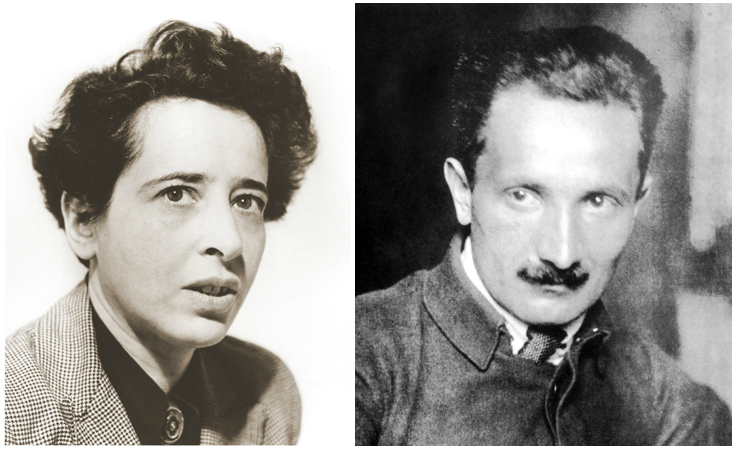

The notorious four-year affair between Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger has occasioned many a bitter academic debate, for reasons with which you may already be familiar. If not, Alan Ryan sums it up succinctly in a 1996 New York Review of Books essay:

She was a Jew who fled Germany in August 1933, a few months after Hitler’s assumption of power. He was elected Rector of the University of Freiburg in the spring of 1933, and in a notorious inaugural address hailed the presence of the brown-shirted storm-troopers in his audience, claimed that Hitler would restore the German people to spiritual health, and ended by giving the familiar stiff-armed Nazi salute to cries of “Sieg Heil.” The thought that these two were ever soulmates is hard to swallow.

Arendt went on to write The Origins of Totalitarianism and Eichmann in Jerusalem, in which she used the phrase “banality of evil” for the Nazi functionary on trial at Nuremberg. Heidegger refused to discuss his collaboration publicly and “remained silent about the extermination of the Jews, about the terrorism of Hitler’s regime.” But as we’ve learned from his recently published journals, the so-called Black Notebooks, he was privately a “convinced Nazi,” as Peter Gordon observes, who “did not awaken from his philosophical-political fantasies. They only grew more extreme.”

But indeed, Arendt and Heidegger were in love, during an affair that began when she was an 18-year-old student and he her married 36-year-old professor. Their letters show an illicit relationship developing from caution to infatuation. Heidegger waxed romantically philosophical:

.…we become what we love and yet remain ourselves. Then we want to thank the beloved, but find nothing that suffices.

We can only thank with our selves. Love transforms gratitude into loyalty to our selves and unconditional faith in the other. That is how love steadily intensifies its innermost secret.

But both of them knew the relationship could not last, and Heidegger suggested that moving on from him would be in her best interest as a young scholar. In 1929, Arendt met and became engaged to a German journalist and classmate in Heidegger’s seminar. She sent her professor a note on her wedding day which begins, “Do not forget me, and do not forget how much and how deeply I know that our love has become the blessing of my life.”

Before his Nazi appointment, Arendt wrote to her former lover and mentor in 1932 or 33 upon hearing rumors “about Heidegger’s sympathy with National Socialism.” (Her letter has been lost.) He replied with a number of excuses for specific acts—such as refusing to supervise Jewish students—and assured her of his feelings, but “nowhere in the letter is there any denial of Nazi sympathies,” writes Adam Kirsch at The New Yorker. The two met after the war in Freiburg, and Heidegger later sent Arendt a passionate, poetic letter in 1950, extolling the “exciting, still almost unspoken understanding” between them, “emerging from an affinity that was created so quickly, that comes from so far away, that has not been shaken by evil and confusion.”

Later, in a 1969 birthday tribute essay “Martin Heidegger at Eighty,” Arendt penned what has generally been taken as an exoneration of Heidegger. In it, she “compared Heidegger to Thales,” writes Gordon, “the ancient philosopher who grew so absorbed in contemplating the heavens that he stumbled into the well at his feet.” The truth is quite a bit more complicated than that, and quite a bit less lofty. But as Maria Popova eloquently writes, their relationship “exposes the complexity and contradiction of which the human spirit is woven, its threads nowhere more ragged than in love.” Read many more excerpts from their letters at Brain Pickings. And find complete letters collected in the volume, Letters: 1925–1975 — Martin Heidegger and Hannah Arendt.

via Brain Pickings

Related Content:

Heidegger’s “Black Notebooks” Suggest He Was a Serious Anti-Semite, Not Just a Naive Nazi

Martin Heidegger Talks Philosophy with a Buddhist Monk on German Television (1963)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

You make a grave factual error, one that reveals you’ve never read the book, here. Eichmann was not on trial at Nuremberg.

Yes. Terrible error. The Eichmann´s trial Took place in Jerusalem.