One of the greatest challenges for writers and greatest joys for readers of fantasy and science fiction is what we call “world building,” the art of creating cities, countries, continents, planets, galaxies, and whole universes to people with warring factions and nomadic truth seekers. Such writing is the natural offspring of the Medieval travelogue, a genre once taken not as fantasy but fact, when sailors, crusaders, pilgrims, merchants, and mercenaries set out to chart, trade for, and convert, and conquer the world, and returned home with outlandish tales of glittering empires and people with faces in their chests or hopping around on a single foot so big they could use it to shade themselves.

One of the most famous of such chroniclers, Sir John Mandeville, may now be mostly forgotten, but for centuries his Travels was so popular with aspiring navigators and literary men like Shakespeare, Milton, and Keats that “until the Victorian era,” writes Giles Milton, it was he, “not Chaucer, who was known as ‘the father of English prose.’”

Mandeville, like Marco Polo half a century before him, may have been part adventurer, part charlatan, but in any case, both drew their itineraries, as did later navigators like Columbus and Walter Raleigh, from a very long tradition: the making of speculative world maps, which far predates the early Middle Ages of pilgrimage and thirst for Eastern spices and gold.

In the Western tradition, we can trace world mapmaking all the way back to 6th century B.C.E., Pre-Socratic thinker Anaximander, student of Thales, whom Aristotle regarded as the first Greek philosopher. We have no copy of the map, but we have some idea what it might have looked since Herodotus described it in detail, a circular known world sitting atop an earth the shape of a drum. (Anaximander was also an original speculative astronomer.) His map contained two continents, or halves, “Europe” and “Asia”—which included the known countries of North Africa. “Two relatively small strips of land north and south of the Mediterranean Sea,” with ten inhabited regions in total, that illustrate the very early dichotomizing of the world—in this case divided top to bottom rather than west and east.

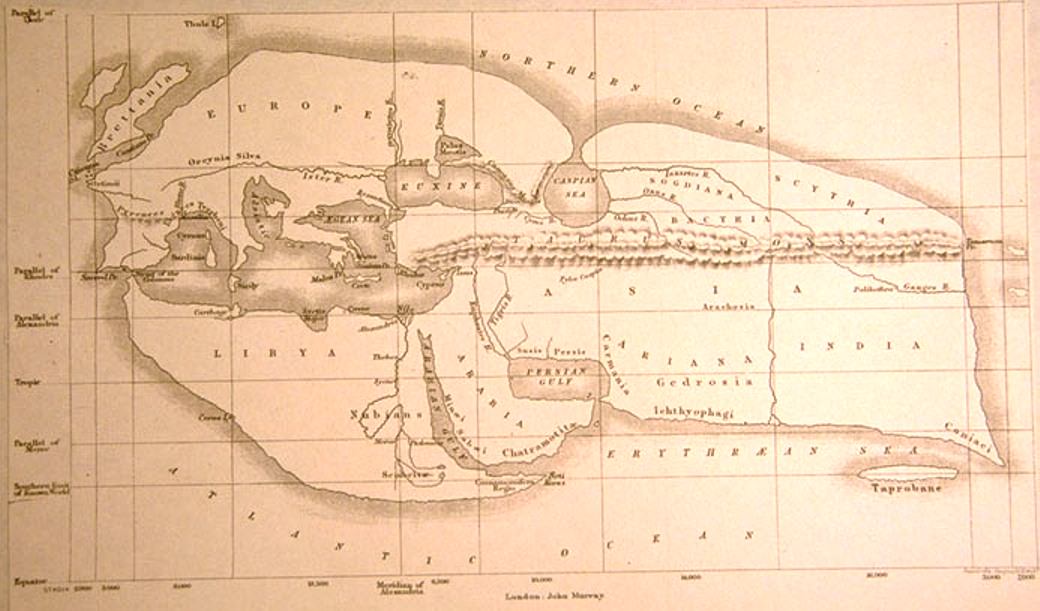

Anaximander may have been the first Greek geographer, but it is the 2nd century B.C.E. that Libyan-Greek scientist and philosopher Eratosthenes who has historically been given the title “Father of Geography” for his three-volume Geography, his discovery that the earth is round, and his accurate calculation of its circumference. Lost to history, Eratosthenes’ Geography has been pieced together from descriptions by Roman authors, as has his map of the world—at the top in a 19th-century reconstruction—showing a contiguous inhabited landmass resembling a lobster claw.

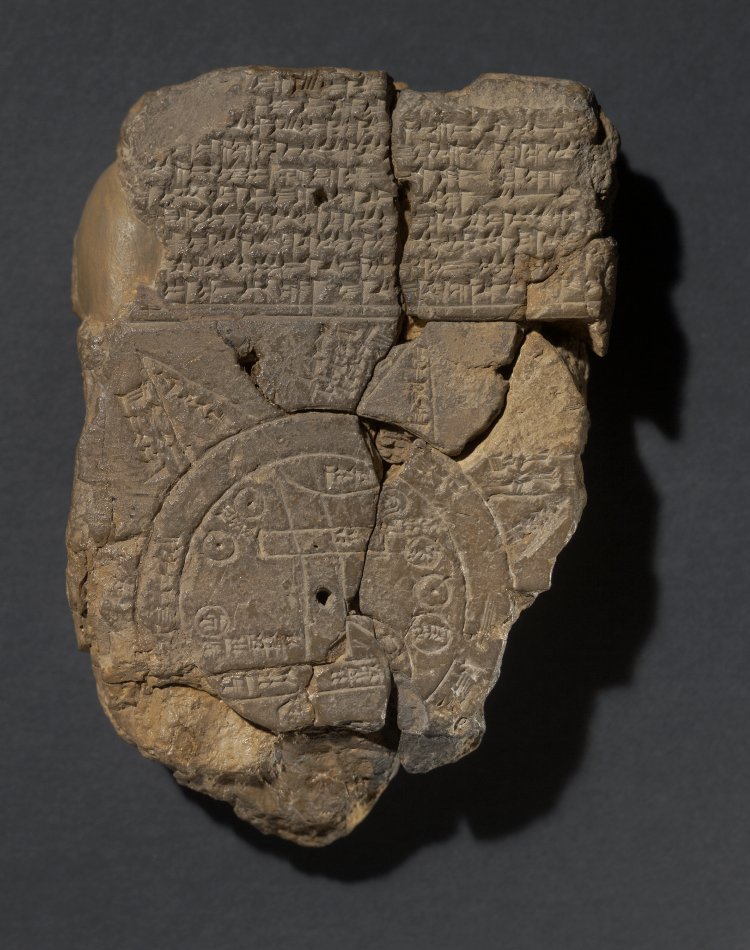

You’ll note that Eratosthenes drew primarily on Anaximander’s description of the world. In turn, his map had a significant influence on later Medieval geographers. A Babylonian world map, inscribed on a clay tablet around the time Anaximander imagined the world (and thought to be the earliest extant example of such a thing), may have influenced European map-making in the age of discovery as well. It depicts a flat, round world, with Babylon at the center (see the British Museum for a detailed translation and commentary of the map’s legend).

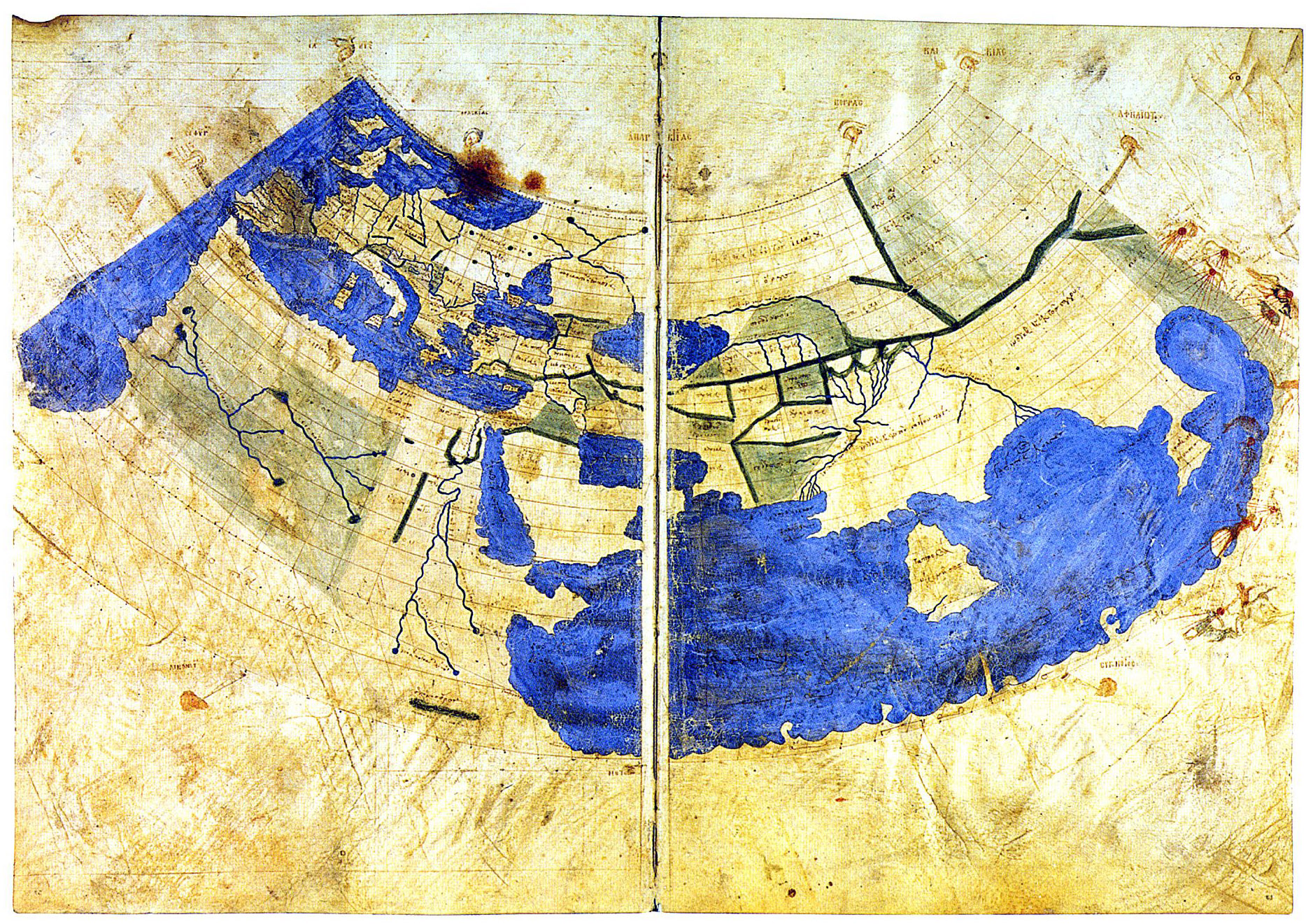

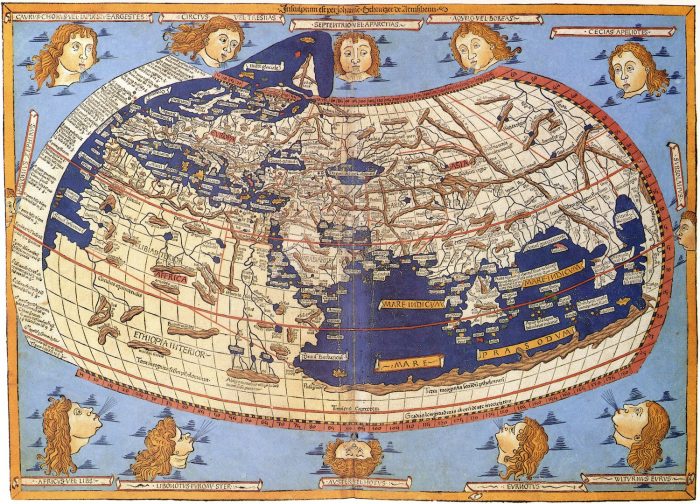

The Babylonian map is said to survive in the similar-looking “T and O map” (third image from top), representing the words orbis terrarium and originating from descriptions in 7th century C.E. Spanish scholar Isadora of Seville’s Etymologiae. The “T” is the Mediterranean and the “O” the ocean. In the version above, a recreation of an 8th century drawing, and every derivation thereafter, we see the three known continents, Asia, Europe, and Africa, with the holy city, Jerusalem, at the center. This map greatly informed early Medieval conceptions of the world, from crusaders to garrulous knights errant like Mandeville, and raconteur merchants like Polo, both of whom made quite an impression on Columbus and Raleigh, as did the circa 1300 map from Constantinople above, the oldest of many drawn from the thousands of coordinates in Roman geographer and astronomer Ptolemy’s Geographia.

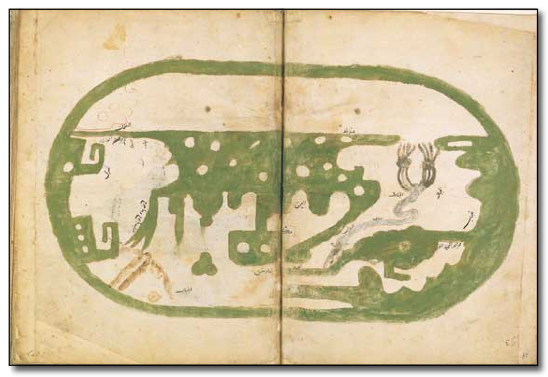

It wouldn’t be until 100 years after the translation of Ptolemy’s text from Greek to Latin in 1407 that his geographical precision became widely known. Until this, “all knowledge of these co-ordinates had been lost in the West,” writes the British Library. This would not be so in the East, however, where world maps like Ibn Hawqal’s, above from 980 C.E., show the influence of Ptolemy, already so long dominant in geography in the Islamic world that it was beginning to wane. Many more world maps survive from 11–12th century Britain, Turkey, and Sicily, from 16th century Korea, and from that wandering age of Columbus and Raleigh, beginning to increasingly resemble the world maps we’re familiar with today. (See a 15th century reconstruction of Ptolemy’s geography below.)

For most of recorded history, knowledge of the world from any one place in it was almost wholly or partly speculative and imaginative, often peopled with monsters and wonders. “All cultures have always believed that the map they valorize is real and true and objective and transparent,” as Jerry Brotton Professor at Queen Mary University of London tells Uri Friedman at The Atlantic. Columbus believed in his speculative maps, even when he ran into islands off the coast of continents charted on none of them. We are still conceptual prisoners—or consumers, users, readers, viewers, audiences—of maps, though we’ve physically plotted every corner of the globe. Perspectives cannot be rendered objective. No gods-eye views exist.

Nonetheless, several culturally formative projections of the world since Ptolemy’s Geography and well before it have changed the whole world, pointing to the power of human imagination and the legendarily imaginative, as well as legendarily brutal, acts of “world building” in real life.

Related Content:

Buckminster Fuller’s Map of the World: The Innovation that Revolutionized Map Design (1943)

“Every Country in the World”–Two Videos Tell You Curious Facts About 190+ Countries

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

I reckon there must be the map collection of “Piri Reis” Ottoman Sailor and expeditionist among the very well known in its contemporaries. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piri_Reis_map