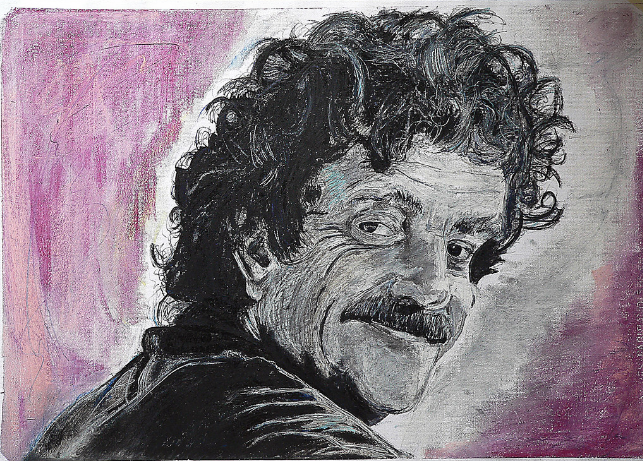

Image by Daniele Prati, via Flickr Commons

Kurt Vonnegut wrote novels, of course, but also short stories, essays, and — briefly, suitably late in his career — correspondence from the afterlife. He did that last gig in 1998, composing for broadcast on the formidable WNYC, by undergoing a series of what he called “controlled near-death experiences” orchestrated, so he claimed, by “Dr. Jack Kevorkian and the facilities of a Huntsville, Texas execution chamber.” These made possible “more than one hundred visits to Heaven and my returning to life to tell the tale,” or rather, to tell the tales of the more permanently deceased with whom he’d sat down for a chat.

Vonnegut’s roster of afterlife interviewees included personages he personally admired such as Eugene Debs (listen), Isaac Newton (listen), and Clarence Darrow (listen), as well as historical villains like James Earl Ray (listen) and Adolf Hitler (listen). Other of the dead with whom he spoke, while they may not qualify as household names, nevertheless went to the grave with some sort of achievement under their belts: Olestra inventor Fred H. Mattson, for instance, or John Wesley Joyce, owner of the famed Greenwich Village literary watering hole The Lion’s Head. Only the Slaughterhouse-Five author’s courageous and impossible reportage has saved the names of a few, like that of retired construction worker Salvatore Biagini, from total obscurity.

Famous or not, people interested Vonnegut, who claimed to get his ideas from “disgust with civilization” but also served as honorary president of the National Humanist Association. This aspect of his personality comes up in the Brian Lehrer Show segment just above, a listen back to Vonnegut’s “Reports on the Afterlife” segments for WNYC’s 90th anniversary. (You can listen to all the segments individually here.)

Producer Marty Goldensohn talks about recording them at Vonnegut’s apartment, where the famous writer would answer the phone every few minutes for a brief talk with one curious fan after another, none of whom he’d taken any pains whatsoever to keep from finding his phone number. “It was a wonderful thing,” says Goldensohn. “He had a way of talking, hearing what he wanted to hear, thanking, and hanging up very nicely. Sixty seconds.” He’d also mastered, adds Lehrer, the art of the one-minute trip to the afterlife, and the stories this unusual radio format allowed him to tell surely drew from the vast range of experiences and emotions to which Vonnegut had exposed his mind not just through reading, but also with such frequent and brief yet very real human connections he’d make on a seemingly near-constant basis.

A little bit less than a decade after these recordings and the subsequent publication of their print collection God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian, the unceasingly smoking and drinking Vonnegut would, at the age of 84, make his own final trip to the afterlife. There he now presumably awaits (possibly beside Kevorkian himself) the next correspondent intrepid enough to come up and interview him. Given the events of the past decade, listeners could certainly use whatever dose of his characteristically clear-eyed and sardonic perspective he might have to offer.

Related Content:

Hear Kurt Vonnegut Read Slaughterhouse-Five, Cat’s Cradle & Other Novels

Hear Kurt Vonnegut’s Very First Public Reading from Breakfast of Champions (1970)

An Animated Kurt Vonnegut Visits NYU, Riffs, Rambles, and Blows the Kids’ Minds (1970)

Kurt Vonnegut Diagrams the Shape of All Stories in a Master’s Thesis Rejected by U. Chicago

In 1988, Kurt Vonnegut Writes a Letter to People Living in 2088, Giving 7 Pieces of Advice

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply