If you were to ask a random group of reasonably well-educated 21st century people to name the most pressing issues of the 1800s, you would likely find at the top of the list words like “slavery” or “the ‘woman question.’” And indeed, these issues determined much of the course of 19th century history (and the furious and hair-tearingly frustrating politics of today). But if you were to travel back in time to ask a number of 19th century people to name their topmost concerns, you’d likely find that not a few of them would discuss the problem of.… Ghosts.

Along with Abolitionism and Feminism, one of the most significant movements to emerge from the Victorian era was Spiritualism, and it was a serious business, in both an idiomatic and economic sense. Psychics and mediums preyed on credulous and grief-stricken people hoping to reconnect with lost loved ones. Hoaxes abounded, skeptics and true believers formed societies and published literature. You might say that for Victorians, “Spirits” had all the cultural power that UFOs had for post-war Americans. So influential was Spiritualism that it inspired many of the leading intellectuals in England to found an exclusive club devoted to pursuing the paranormal.

The membership of “The Ghost Club,” as it was called, included since its official founding in 1862 such luminaries as Charles Dickens (an original member), W.B. Yeats, Arthur Conan Doyle, and a fair number of prominent writers and academics, clerics, politicians, and scientists. “This was not a club for your average schlub,” writes author Julia Tibbott, given its “origins on the hallowed grounds at Cambridge” with informal conversations in the 1850s. With its intellectual bent, it was also not an organization prone to blind faith, but functioned at times like a genteel type of Mythbusters. “The members of the club would not only talk about the paranormal,” explains Kelly McClure at the Destination America blog, but they would

…use their combined book smarts to attempt to prove or de-bunk claims of the otherworldly. One of the first investigations they conducted was to determine if The Davenport brothers could really contact the dead using something they called a “spirit cabinet.” In the end it was concluded that, no, they could not.

The question of spirits in the 19th century was treated as both a metaphysical and a scientific one, and was pursued with vigor next to all kinds of other logical methods and pieties. “Zealous defenders of the traditional Christian doctrine like Thomas Carlyle or John Ruskin,” explains Dickens scholar Soumya Chakrabarty, “argued in favour of the supremacy of spiritual vision,” and thus the possible validity of ghost sightings. Sir Walter Scott “saw ghost sightings as optical illusions,” and Scottish physician John Ferriar—who wrote an early treatise on the subject—“saw ghosts simply as vivid visual memories that keep coming back.”

Of course many people disapproved of such investigations, considering them heretical to religious, philosophical, or scientific doctrines. Therefore, the Ghost Club “kept scant records of their meetings, so members were able to speak freely about their beliefs without fear of ridicule—sort of a ‘Spiritualists Anonymous.’” It was also very much a boy’s club, such that when a later organization, the Society for Psychical Research, admitted women, Ghost Club members were “spooked,” remarks Tibbott, and became an even more “secretive, select brotherhood (they actually called each other ‘Brother Ghost’).” They finally admitted women in the 20th century.

Despite its secrecy, the club attracted a good deal of attention. It could hardly be otherwise, given the fame of its members. At one time they were reputed by the North British Review, remarks Leo Ruickbie, “to have amassed over 2,000 cases of apparitions.” Their reputation for taking a critical approach preceded members as well. George Cruikshank, Charles Dickens’ illustrator, dedicated his book A Discovery Concerning Ghosts to the Ghost Club, either as a joke, or to “demonstrate the skeptical turn of mind of the Club’s members, for Cruikshank’s slim volume sets out to debunk the whole idea of apparitions.”

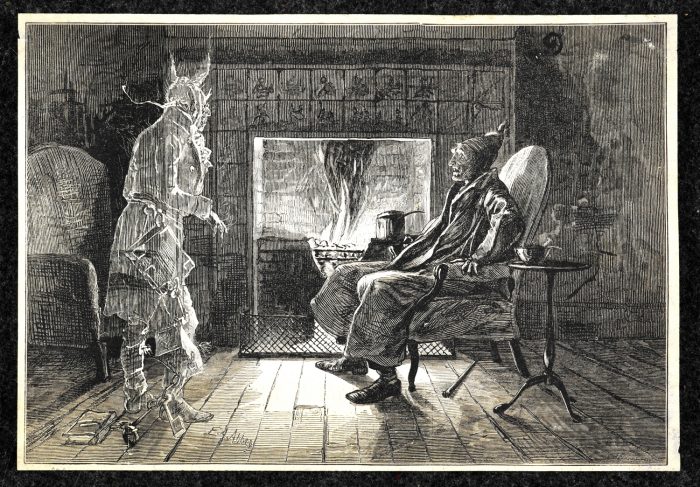

Despite his literary use of spirits as a narrative device (see another of Dickens’ illustrators, American artist E.A. Abbey, interpret the appearance of Jacob Marley’s ghost, above), Dickens himself began and likely ended his tenure in the Ghost club—which he left in 1870—as a skeptic. In 1853, he wrote in an article titled A Haunted House:

That there are on record many circumstantial and minute accounts of haunted houses is well known to most people. But, all such narratives must be received with the greatest circumspection, and sifted with the utmost care; nothing in them must be taken for granted, and every detail proved by direct and clear evidence, before it can be received.

In his 1865 An Unpatented Ghost, Dickens mocked “the commercial tone which has been given to the subject,” and the use of Spiritualism to ensnare the gullible for profit. It is unfortunate that later members did not retain the critical spirit of the club’s most famous founder. Part of the reason for the Ghost Club’s intensified secrecy in its later years has to do with some very bad press. For example, one prominent member—chemist, Royal Society Fellow, and publisher of the Chemical News, Sir William Crookes—announced in 1871 that he had “scientifically measured and tested,” Roger Luckhurst notes, “the existence of a new force in nature, which he called ‘psychic force,’ that he believed was exercised by mediums in séances.”

Crookes reported several sightings of a ghost named “Katie King,” but most people believed he had been duped by his test medium, a teenager named Florence Cook. His “apparent credulity made this one of the great scientific controversies of the age,” and the resulting uproar nearly ruined his business and his credibility. The club’s activities lapsed after Dickens’ departure and the Crookes incident, but was revived in 1882 by clergyman and medium William Stainton Moses, a believer in ghosts, who wrote about the paranormal transmission of spiritual messages through automatic writing.

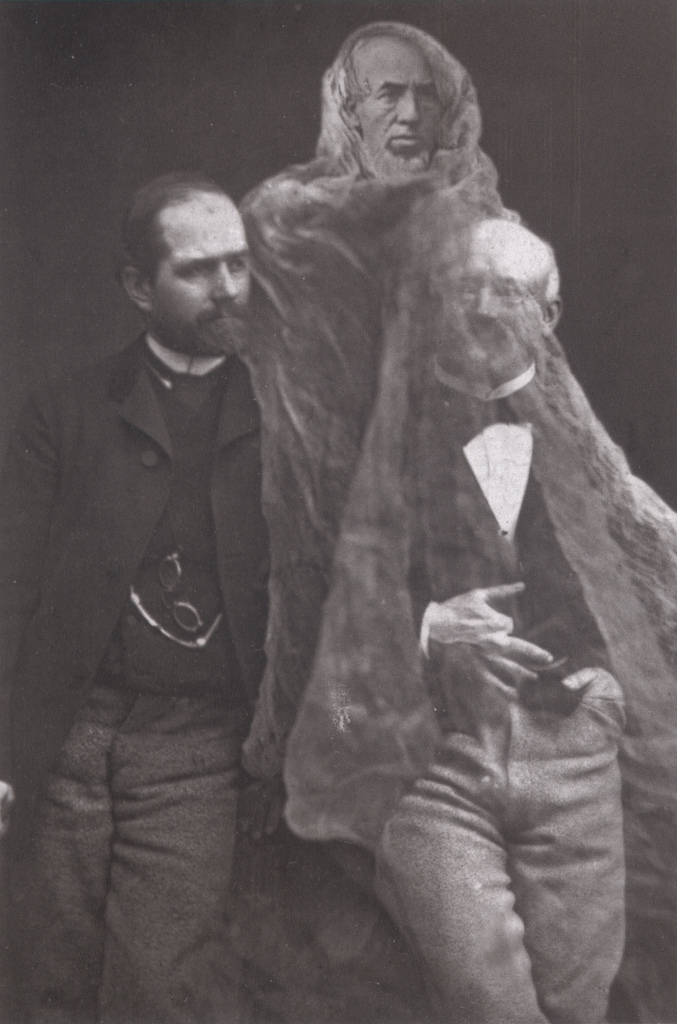

Moses also endorsed the “spirit photography” of Édouard Isidore Buguet, even after Buguet was exposed as a fraud. (See one of Budget’s ghost photos above.) Like many people taken in by hoaxes, Moses refused to believe the truth and doubled down when presented with evidence, speculating that Budget’s confession had been coerced. A similar fate befell another Ghost Club member, Arthur Conan Doyle, who in 1920 fell victim to a hoax perpetrated by two young girls, who convinced him of the existence of fairies with doctored photographs. (We may laugh at these obvious fakes, but then people one hundred years from now will laugh at the photoshopped images that fool so many of us now.)

Despite these embarrassing incidents, the Ghost Club continued to attract those with paranormal research interests, and still continues today, though it is hardly the exclusive gentleman’s club it was in Dickens’ day. Though still based in the UK, the club “has members all over the world.” They invite any “genuinely open-minded, curious” individual, “whether “an interested skeptic, an academic, or scientist” to join the still fascinatingly inconclusive journey into the paranormal.

Related Content:

Browse The Magical Worlds of Harry Houdini’s Scrapbooks

Hear the Voice of Arthur Conan Doyle After His Death

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Fancisco Xavier, one of the world’s most famous mediums, wrote 400 books through automatic writing. Commercial writters would have made a fortune under this impressive number, but Xavier died a humble man, and is one proof that we can communicate with people from the other side