The story of literary modernism in the English-speaking world is most often told through a small collection of Great Works of Art. These poems and novels appeared suddenly after the shock and carnage of World War I, as Europeans and Americans faced the psychological aftermath of mechanized modern combat and its senseless capacity for mass destruction. T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land surveyed the wreckage of European culture and tradition, James Joyce’s Ulysses showed us history as a “nightmare” from which its protagonist is “trying to awake,” Virginia Woolf’s Jacob’s Room showed the modern self as nothing more than a collection of memories and perceptions, emptied of solid existence….

These so-called “high modernist” works all appeared in 1922, when “most scholars consider modernism to be fully fledged.” So writes the Modernist Journals Project (MJP), a joint effort by Brown University and the University of Tulsa, with a number of grants and awards from local sources and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

The project started small in 1996 and has since bloomed into a major resource for scholars and readers. As the MJP’s motto has it, modernism began not with the major works that have come to define it most; “modernism began in the magazines,” small publications with limited readerships that often piqued little interest outside their communities.

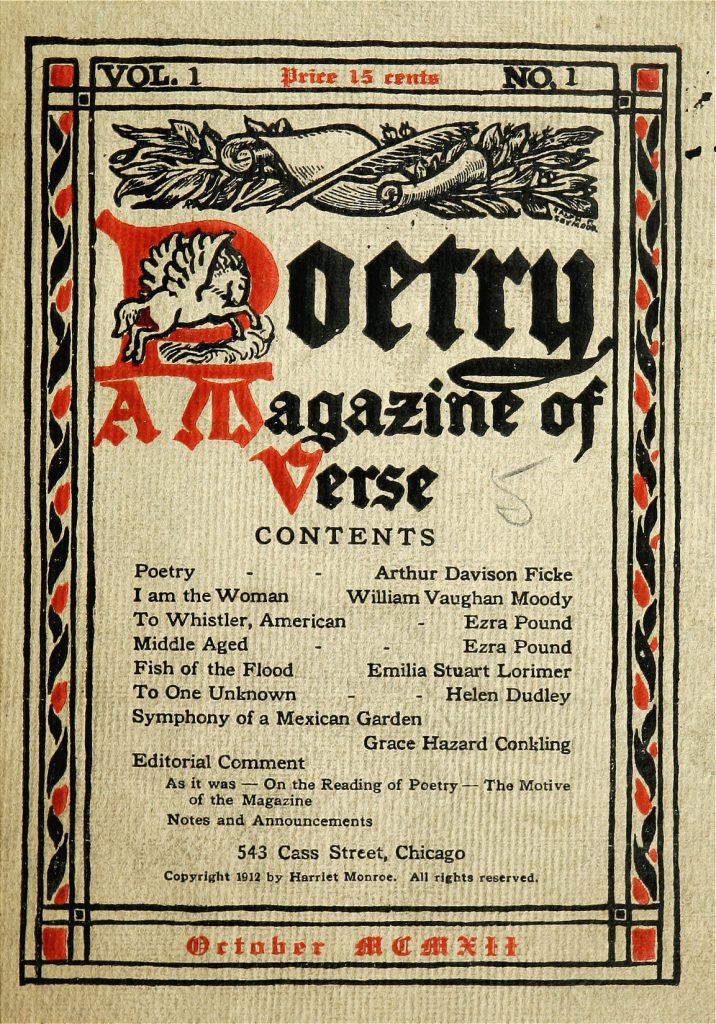

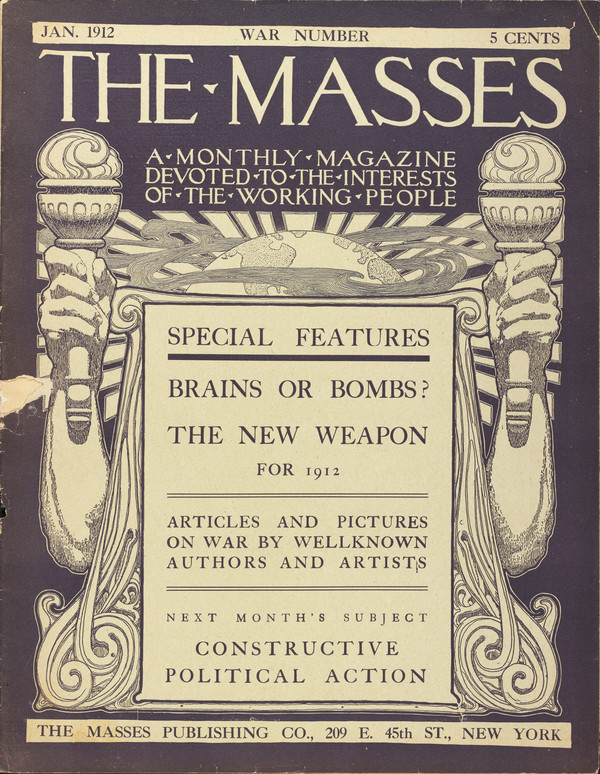

In many of these magazines, such as Harriet Monroe’s Poetry—still around today—we can see bridges between Victorian and modernist poetry. The first issue of Poetry from 1912 (top), for example, features famous Victorian poet William Vaughan Moody next to emerging literary dynamo Ezra Pound, who edited Eliot’s The Waste Land ten years later. Although the exponents of modernism are often divorced from a political context, many modernist writers appeared early in “little magazines” like The Masses, further up, “perhaps the most vibrant and innovative magazine of its day.”

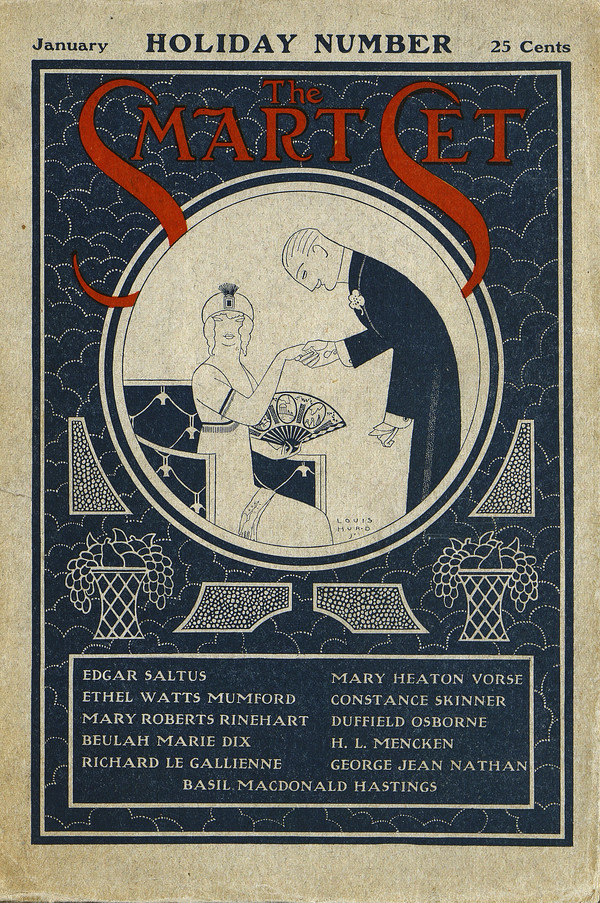

Founded in 1911 as an illustrated socialist monthly, The Masses’ policy was “to do as it Pleases and Conciliate Nobody, not even its Readers.” The magazine published Carl Sandburg, Louis Untermeyer, Amy Lowell, Upton Sinclair, and Sherwood Anderson, among many others. But modernism took root on varied terrain, such that at the same time as The Masses represented major literary change, so too did The Smart Set, founded in 1900 “as a magazine for and about New York’s social elite.” This magazine soon “evolved into something much more important—an expression of popular modernism,” publishing F. Scott Fitzgerald, Joseph Conrad, James Joyce and others.

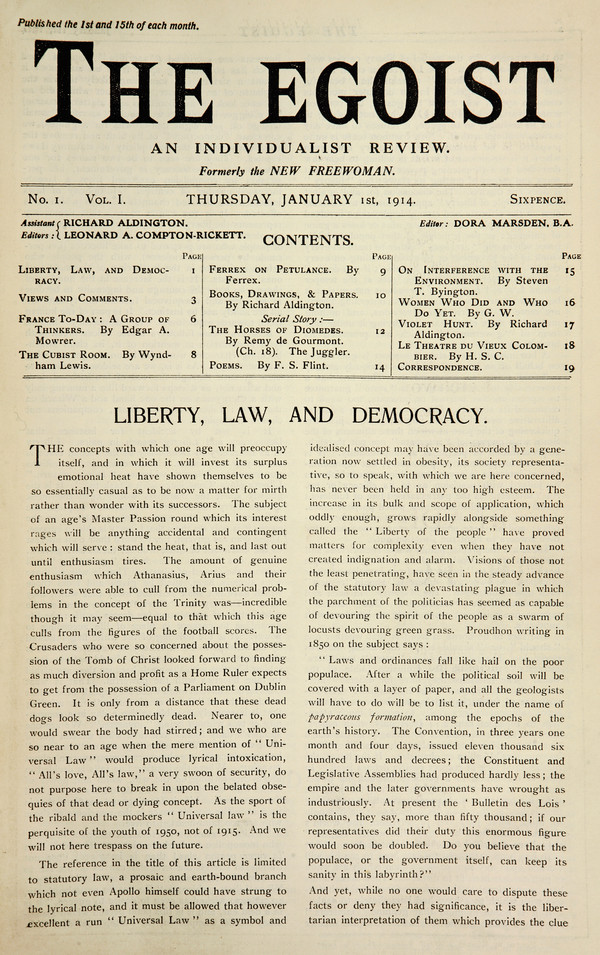

The editorship in 1913 of Willard Huntington Wright “established The Smart Set’s high literary credentials” with figures like Pound and W.B. Yeats. Wright “would up nearly bankrupting the journal” before H.L. Mencken and George Jean Nathan took over the following year. Next to The Smart Set in contemporary importance are magazines like The Egoist, which grew out of an earlier short-lived “weekly feminist review,” The Freewoman.

Begun in 1913 as The New Freewoman by Freewoman editor Dora Marsden, and later edited by Harriet Weaver, The Egoist is only one example of the crucial importance female editors and writers had in bringing literary modernism to fruition. The Egoist eventually took on Eliot as its literary editor and published his seminal essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent.”

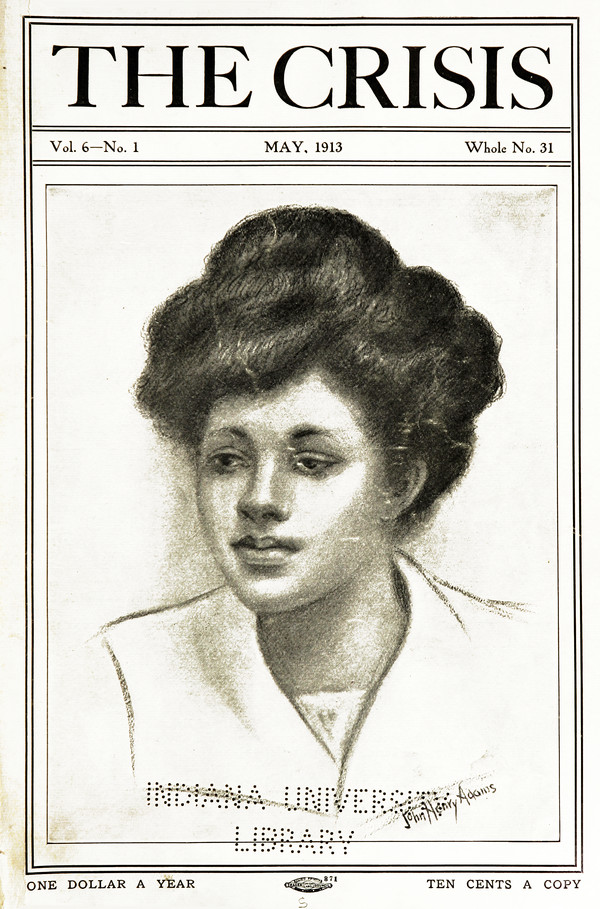

Other publications critical to the growth of modernist literature were The Little Review, Des Imagistes—a series of anthologies organized and edited by Pound—and the W.E.B. Du Bois-edited The Crisis, the NAACP’s official journal, which published work from Jessie Faucet, Charles Chesnutt, Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, Jean Toomer, and many other figures central to the Harlem Renaissance. You’ll find dozens of issues of these and many other modernist journals from the period, represented as scanned images and PDFs at the Modernist Journals Project. At the MJP homepage, you also find biographies of the authors and artists who appear in these journals’ pages, as well as book excerpts and essays about the period of the “little magazines,” when the modernists who became famous in the twenties, and household names decades later, discovered new forms and created new literary communities.

Related Content:

Extensive Archive of Avant-Garde & Modernist Magazines (1890–1939) Now Available Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Noticed Carl Sandburg’s name on a listing above. Can someone here explain why he’s been purged in recent decades from the literary canon? At one time, you could find his writings EVERYWHERE…now, not-so-much.