No one sings as purely as those who inhabit the deepest hell—what we take to be the song of angels is their song.

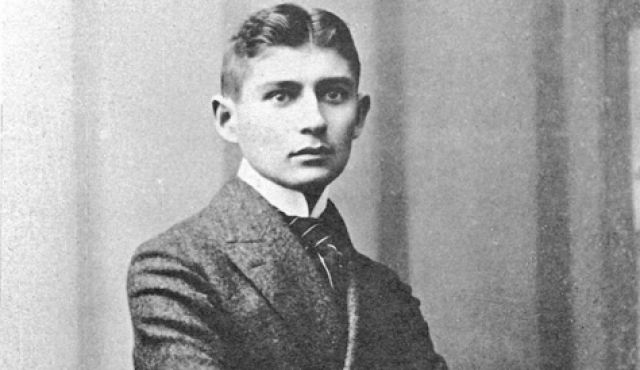

Poor Kafka, born too early to blame his writer’s block on 21st-century digital excuses: social media addiction, cell phone addiction, streaming video…

Would The Metamorphosis have turned out differently had its author had access to a machine that would have allowed him to self-publish, communicate facelessly, and dispense entirely with typists, pens and paper?

Had Kafka had his way, his friend and fellow writer, Max Brod, would have carried out instructions to burn his unpublished work—including letters and journal entries—upon his death.

Instead Brod published them.

How horrified would their author be to read The New Yorker’s opinion that his journals should be regarded as one of his major literary achievements? A Kafka-esque response might be the mildest reaction warranted by the situation:

His life and personality were perfectly suited to the diary form, and in these pages he reveals what he customarily hid from the world.

These once-private pages (available in book format here) reveal a not-unfamiliar writerly tendency to agonize over a perceived lack of output:

JANUARY 20, 1915: The end of writing. When will it take me up again?

JANUARY 29, 1915: Again tried to write, virtually useless.

JANUARY 30, 1915: The old incapacity. Interrupted my writing for barely ten days and already cast out. Once again prodigious efforts stand before me. You have to dive down, as it were, and sink more rapidly than that which sinks in advance of you.

FEBRUARY 7, 1915: Complete standstill. Unending torments.

MARCH 11, 1915: How time flies; another ten days and I have achieved nothing. It doesn’t come off. A page now and then is successful, but I can’t keep it up, the next day I am powerless.

MARCH 13, 1915: Lack of appetite, fear of getting back late in the evening; but above all the thought that I wrote nothing yesterday, that I keep getting farther and farther from it, and am in danger of losing everything I have laboriously achieved these past six months. Provided proof of this by writing one and a half wretched pages of a new story that I have already decided to discard…. Occasionally I feel an unhappiness that almost dismembers me, and at the same time am convinced of its necessity and of the existence of a goal to which one makes one’s way by undergoing every kind of unhappiness.

Psychology Today identifies five possible underlying causes for such inactivity, and tips for surmounting them. It seems likely the fastidious, self-absorbed Kafka would have rejected them on their breezy tone alone, but perhaps other less persnickety individuals will find something of use:

1. You’ve Lost Your Way

If you’re stalled because you lost your way, try the opposite of what you usually do—if you’re a plotter, give your imagination free rein for a day; if you’re a freewriter or a pantser, spend a day creating a list of the next 10 scenes that need to happen. This gives your brain a challenge, and for this reason you can take heart, because your billions of neurons love a challenge and are in search of synapses they can form.

2. Your Passion Has Waned

Remember, your writing brain looks for and responds to patterns, so be careful that you don’t make succumbing to boredom or surrendering projects without a fight into a habit. Do your best to work through the reasons you got stalled and to finish what you started. This will lay down a neuronal pathway that your writing brain will merrily travel along in future work.

3. Your Expectations Are Too High

Instead of setting your sights too high, give yourself permission to write anything, on topic or off topic, meaningful or trite, useful or folly. The point is that by attaching so much importance to the work you’re about to do, you make it harder to get into the flow. Also, if your inner critic sticks her nose in (which often happens), tell her that her role is very important to you (and it is!) and that you will summon her when you have something worthy of her attention.

4. You Are Burned Out

You aren’t blocked; you’re exhausted. Give yourself a few days to really rest. Lie on a sofa and watch movies, take long walks in the hour just before dusk, go out to dinner with friends, or take a mini-vacation somewhere restful. Do so with the intention to give yourself—and your brain—a rest. No thinking about your novel for a week! In fact, no heavy thinking for a week. Lie back, have a margarita, and chill.

5. You’re Too Distracted

Take note that, unless you’re just one of those rare birds who always write no matter what, you will experience times in your life when it’s impossible to keep to a writing schedule. People get sick, people have to take a second job, children need extra attention, parents need extra attention, and so on. If you’re in one of those emergency situations (raising small children counts), by all means, don’t berate yourself. Sometimes it’s simply necessary to put the actual writing on hold. It is good, however, to keep your hands in the water. For instance, in lieu of writing your novel:

Read works similar to what you hope to write.

Read books related to the subject you’re writing about.

Keep a designated journal where you jot down ideas for the book (and other works).

Write small vignettes or sketches related to the book

Whenever you find time to meditate, envision yourself writing the book, bringing it to full completion.

Make writing the book a priority.

Additionally, you may find some merit in enlisting a friend to publish, I mean, burn the above-mentioned journals posthumously. Just don’t write anything you wouldn’t want the public to see.

Read author Susan Reynolds’ complete Psychology Today advice for blocked writers here.

Have a peek at Kafka’s Diaries: 1910–1923 here.

via Austin Kleon

Related Content:

Franz Kafka’s Kafkaesque Love Letters

Franz Kafka: An Animated Introduction to His Literary Genius

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine, currently appearing onstage in New York City in Paul David Young’s Faust 3. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Leave a Reply