The life of James Joyce’s schizophrenic daughter Lucia requires no particular embellishment to move and amaze us. The “received wisdom,” writes Sean O’Hagan, about Lucia is that she lived a “blighted life,” as a “sickly second child” after her brother Giorgio. As a teenager, she “pursued a career as a modern dancer and was an accomplished illustrator. At 20, having abandoned both, she fell hopelessly in love with [Samuel] Beckett, a 21-year-old acolyte of her fathers.” He soon ended their one-sided relationship, an incident that may have triggered a psychotic break. Beckett was one of the few people to visit her later in the mental hospital where she died in 1982 after decades of institutionalization.

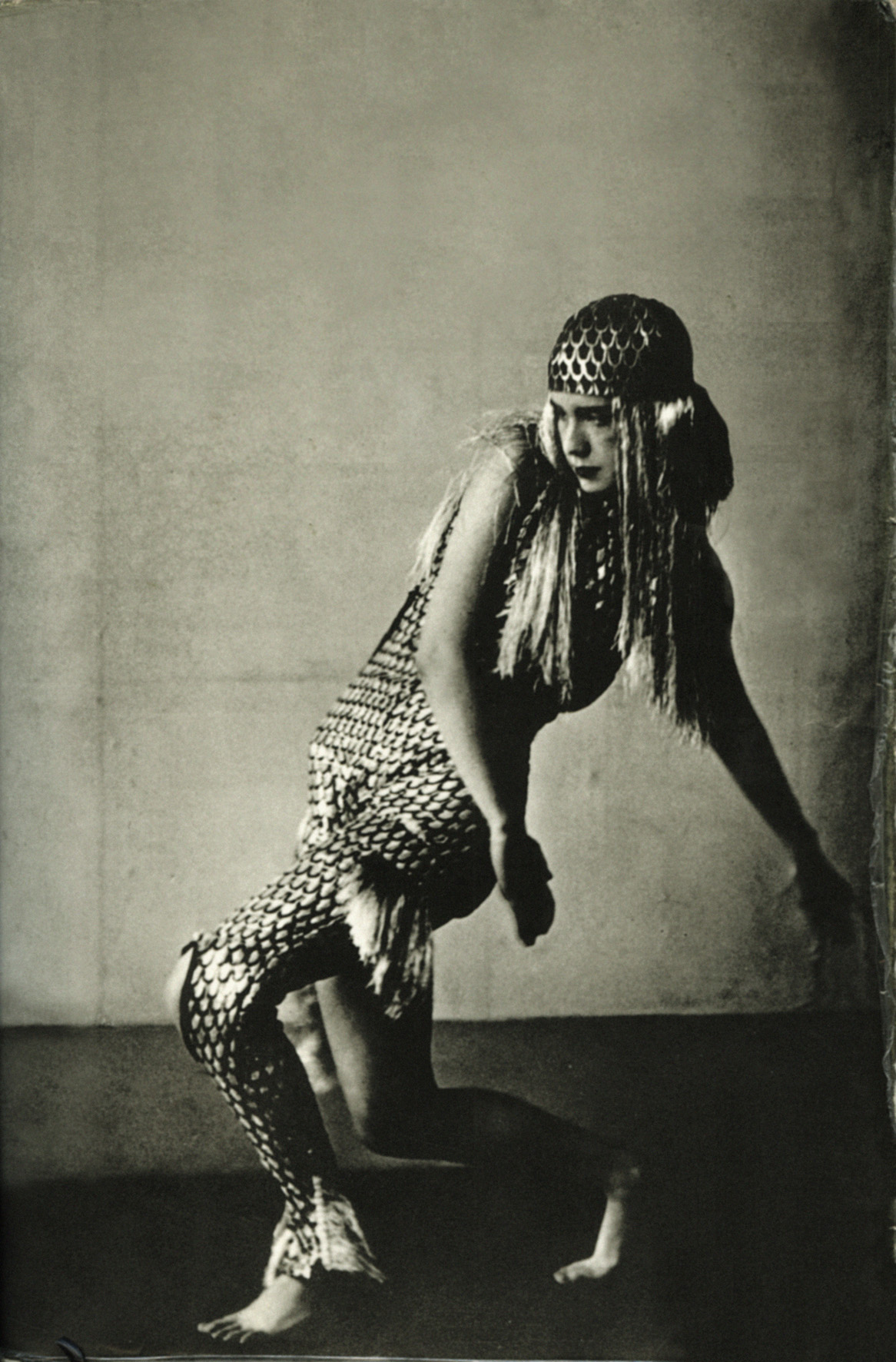

Before succumbing to her illness, Lucia was a highly accomplished artist who worked “with a succession of radically innovative dance teachers,” notes Hermione Lee in a review of a recent biography that “prove[s]… Lucia had talent.” (See her above in Paris in 1929.) Her promise renders her fall that much more dramatic, and her tragedy has inspired variously sensational biographies, plays, a novel and a graphic novel. Lucia also inspired an unflattering portrait in Beckett’s Dream of Fair to Middling Women and, most famously, perhaps provided a model for the language of Finnegans Wake. As Joyce once remarked, “People talk of my influence on my daughter, but what about her influence on me?”

The relationship between father and daughter has provided a subject of disturbing speculation, possibly warranted by Lucia’s “father-fixated… mental agonies,” as Stanford’s Robert M. Polhemus writes, and by “eroticized father-daughter, man-girl relationships” in Finnegans Wake that weave in Freud and Jung “with sexy nymphets on the couches of their secular confessionals.” At least in the excerpt Polhemus cites, Joyce uses the prurient language of psychoanalysis to seemingly express guilt, writing, “we grisly old Sykos who have done our unsmiling bits on ‘alices, when they were yung and easily freudened….”

Without inferring the worst, we can see the rest of this unsettling passage as parody of Jung and Freud’s ideas, of which, Louis Menand writes, he was “contemptuous.” And yet Joyce sent Lucia to see Carl Jung, “the Swiss Tweedledee,” he once wrote, “who is not to be confused with the Viennese Tweedledee.” His daughter’s behavior had become “increasingly erratic,” Lee writes, “she vomited up her food at table; she threw a chair at Nora [Barnacle, her mother] on Joyce’s 50th birthday… she cut the telephone wires on the congratulatory calls that friends were making about the imminent publication of ‘Ulysses’ in America; she set fire to things….”

After a succession of doctors and diagnoses and an “unwilling incarceration,” Jung agreed to analyze her. He had become acquainted with Joyce’s work, having written an ambivalent 1932 essay on Ulysses (calling it “a devotional book for the object-besotted white man”), which he sent to Joyce with a letter. Jung believed that both Lucia Joyce and her father were schizophrenics, but that Joyce, Menand writes, “was functional because he was a genius.” As Jung told Joyce biographer Richard Ellmann, Lucia and Joyce were “like two people going to the bottom of a river, one falling and the other diving.” Jung also, writes Lee, “thought her so bound up with her father’s psychic system that analysis could not be successful.” He was unable to help her, and Joyce reluctantly had her committed.

Much of the relationship between Joyce and his daughter remains a mystery because of the destruction of nearly all of their correspondence by Joyce’s friend Maria Jolas. (Likewise Beckett burned all of his letters from Lucia). This has not stopped her biographer Carol Loeb Shloss from writing about them as “dancing partners,” who “understood each other, for they speak the same language, a language not yet arrived into words….” What is clear is that “Joyce’s art surrounded” his daughter, “haunted her from birth,” and was part of the circumstances that led to her and her brother often living in extreme poverty and instability.

Lucia resented her father but was never able to fully separate herself from him after several failed relationships with other prominent figures, including American artist Alexander Calder. Whether we characterize her story as one of abuse or, as Lee writes of Shloss’ biography (Lucia Joyce: To Dance in the Wake), one of “love and creative intimacy,” depends on what we make of the limited evidence available to us. The erasure of Lucia from her father’s life began not long after his death, and hers “is a story that was not supposed to be told,” writes Shloss. But it deserves to be, as best as it can. Had her life been different, she would doubtless be well-known as an artist in her own right. As one critic wrote of her skills as a performer, linguist, and choreographer in 1928, James Joyce “may yet be known as his daughter’s father.”

Related Content:

Carl Jung Writes a Review of Joyce’s Ulysses and Mails It To The Author (1932)

James Joyce: An Animated Introduction to His Life and Literary Works

When James Joyce & Marcel Proust Met in 1922, and Totally Bored Each Other

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Very interesting article. It is very sad that we still have not made many strides in the fight against mental illness.

A brilliant article. One more example of mental pain suffered by so many and it seems the extraordinarily talented and exceptional souls were and are particularly vulnerable to it.

There is a terrific play by Don Nigro called LUCIA MAD that delves into the Lucia/Beckett relationship with great soaring writing and heartwrenching humor and drama. I directed it in 1998. Well worth the read and I’d like to do it again.

Lucia Joyce is a character in the wonderful new novel Jerusalem by Alan Moore.

I am currently in the midst of Alan Moore’s epic, “Jerusalem” in which the character of Lucia Joyce figures prominently. Particularly in the third chapter of “Vernal’s Inquest,” the third book in the novel, which is written in a “Finnegan’s Wake” style featuring the inner narrative of a day in the life at the asylum where Lucia is committed. The chapter is called, “Round The Bend.”

Fascinating, but depressing. It is as if poor Lucia was a throw away human being of persona non grata after institutionalization, for he rest of her pitiful life. I must find out more and redeem her memory.

The name of the biography is “To Dance in the Wake.” The author is Carol Loeb Shloss. You neglect to mention her first name, and misspell the last (it has no “c”), and never give the title of the book.

Information about Lucia is very scant, and extremely hard to come by. All her letters, the letters of her father to her and all other correspondence by, or about, her has been destroyed. The Schloss biography was widely panned because it’s almost entirely conjecture/opinion/pure imagination. For example, the entire “fable” about Lucia being her father’s muse for “Finnegan’s Wake” is based upon only 2 sightings of Lucia dancing in her father’s presence while he was writing it. But it is true that Lucia’s life was tragic, of that there is no doubt.

This article is distorted and irresponsible, it is based on my biography of Lucia Joyce; it does not name the source…no book title or correct attribution of information. My name is misspelled. And the information is in no way what a reflection of the book in any case. JUng did treat Lucia Joyce, but he was wrong in his diagnosis as well as arrogant in making it. PLease keep stuff like this off the Internet.

William, you are in outer scholastic space. I have all of Lucia’s archives. You might want to read then rather than claim that the book was “panned” …which says that you read and have an opinion bout a review. Wow.

The article headlines treatment, but the text belies that. All that is claimed here is that you involuntary imprisonment only added to her misery.

Thank you for your comments, Carol. This article is not solely drawn on your book but on other sources linked within. Apologies for the misspellings of your last name.

That seems to be the case with many talented people Estelle. It seems as though there could be a fine line between Genius and Eccentricity. One of my Idols seems likely to fall into this category. The beautiful Vincent. His art work is amazing and I have many of his prints on show in tribute to him.