In the 21st century, most of us have tried our hand at making some kind of digital art or another — even if only touching up cellphone photos of ourselves — but imagine the task of producing it 50 years ago. To make digital art before the world had barely heard the term “digital” required access to a mainframe computer, those hugely expensive hulks that filled rooms and printed out reams and reams of paper data, and the considerable technical know-how to operate it.

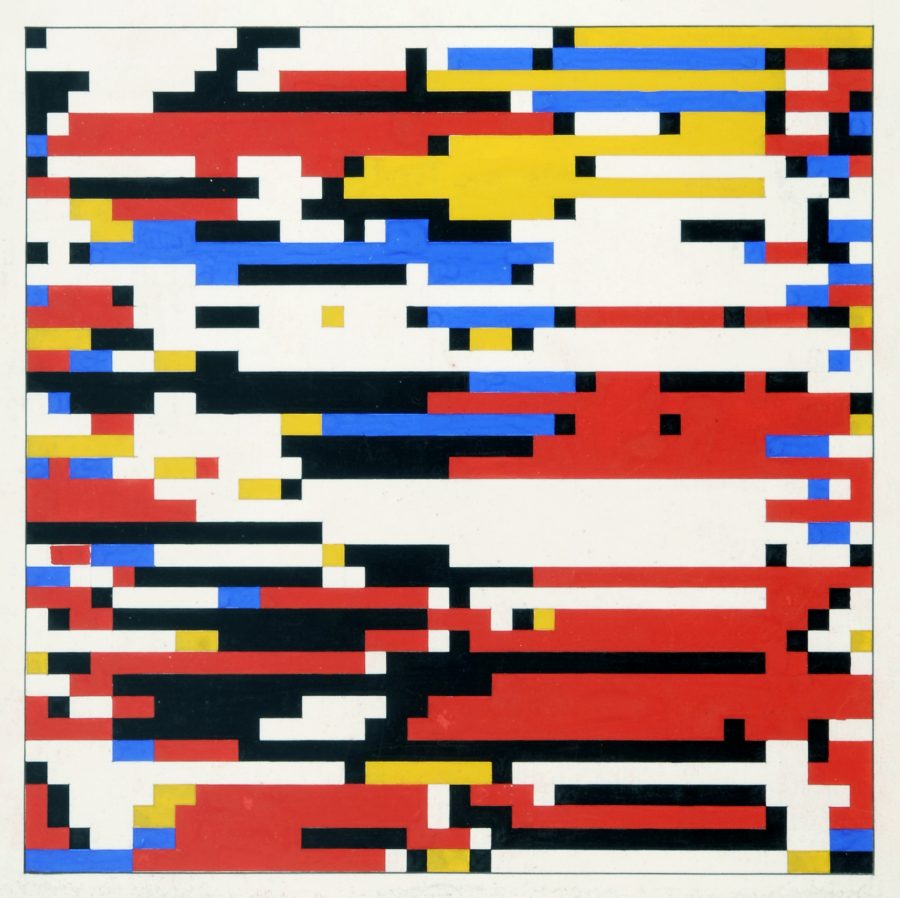

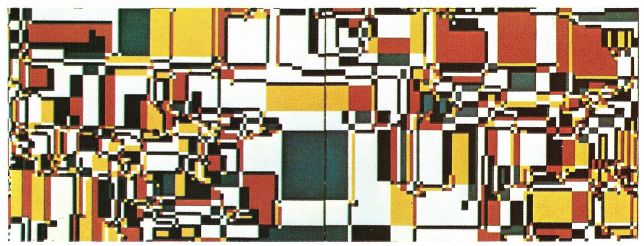

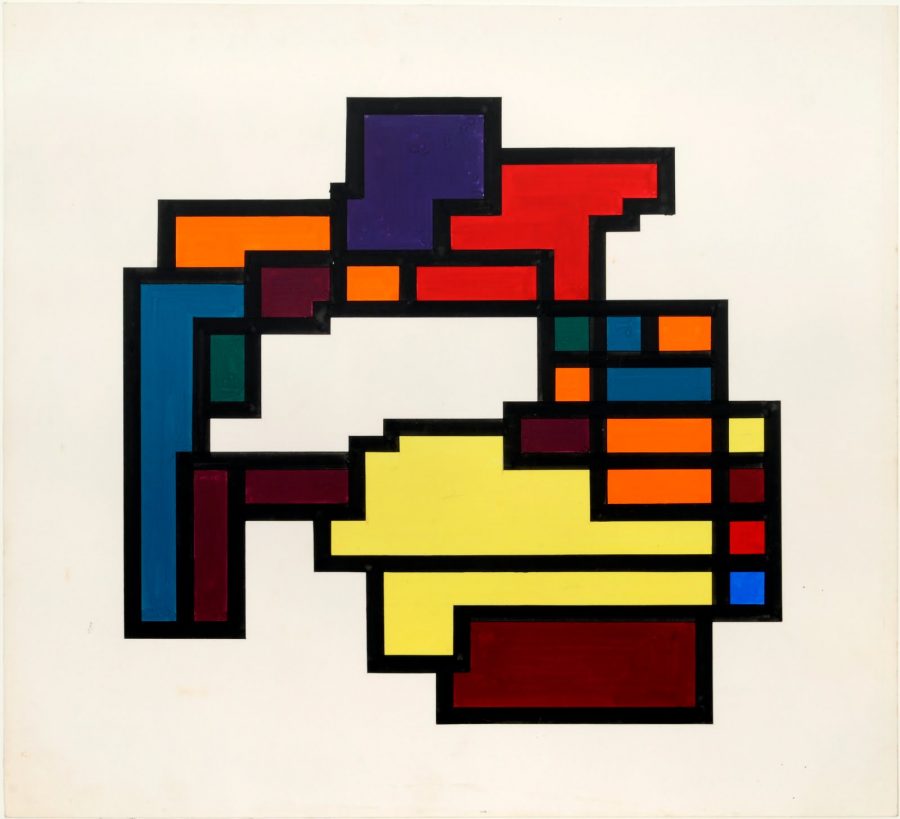

But the achievement also, to go by the very early example of Hiroshi Kawano, required a background in philosophy. A graduate of the University of Tokyo majoring in aesthetics and the philosophy of science before becoming a research assistant at that school and then a lecturer at the Tokyo Metropolitan College of Air-Technology, Kawano marshaled his knowledge and experience to create these “digital Mondrians,” so described because of their computer-generated resemblance to that Dutch painter’s most rigorously angular, solidly colored work.

Kawano had drawn inspiration, according to a Deutsche Welle article on his donation of his archives to Germany’s Center for Media Art, from “the writings of the German philosopher Max Bense, who proposed (among other things) the idea of measuring beauty using scientific rules. At the same time, Kawano heard that scientists were using computers to create music. Putting the two together, he decided to explore the possibility of using a computer to program beauty.”

Doing so required “writing programs in complex computer languages, then laboriously punching these programs into hundreds of cards before feeding them into the machine.” And “while the design of his works produced during the 1960s might look simple — they’re not. They are the result of complex mathematical algorithms programmed so that, although Kawano sets the rules for how the picture could look, he can’t determine exactly what will appear on the printer.”

Just before Kawano passed away in 2012, the ZKM (or Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe), celebrated his pioneering digital art with the exhibition “The Philosopher at the Computer,” some of which you can see in this German-language video clip. “The retrospective emphasizes Kawano’s special role in the circle of pioneers in ‘computer art,’ ” says its introduction. “He was neither artist, who discovered the computer as a new production medium and theme, nor engineer who came to art via the new machine, but a philosopher, who left his desk for the computer center to experiment with theoretical models.”

Can computers create art? Can they even be used to create art? These questions now have practically obvious answers in the affirmative, but back in 1964 when Kawano produced the first of these pieces, working through trial and error with the advice of the curious staff of his university’s computer center, the questions must have sounded impossibly philosophical. Today, writes Overhead Compartment’s Claudio Rivera, Kawano’s digital Mondrians “suggest themselves as an oddly ephemeral transition in the nexus of technology and art. The familiar colors and forms are flash-frozen in crystalline pixelation, almost as if seized up in the final, overheated throes of a suddenly-too-old computer.”

Related Content:

Andy Warhol’s Lost Computer Art Found on 30-Year-Old Floppy Disks

Watch the Dutch Paint “the Largest Mondrian Painting in the World”

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply