Uruguayan-French poet Jules Laforgue, one of the young T.S. Eliot’s favorites, published his major work, The Imitation of Our Lady the Moon, in 1886, two years before his untimely death at 27 from tuberculosis. It is “a book of poems,” notes Wuthering Expectations, “about clowns who live on the moon… wear black silk skullcaps and use dandelions as boutonieres.” The Pierrots in his poems, Laforgue once wrote in a letter, “seem to me to have arrived at true wisdom” as they contemplate themselves and their conflicts in the light of the moon’s many faces.

I cannot help but think of Laforgue when I think of another artist who, around the same time, began on the other side of the world what is often considered the greatest work of his career. The artist, Japanese printmaker Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, also stood astride an old world and a rapidly modernizing new one. And his visual ruminations, though lacking Laforgue’s arch comedy, beautifully illustrate the same kind of dreamy contemplation, loneliness, melancholy, and weary resignation. The moon, as Laforgue wrote—a “Cat’s‑eye of bright / Redeeming light”—both comforts and taunts us: “It comes with the force of a body blow / That the Moon is a place one cannot go.”

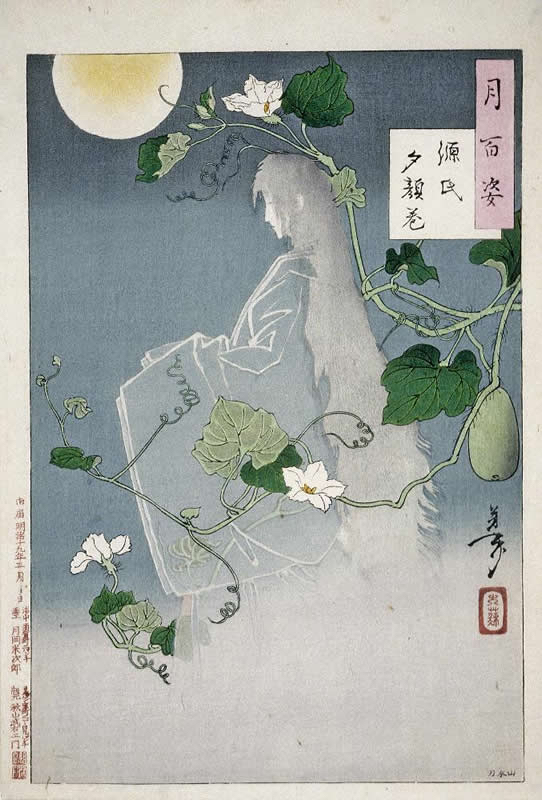

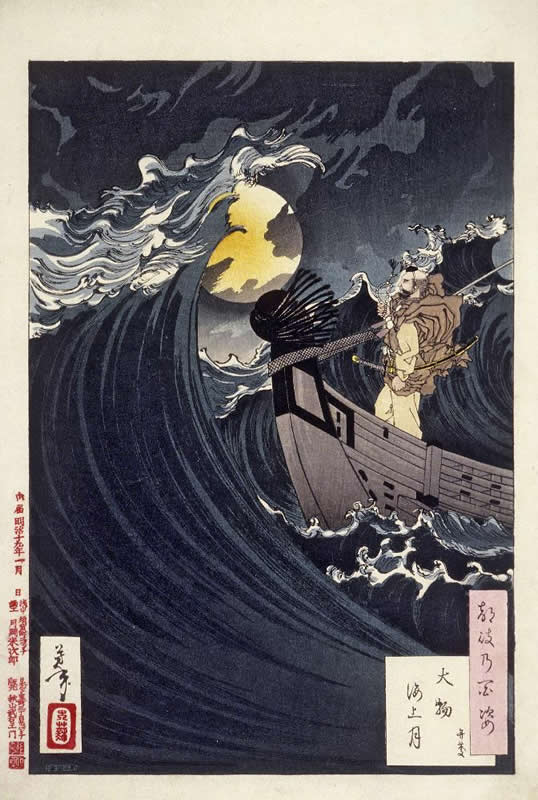

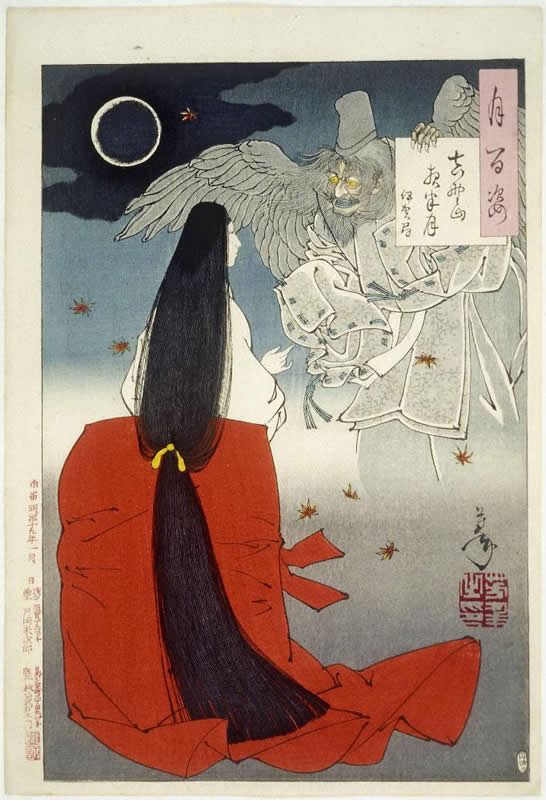

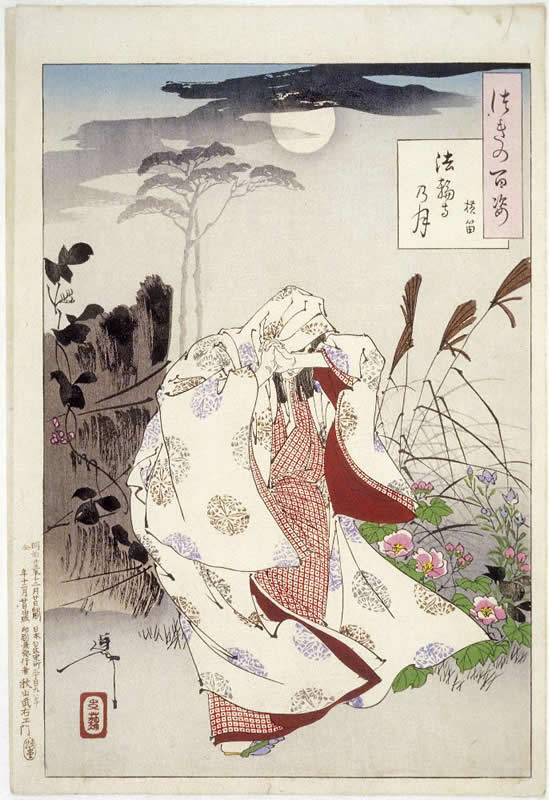

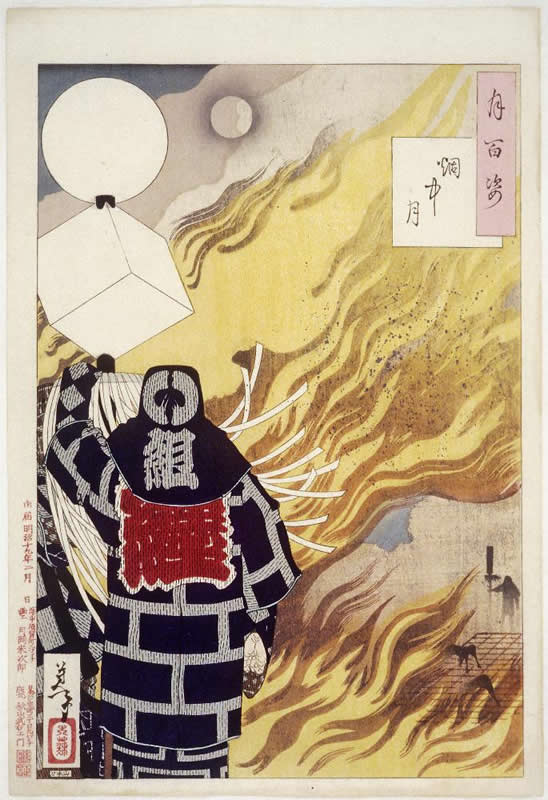

Yoshitoshi’s prints feature a fixation on the moon’s mysteries, and a theatrical device to aid in the contemplation of its meanings: characters from Chinese and Japanese folklore and heroes from novels and plays, all of them staged just after key moments in their stories, in static postures and in silent dialogue with the night. Heavily invested with literary allusions and deeply laden with symbolism, the 100 prints, writes the Fitzwilliam Museum, “conjure a refined poetry to give a new twist to traditional subjects.”

The portraits, mostly solitary, wistful, and brooding, “penetrated deeper into the psychology of his subjects” than previous work in Yoshitoshi’s Ukiyo‑e style, one soon to be altered permanently by Western influences flooding in between the Edo and Meiji periods. Yoshitoshi both incorporated and resisted this influence, using figures from Kabuki and Noh theater to represent traditional Japanese arts, yet introducing techniques “never seen before in Japanese woodblock prints,” writes J. Noel Chiappa, breaking convention by “show[ing] people freely, from all angles,” rather than only in three-quarter view, and by using increased realism and Western perspectives.

Yoshitoshi began publishing these prints in 1885, and they proved hugely popular. People lined up for new additions to the series, which ran until 1892, when the artist died after a long struggle with mental illness. In these last years, he produced his greatest work, which also includes a kabuki-style series based on Japanese and Chinese ghost stories, New Forms of 36 Ghost Stories. “In a Japan that was turning away from its own past,” Chiappa writes, Yoshitoshi, “almost single-handedly managed to push the traditional Japanese woodblock print to a new level, before it effectively died with him.

His tumultuous career, after very successful beginnings, had fallen into disrepair and he had been publishing illustrations for sensationalist newspapers, an erotic portrait series of famous courtesans, and macabre prints of violence and cruelty. These preoccupations become completely stylized and psychologized in his final works, especially in One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, an extraordinary series of prints. View them all, with short descriptions of each subject, here, or at the Ronin Gallery, who provide information on the size and condition of each of its prints and allow viewers to zoom in on every detail. The images have also been publishished in a 2003 book, One Hundred Aspects of the Moon: Japanese Woodblock Prints by Yoshitoshi.

While it certainly helps to understand the literary and cultural context of each print in the series, it is not necessary for an appreciation of their exquisite visual poetry. Perhaps the artist’s memorial poem after his death at age 53 provides us with a master key for viewing his One Hundred Aspects of the Moon.

holding back the night

with increasing brilliance

the summer moon

Related Content:

Download Hundreds of 19th-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints by Masters of the Tradition

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

These pictures are really beautiful.

Thank you for a beautiful web site