In his introduction to the 2010 essay collection Freud and Fundamentalism, Stathis Gourgouris defines fundamentalism as “thought that disavows multiplicities of meaning, abhors allegorical elements, and strives toward an exclusionary orthodoxy.” While there may be both religious and secular versions of such ideologies worldwide, we can trace the word itself to an Evangelical movement in the U.S., and to a set of beliefs that endures today among around a third of all Americans and has “animated America’s culture wars for over eighty years,” writes David Adams. The fundamentalist movement first took shape in 1920, just as Sigmund Freud wrote and published his Beyond the Pleasure Principle.

It was in that book that Freud introduced the concept of the “death drive.” Adams argues that “the ‘fundamentalist’ and the ‘death drive,’ are twins: they came into being simultaneously,” and “their simultaneity is not merely an accident. Both of these concepts are responding to the profound cultural and psychological crisis resulting from the First World War.” Every calamity since World War I has seemed to reanimate that early 20th century struggle between modernism—with its pluralist values and emphasis on creativity and experiment—and fundamentalism, with its compulsion for rigid hierarchy and destruction. And we might see, as Adams does, such cultural conflicts as analogous to those Freud wrote of between Eros—the pleasure principle—and the drive toward death.

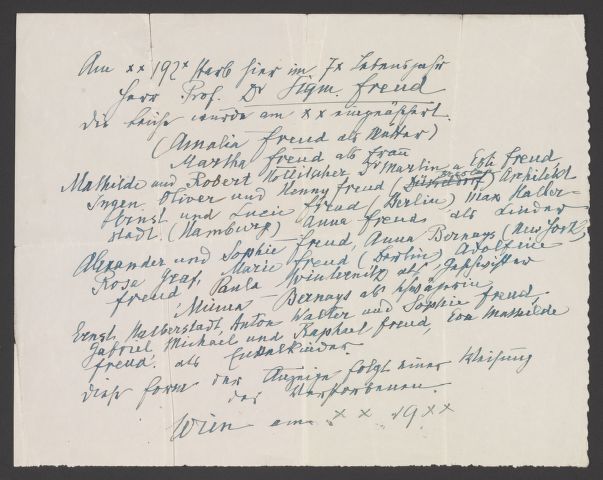

The Great War turned Freud’s thoughts in this direction, as did the racism and anti-Semitism taking hold in both Europe and the U.S. His theory of an instinctual drive toward the destruction of self and others seemed to anticipate the horror of the World War yet to come. Freud integrated the concept into his social theory ten years later in Civilization and its Discontents, in which he wrote that “the inclination to aggression” was “the greatest impediment to civilization.” While meditating on the death instinct as a psychoanalytic and social concept, Freud also pondered his own mortality. Just above, you can see the draft of a death notice that he wrote for himself during the 1920s. This comes to us from the Library of Congress’s new collection of Sigmund Freud papers, which contains artifacts and manuscripts dating from the 6th century B.C.E. (a Greek statue) to correspondence discovered in the late 90s.

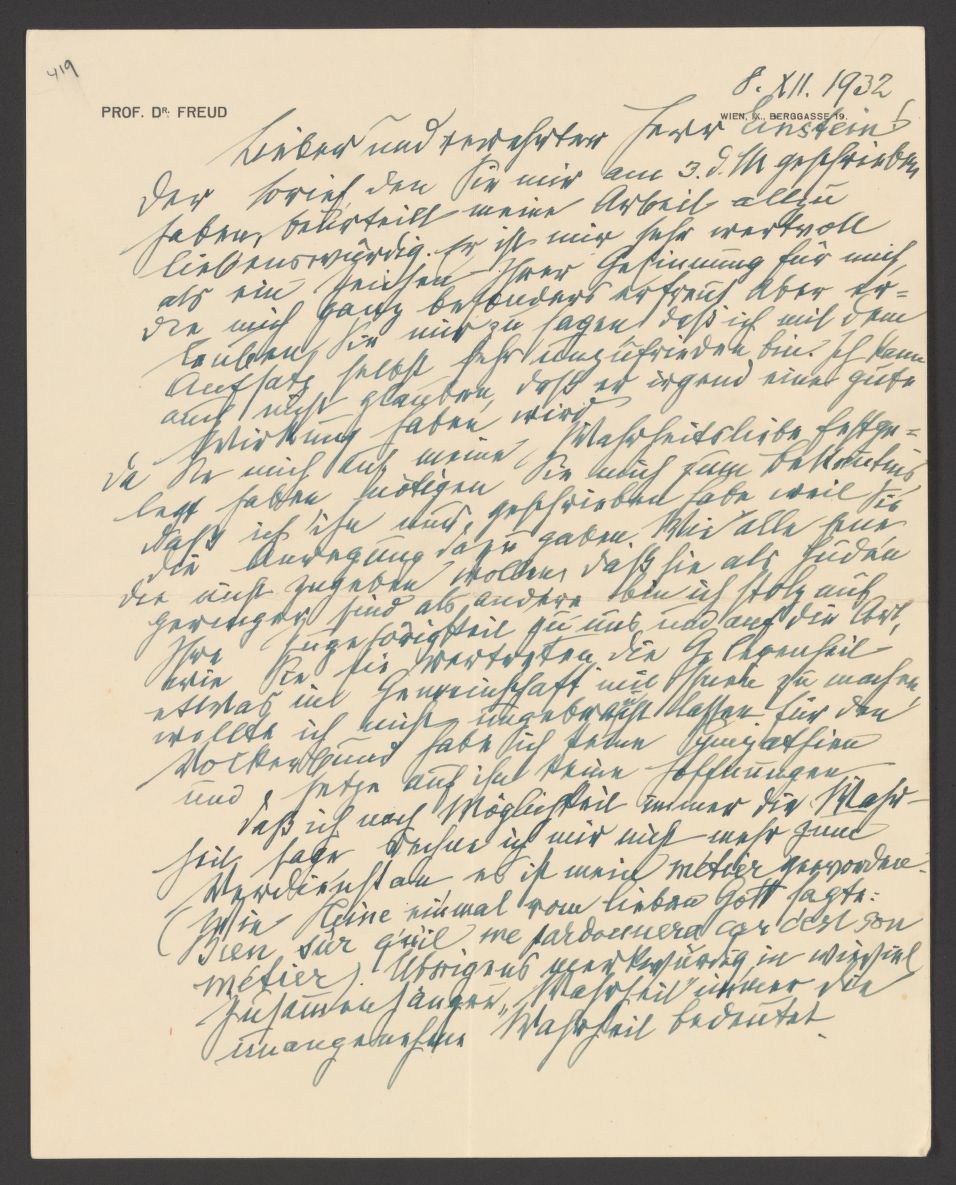

The “bulk of the material,” writes the LoC, dates “from 1891 to 1939,” and the “digitized collection documents Freud’s founding of psychoanalysis, the maturation of psychoanalytic theory, the refinement of its clinical technique, and the proliferation of its adherents and critics.” Much of this archive may be of interest only to the specialist scholar of Freud’s life and work, with “legal documents, estate records… school records” of the Freud children, and other mundane bureaucratic paperwork. But there are also letters representing “nearly six hundred correspondents,” such as Freud’s onetime protégé Carl Jung and Albert Einstein, with whom Freud corresponded in 1932 on the subject of “Why war?” (See Freud’s letter to Einstein above.)

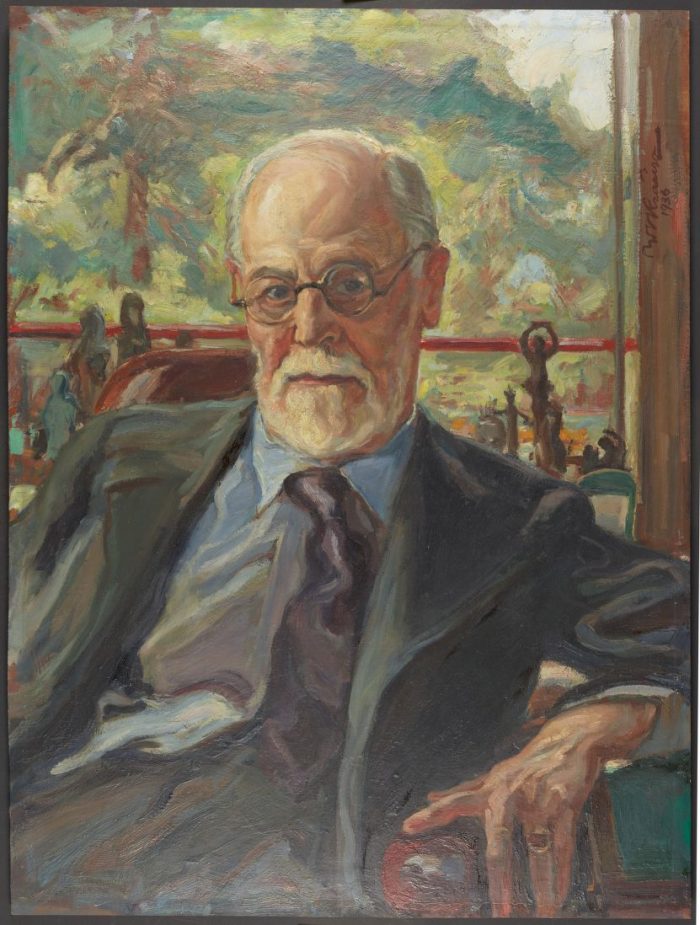

The documents are nearly all in German and the handwritten letters, notes, and drafts will be difficult to read even for speakers of the language. Yet, there are also artifacts like the 1936 portrait of Freud at the top, by Victor Krausz, the pocket notebook Freud carried between 1907 and 1908, just above, and—below—a picture of a pocket watch given to Freud by physician Max Schur, whose family left Austria with Freud’s in 1938. You can browse the online collection of over 20,000 items by date, name, location, and other indices, and all images are downloadable in high resolution scans.

Related Content:

Sigmund Freud Speaks: The Only Known Recording of His Voice, 1938

The Famous Letter Where Freud Breaks His Relationship with Jung (1913)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply