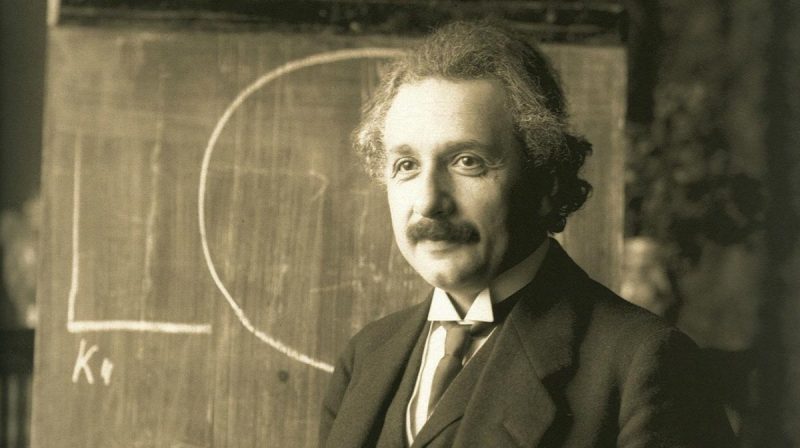

Image by Ferdinand Schmutzer, via Wikimedia Commons

Albert Einstein was a complicated human being, with a wide range of interests. His personality seemed balanced between a certain chilliness when it came to personal matters, and a great deal of warmth and compassion when it came to the wider human family. The physicist struck up friendships with famed American activists Paul Robeson, Marian Anderson, and W.E.B. Du Bois, and he championed the cause of Civil Rights in the U.S. He professed a deep admiration for Gandhi, and praised him several times in letters and speeches. And in 1955, just days before his death, Einstein collaborated with another outspoken public intellectual, Bertrand Russell, on a peace manifesto, which was signed by six other scientists.

Einstein saw a public role for scientists in matters social, political, and even economic. In 1949, he published an article in the Monthly Review titled “Why Socialism?” Anticipating his critics, he begins by asking “is it advisable for one who is not an expert on economic and social issues to express views on the subject of socialism?” To which he replies, “I believe for a number of reasons that it is.”

Einstein goes on, sounding something like a combination of Karl Marx and E.O. Wilson, to elaborate the theoretical basis for socialism as he sees it, first describing what Marx called “primitive accumulation” and what the socialist economist Thorstein Veblen called “’the predatory phase’ of human development.”

…most of the major states of history owed their existence to conquest. The conquering peoples established themselves, legally and economically, as the privileged class of the conquered country. They seized for themselves a monopoly of the land ownership and appointed a priesthood from among their own ranks. The priests, in control of education, made the class division of society into a permanent institution and created a system of values by which the people were thenceforth, to a large extent unconsciously, guided in their social behavior.

The science of economics, as it stands, writes Einstein, still belongs “to that phase.” Such “laws as we can derive” from “the observable economic facts… are not applicable to other phases.” These facts simply describe the predatory state of affairs, and Einstein implies that not even economists have sufficient methods to definitively answer the question “why socialism?”—“economic science in its present state can throw little light on the socialist society of the future.” We should not assume, then, he goes on, “that experts are the only ones who have a right to express themselves on questions affecting the organization of society.” Einstein himself doesn’t pretend to have all the answers. He ends his essay, in fact, with a few questions addressing “some extremely difficult socio-political problems,” of the kind that attend every debate about socialism:

…how is it possible, in view of the far-reaching centralization of political and economic power, to prevent bureaucracy from becoming all-powerful and overweening? How can the rights of the individual be protected and therewith a democratic counterweight to the power of bureaucracy be assured?

Nevertheless, Einstein is “convinced” that the only way to eliminate the “grave evils” of capitalism is “through the establishment of a socialist economy, accompanied by an educational system which would be oriented toward social goals.” For Einstein, the “worst evil” of predatory capitalism is the “crippling of individuals” through an educational system that emphasizes an “exaggerated competitive attitude” and trains students “to worship acquisitive success.” But the problems extend far beyond the individual and into the very nature of the political order.

Private capital tends to become concentrated in few hands… The result of these developments is an oligarchy of private capital the enormous power of which cannot be effectively checked even by a democratically organized political society. This is true since the members of legislative bodies are selected by political parties, largely financed or otherwise influenced by private capitalists who, for all practical purposes, separate the electorate from the legislature. The consequence is that the representatives of the people do not in fact sufficiently protect the interests of the underprivileged sections of the population. Moreover, under existing conditions, private capitalists inevitably control, directly or indirectly, the main sources of information (press, radio, education). It is thus extremely difficult, and indeed in most cases quite impossible, for the individual citizen to come to objective conclusions and to make intelligent use of his political rights.

The political economy Einstein describes is one often lambasted by right libertarians as an impure variety of crony capitalism, one not worthy of the name, but the physicist is skeptical of the claim, writing “there is no such thing as a pure capitalist society.” Private owners always secure their privileges through the manipulation of the political and educational systems and the mass media.

The predatory situation Einstein observes is one of extreme alienation among all classes; “All human beings, whatever their position in society, are suffering from this process of deterioration. Unknowingly prisoners of their own egotism, they feel insecure, lonely, and deprived of the naïve, simple, and unsophisticated enjoyment of life. Man can find meaning in life, short and perilous as it is, only through devoting himself to society.” Einstein believed that devotion should take the form of a socialist economy that promotes both the physical wellbeing and the political rights of everyone. But he did not presume to know exactly what such an economic future would look like, nor how it might come into being. Read his full essay, “Why Socialism?” here.

Related Content:

Albert Einstein Expresses His Admiration for Mahatma Gandhi, in Letter and Audio

Albert Einstein Imposes on His First Wife a Cruel List of Marital Demands

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

beautiful site

This article is not intellectually stimulating in the least. reading the essay itself is a better use of time rather than this watered down version.