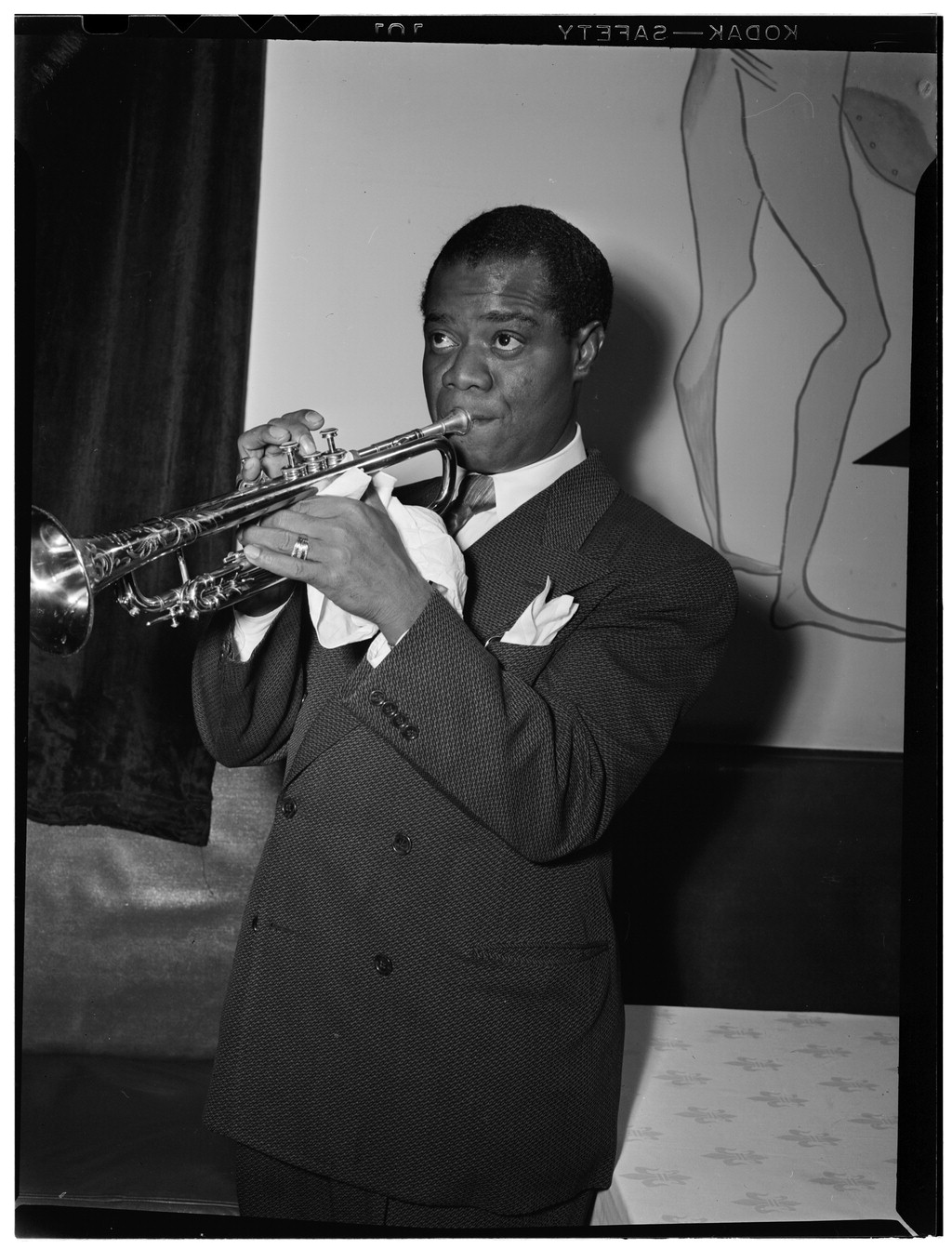

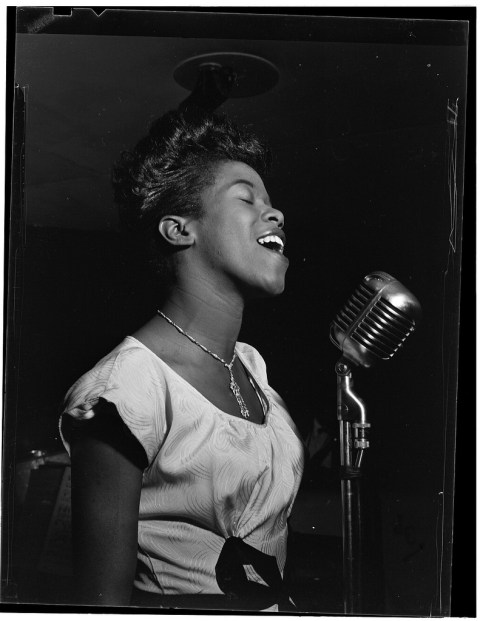

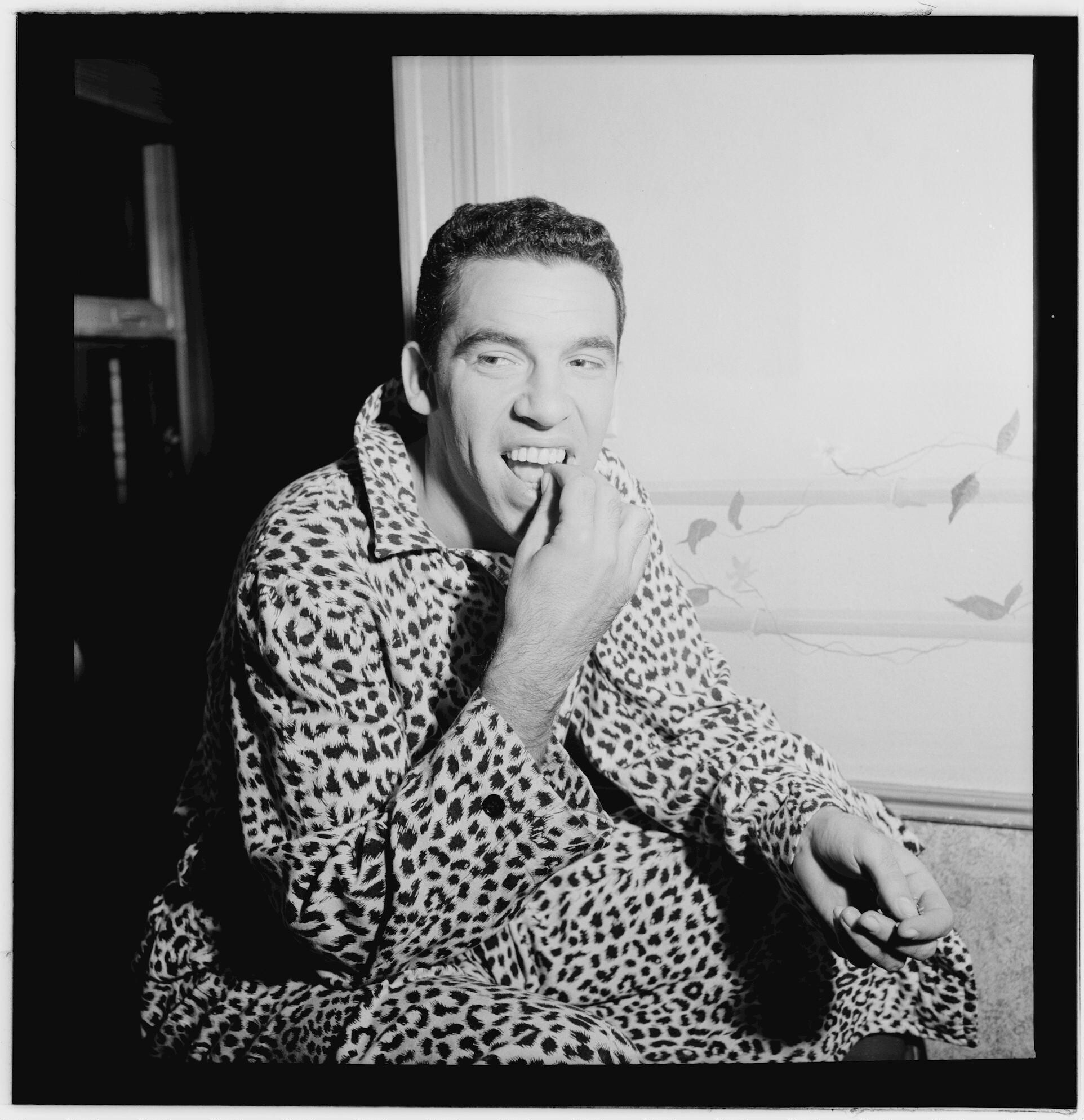

If you’ve seen the most famous photographs of Billie Holiday, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Frank Sinatra, Django Reinhardt, or nearly any other jazz legend from the mid-20th century, you’ve seen the work of William P. Gottlieb. His photos have graced many a classic album cover, magazine spread, and poster. “Between 1938 and 1948,” writes Maria Popova, Gottlieb “documented the jazz scene in New York City and Washington, D.C., and created what eventually became some of history’s most iconic portraits of jazz greats.” He initially did so as a self-taught amateur, a jazz columnist whose photography was “an afterthought,” notes Gottlieb’s 2006 Washington Post obituary,” mere visual accompaniment to his regular work.”

As Gottlieb once told The New York Times, “I got into photography because The Post was stingy and wouldn’t pay photographers to cover my 11 o’clock concerts.” But he developed an undeniably keen eye for performance.

As Gottlieb once told The New York Times, “I got into photography because The Post was stingy and wouldn’t pay photographers to cover my 11 o’clock concerts.” But he developed an undeniably keen eye for performance.

What’s more, his work is deeply informed by affection and empathy. Gottlieb was an artist who had warm relationships with his subjects. He took the photo at the top, perhaps the most famous image of Billie Holiday, in 1947, when the singer “was at her peak,” he wrote, “musically and physically”—two years clean and sober after her time in a federal prison.

“Regrettably,” he writes, “Billie regressed.” Gottlieb tells the heartbreaking story of the last time he went to see her. The “audience waited… and waited.” The photographer, “playing a hunch,” went backstage to find her “pretty much ‘out of it.’”

I helped her finish dressing, then led her to the microphone. She looked horrible. She sounded worse. I replaced my notebook in my pocket, put a lens cap on my camera, and walked away, choosing to remember this remarkable woman as she once was.

Most of Gottlieb’s stories are not nearly so tragic. Take his last run-in with Louis Armstrong, at their dentist office’s waiting room. “After small talk,” he wrote, “Satchmo looked me over, deciding I, too, had been gaining weight. He reached into his jacket pocket, pulled out a printed diet (that he kept for friends-in-need), and handed me a copy. ‘Pops,’ he said, ‘try this.’ I quickly noted that it featured Pluto Water [a laxative]. But I thanked him, anyway.”

Gottlieb retired from photography and jazz writing in the fifties and made a career as a children’s book author and educational film producer. In 1979, he published 219 of his best photographs in a book called The Golden Age of Jazz, and in 2010, much of Gottlieb’s work entered the public domain, according to The Library of Congress (LOC). You can see hundreds of his photographs—famous images like those of Sarah Vaughan, further up, Thelonious Monk, above, Buddy Rich, below, and so many more—at the Library of Congress’s online William P. Gottlieb Collection. The LOC describes the collection thus:

The online collection provides access to digital images of all sixteen hundred negatives and transparencies, approximately one hundred annotated contact prints, and over two hundred selected photographic prints that show Gottlieb’s cropping, burning, and dodging preferences. One can follow the artist’s work process by examining first a raw negative, then an annotated contact print, and finally a finished, published product. The Web site also includes digital images of Down Beat magazine articles in which Gottlieb’s photographs were first published. Other special features of the online presentation are audio clips of Gottlieb discussing specific photographs, articles about the collection from Civilization magazine and the Library of Congress Information Bulletin, an essay describing Gottlieb’s life and work, and a “Gottlieb on Assignment” section that showcases Down Beat articles about Thelonious Monk, Dardanelle, Willie “the Lion” Smith, and Buddy Rich.

You can also download high resolution versions of nearly every image in the archive. (To purchase prints, see Gottlieb’s online gallery, Jazz Photos.) There may be no better way, short of actually being there and meeting the stars, to witness the golden age of jazz than through the eyes and ears of such a sympathetic observer as William P. Gottlieb. Enter the collection here.

Related Content:

Hear 2,000 Recordings of the Most Essential Jazz Songs: A Huge Playlist for Your Jazz Education

Stanley Kubrick’s Jazz Photography and The Film He Almost Made About Jazz Under Nazi Rule

How “America’s First Drug Czar” Waged War Against Billie Holiday and Other Jazz Legends

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply