You’d be forgiven for assuming that the Bauhaus, the modern art and design movement that emerged from the eponymous German art school in the 1920s and 30s, didn’t involve many women. Perhaps the famous near-industrial austerity of its aesthetic, especially at large scales, has stereotypical associations with maleness, but also, Bauhaus’ most oft-referenced leading lights — Paul Klee, Walter Gropius, Wassily Kandinsky, László Moholy-Nagy, Oskar Schlemmer — all happened to be men. But if we seek out the women of the Bauhaus, what can we learn?

“When it opened, the Bauhaus school declared itself progressive and modern and advocated equality for the sexes, which was rare at the time,” says Evelyn Adams in her short video on the Women of the Bauhaus above. “Value was placed on skill rather than gender. Classes weren’t segregated, and women were free to select whichever subjects they wanted.”

This had an understandable appeal, and in the school’s first year more women applied than men. But alas, “in reality, despite having radical aspirations, the men in charge of the school represented the societal attitudes of the time. If everyone was welcomed as equals, then why did none of the women reach the same level of recognition as Paul Klee or Wassily Kandinsky?”

The story of Gertrud Arndt, one of whose self-portraits appears above and one of whose textiles appears below that, sheds some light on the answer. “She must have felt so optimistic,” writes the New York Times’ Alice Rawsthorn, when she arrived at the Bauhaus school of art and design in 1923 as “a gifted, spirited 20-year-old who had won a scholarship to pay for her studies. Having spent several years working as an apprentice to a firm of architects, she had set her heart on studying architecture.” But because of a “long-running battle between its founding director, the architect Walter Gropius, and one of its most charismatic teachers, Johannes Itten, who wanted to use the school as a vehicle for his quasi-spiritual approach to art and design,” the Bauhaus’ house, as it were, had fallen out of order.

Alas, “Arndt was told that there was no architecture course for her to join and was dispatched to the weaving workshop.” In recent years, the Bauhaus Archive in Berlin has put on shows to honor female Bauhausers like Ardnt, textile designer Benita Koch-Otte, and theater designer, illustrator, and color theorist Lou Scheper-Berkenkamp. “The situation improved after Gropius succeeded in ousting Itten in 1923,” writes Rawsthorn, hiring Moholy-Nagy in Itten’s place. “Having ensured that female students were given greater freedom, Moholy encouraged one of them, Marianne Brandt, to join the metal workshop. She was to become one of Germany’s foremost industrial designers during the 1930s,” and her 1924 tea infuser and strainer appears just above.

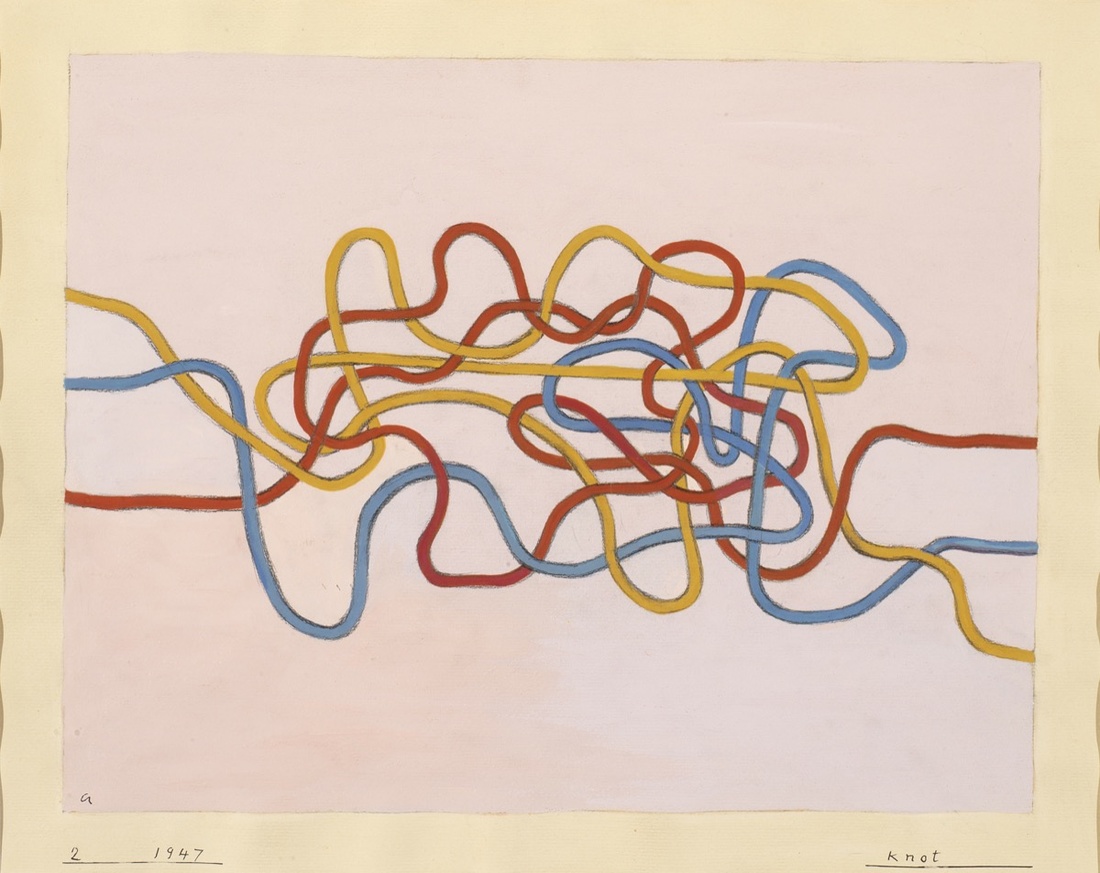

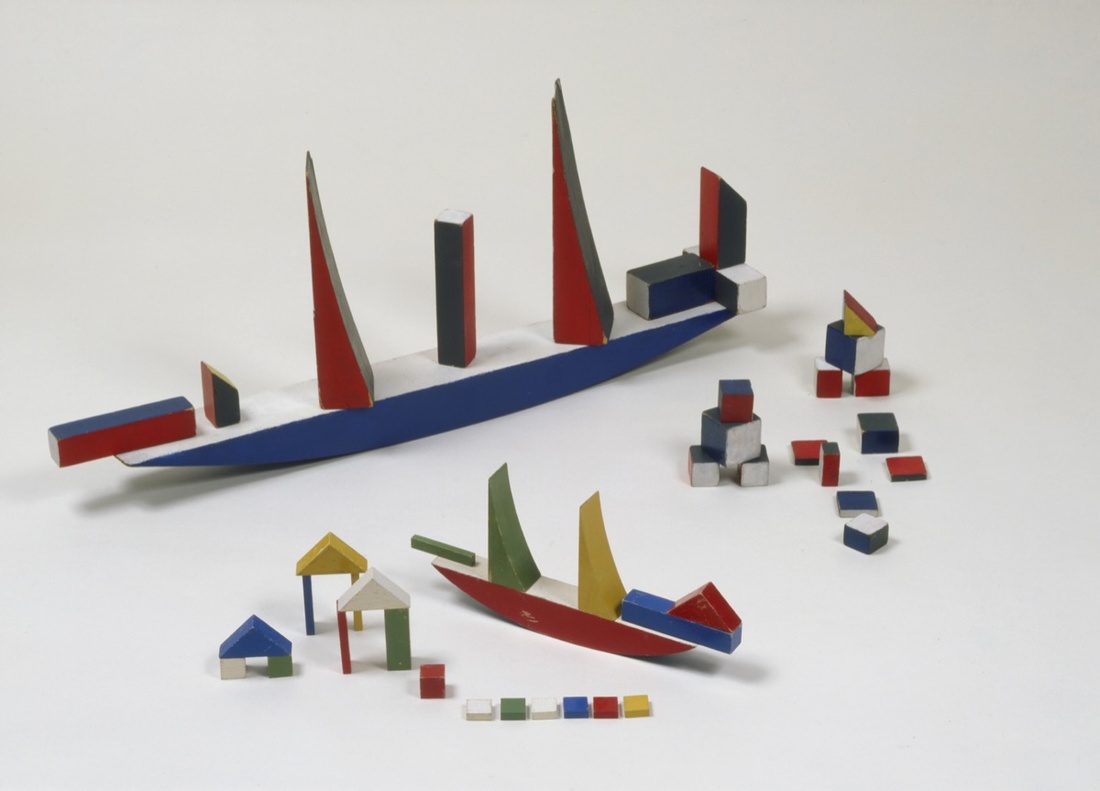

Artsy’s Alexxa Gotthardt has the stories of more women of the Bauhaus, including Anni Albers, whose 1947 Knot 2 appears just above. Her other work includes “a cotton and cellophane curtain that simultaneously absorbed sound and reflected light” and tapestries that “would go on to have a considerable impact on the development of geometric abstraction in the visual arts.” Alma Siedhoff-Buscher, writes Gotthardt, dared “to switch from the weaving workshop to the male-dominated wood-sculpture department,” where she invented a “small ship-building game,” pictured below and still in production today, that “manifested Bauhaus’s central tenets: its 22 blocks, forged in primary colors, could be constructed into the shape of a boat, but could also be rearranged to allow for creative experimentation.”

Bauhaus art and design took criticism in its heyday, as it still takes criticism now, for a certain coldness and sterility — or at least the work of the men of the Bauhaus does. But the more we discover about the lesser-known women of the Bauhaus, the more we see how they managed to bring no small degree of humanity to its artistic fruits, even to those of its most rigorous branches. “There is no difference between the beautiful sex and the strong sex,” Gropius once insisted in a somewhat self-defeating pronouncement, but the differences between the male and female Bauhausers — in their personalities as well as in their work — make the movement look all the richer in retrospect.

Related Content:

32,000+ Bauhaus Art Objects Made Available Online by Harvard Museum Website

Bauhaus, Modernism & Other Design Movements Explained by New Animated Video Series

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Let’s identify one of my favorite photos, the geometric planets costumes from Oscar Schlemmer’s Das Triadische Ballett 1922 by Bauhaus Theater, which toured Europe in the 1930s. The clumsy costumes intentionally limited movement.

Marguerite Wildenhain and the Bauhaus: An Eyewitness Anthology. Dean and Geraldine Schwarz.