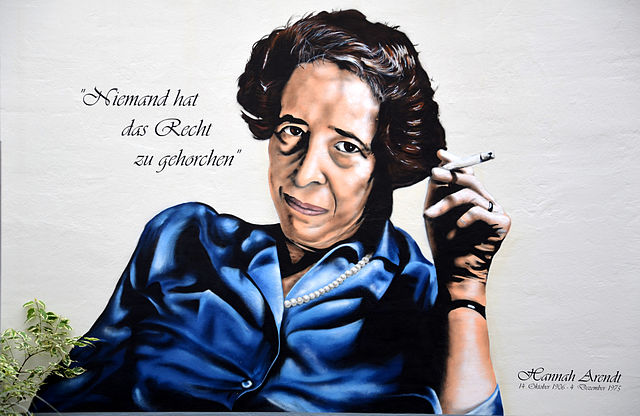

Image by Bernd Schwabe, via Wikimedia Commons

When Eichmann in Jerusalem—Hannah Arendt’s book about Nazi officer Adolf Eichmann’s trial—came out in 1963, it contributed one of the most famous of post-war ideas to the discourse, the “banality of evil.” And the concept at first caused a critical furor. “Enormous controversy centered on what Arendt had written about the conduct of the trial, her depiction of Eichmann, and her discussion of the role of the Jewish Councils,” writes Michael Ezra at Dissent magazine “Eichmann, she claimed, was not a ‘monster’; instead, she suspected, he was a ‘clown.’”

Arendt blamed victims who were forced to collaborate, critics charged, and made the Nazi officer seem ordinary and unremarkable, relieving him of the extreme moral weight of his responsibility. She answered these charges in an essay titled “Personal Responsibility Under Dictatorship,” published in 1964. Here, she aims to clarify the question in her title by arguing that if Eichmann were allowed to represent a monstrous and inhuman system, rather than shockingly ordinary human beings, his conviction would make him a scapegoat and let others off the hook. Instead, she believes that everyone who worked for the regime, whatever their motives, is complicit and morally culpable.

But although most people are culpable of great moral crimes, those who collaborated were not, in fact, criminals. On the contrary, they chose to follow the rules in a demonstrably criminal regime. It’s a nuance that becomes a stark moral challenge. Arendt points out that everyone who served the regime agreed to degrees of violence when they had other options, even if those might be fatal. Quoting Mary McCarthy, she writes, “If somebody points a gun at you and says, ‘Kill your friend or I will kill you,’ he is tempting you, that is all.”

While this circumstance may provide a “legal excuse,” for killing, Arendt seeks to define a “moral issue,” a Socratic principle she had “taken for granted” that we all believed: “It is better to suffer than do wrong,” even when doing wrong is the law. People like Eichmann were not criminals and psychopaths, Arendt argued, but rule-followers protected by social privilege. “It was precisely the members of respectable society,” she writes, “who had not been touched by the intellectual and moral upheaval in the early stages of the Nazi period, who were the first to yield. They simply exchanged one system of values against another,” without reflecting on the morality of the entire new system.

Those who refused, on the other hand, who even “chose to die,” rather than kill, did not have “highly developed intelligence or sophistication in moral matters.” But they were critical thinkers practicing what Socrates called a “silent dialogue between me and myself,” and they refused to face a future where they would have to live with themselves after committing or enabling atrocities. We must remember, Arendt writes, that “whatever else happens, as long as we live we shall have to live together with ourselves.”

Such refusals to participate might be small and private and seemingly ineffectual, but in large enough numbers, they would matter. “All governments,” Arendt writes, quoting James Madison, “rest on consent,” rather than abject obedience. Without the consent of government and corporate employees, the “leader… would be helpless.” Arendt admits the unlikely effectiveness of active opposition to a one-party authoritarian state. And yet when people feel most powerless, most under duress, she writes, an honest “admission of one’s own impotence” can give us “a last remnant of strength” to refuse.

We have only for a moment to imagine what would happen to any of these forms of government if enough people would act “irresponsibly” and refuse support, even without active resistance and rebellion, to see how effective a weapon this could be. It is in fact one of the many variations of nonviolent action and resistance—for instance the power that is potential in civil disobedience.

We have example after example of these kinds of refusals to participate in a murderous system or further its aims. Arendt was aware these actions can come at great cost. The alternatives, she argues, may be far worse.

Related Content:

Hannah Arendt’s Original Articles on “the Banality of Evil” in the New Yorker Archive

Henry David Thoreau on When Civil Disobedience and Resistance Are Justified (1849)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

“follow the rules in a demonstrably criminal regime”

If you’re paying attention, you’ll note that we are ALWAYS in a demonstrably criminal regime. It’s only matters of degree that make one year, one continent, different from the next.

Arendt was talking about consent when refusing or speaking out might be personally dangerous — even fatal. Her view is clear but talking of consent should not be confined to extreme situations. Look rather to the heroic status accorded to whistleblowers while collaborators are tolerated or the “wow” accorded to the person who merely disagrees with the boss.

From 2012 this might interest: https://colummccaffery.wordpress.com/2012/05/03/from-the-cardinal-to-the-chancers-its-time-to-make-integrity-important/

You can tell she didn’t have children. Parents value their children’s lives more than morality. They are ready to suffer and ‘lose their soul’ to save them. I would colaborate with a devil if I had to.

No one’s perfect and thus the system is not perfect and will never be. Though as the level of these imperfections rises, so does the problems. Saying we’re “always in a demonstrably criminal regime” is just to black and white.

At the end of the day, how history repeats itself over and over is how we teach are children. The way they are thought and the virtues that are ingrained in them at a young age could be a direct reflection of how the future might unfold. Though an old dog can also learn new tricks.. but only if it wants to and feels as tho it has to. so negative propaganda is effective on adults.. doesn’t have to be per-meditated.

Social unrest.. no matter what the reason, is a creeping monster that not to many see coming till it’s to late.

In zo een toestand is het moeilijk richting te kiezen . Soms is er geen keuze, staan er voor de deur en sleuren

familieleden mee.. zodat je voor de rest van de huisgenoten toch in de verkeerde richting gaat . Niet

overtuigend maar voor bestwil voor allen . De sociale onrust is een

vretende onzichtbare worm die we meestal té laat door hebben

Today she would be censored by YouTube and Twitter.