The writer David Auerbach once posted a fascinating inquest on left-brained literature, an examination of what he calls “a parallel track of literature that is popular specifically among engineers,” excluding genre fiction (science- or otherwise), with an eye toward “which novels of some notoriety and good PR happen to attract members of the engineering professions.” Favored author names turn out to include Richard Powers, Umberto Eco, Haruki Murakami, William Gibson, Italo Calvino, and Jorge Luis Borges.

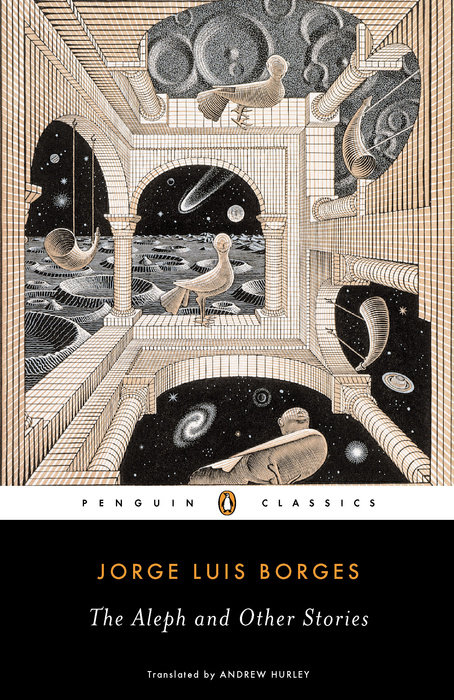

More of these literarily inclined left-brainers exist than one might imagine. From the publisher’s point of view, what cover art could best attract them? Books targeted toward that demographic could do far worse than to use the work of M.C. Escher, who spent his career with one foot in art and the other in mathematics.

In the hitherto unseen (and even unimagined) worlds pictured in his woodcuts, lithographs, and mezzotints, he made use of mathematical concepts from tessellation to reflection to infinity in ways at once impossible and somehow plausible, all of them still intellectually and aesthetically compelling today.

The non-novelist Douglas Hofstadter appears in Auerbach’s inquest since his best-known work, Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid, “which partly uses fictional forms, is too great not to list.” Not only does Escher’s name appear in Hofstadter’s book title, his art informs its central concepts. “Hofstadter wove a network of connections linking the mathematics of Gödel, the art of Escher, and the music of Bach,” writes Allene M. Parker in the paper “Drawing Borges: a Two-Part Invention on the Labyrinths of Jorge Luis Borges and M.C. Escher.” In Gödel, Escher, Bach he describes their common denominator as a “strange loop,” a phenomenon that “occurs whenever, by movement upwards (or downwards) through the levels of some hierarchical system, we unexpectedly find ourselves right back where we started.”

Parker identifies 1948’s “Drawing Hands” as a “particularly striking and familiar example” of a strange loop in Escher’s work. We can interpret that image by recognizing that “it is Escher, the artist, who is drawing both hands and who stands outside this particular puzzle.” Or we can “adopt a Zen-inspired solution and let mystery be mystery by choosing to embrace a unity which contains oppositions,” such as one described by the opening of Borges’ poem “Labyrinths”:

There’ll never be a door. You’re inside

and the keep encompasses the world

and has neither obverse nor reverse

nor circling in secret center.

The Escher-Borges connections go deeper beyond, and as you can see in John Coulthart’s original post, the selection of Escher-covered books extends farther.

Aside from countless nonfiction publications, the Dutch mathematical master’s work has graced science-fiction and fantasy magazines, one edition of Flatland, a collection of “Forteana, weird fiction, occultism and historical speculation,” Clive Barker’s The Damnation Game, and George Orwell’s 1984, a novel more widely read than ever by the left- and right-brained alike. But no matter which hemisphere we favor, Escher — like Orwell, Borges, and Calvino — shows us how to see reality in more interesting ways.

via John Coulthart

Related Content:

Metamorphose: 1999 Documentary Reveals the Life and Work of Artist M.C. Escher

Inspirations: A Short Film Celebrating the Mathematical Art of M.C. Escher

The Cover of George Orwell’s 1984 Becomes Less Censored with Wear and Tear

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply