By the time William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge published their Lyrical Ballads in 1798, poets in England had long been celebrities and arbiters of taste in matters political and literary. The seventeenth century, for example, became known as the “Age of Dryden,” for poet and literary critic John Dryden’s tremendous influence. John Milton, Alexander Pope, Samuel Johnson… these were literary men whose writing vied with the era’s philosophers and advised its nobility and heads of state. By the Romantic period of Wordsworth and Coleridge, no poet held such a position of authority and influence as had those of the previous two centuries.

And yet, we might argue that poetry—and the exalted figure of the poet—became even more sacrosanct and indispensable to British culture throughout the nineteenth century; that poets became, as Percy Shelley wrote in 1821, the “unacknowledged legislators of the world.” Such a hyperbolic statement may seem to conflict with the aims Wordsworth stated for Romantic poetry in the Lyrical Ballads’ preface: “fitting to metrical arrangement a selection of the real language of men in a state of vivid sensation.” Yet when we think of Romantic poetry, we rarely think of the “real language of men.”

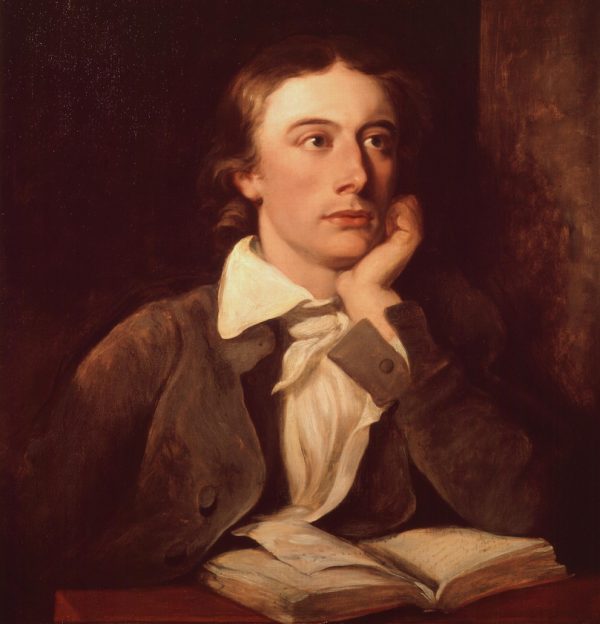

The nineteenth century saw the ascendency of the British Empire to its height during Victoria’s reign. Whether effect or cause of the hubris of the times, both Romantic and Victorian poetry—all the way to the end of Alfred Tennyson’s 12-cycle series Idylls of the King in 1885—gave us mythical epics filled with grandeur of expression and image, and no small amount of bombast. Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (from the Lyrical Ballads) and strange “Kubla Khan” showed the way. Keats tells an outsized tale of the Titans’ fall from Olympus in Hyperion. Shelley gave us the bleak imperial relics of “Ozymandias.”

There were also, of course, the quiet love and nature poems of Wordsworth, Keats, John Clare, and Walter De La Mare, all wonderfully representative of a Romantic pastoral tradition reflecting a nostalgia for a rapidly transforming English countryside. There were the Orientalist poems of exotic wonder, and heroic poems of military valor and revolution. The later nineteenth century revealed even more variety as these strains yielded to greater specialization, and to expanded roles for women poets.

Kipling’s colonialist verses reassured British subjects of their superior status in the scheme of things, and entertained them with fables and morality plays. Oscar Wilde refined the aestheticism of Keats with a decadent eroticism. Brother and sister Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Christina Rossetti took the Romantics’ antiquarianism into the territory of medieval and Gothic revival. Husband and wife Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning looked also to the Middle Ages, and to Italy. Swinburne and Tennyson upheld the tradition of the epic, imbuing it with their own strange preoccupations. Gerard Manley Hopkins did things with language never attempted before.

All of these poets appear in the Spotify playlists here, titled “The Romantics” and “The Victorians,” though you’ll notice that these aren’t mutually exclusive categories. Elizabeth Barrett Browning appears in both lists. Tennyson, perhaps the longest-lived and most famous poet of the age, spans almost the entire century. Keats, whose early tragic death contributed to his rock star status with later readers, died most assuredly a Romantic. But the terms hardly tell us very much by themselves, marking conventional ways of dividing up the literature of the nineteenth century.

What we might notice about the English verse of these two periods on the whole is its tendency toward exaggerated, often florid and overly formal diction and syntax, and its sentimentalism, high seriousness, and decorum. These are qualities we often learn to associate with all poetry, or learn to think of as insincere and pretentious. In the nearly 20 hours of skilled readings here—including some by famous names like James Mason, Dylan Thomas, John Gielgud, Sir Ralph Richardson, Boris Karloff, and Ralph Fiennes—we hear a great deal of nuance, subtlety, irony, and beauty. Learning to appreciate the poetic voices of over a century past not only requires familiarity with unusual idioms and ideas; it also requires tuning our ears to very different kinds of English than our own.

Both playlists will be added to our collection, 1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free.

Related Content:

Stream Classic Poetry Readings from Harvard’s Rich Audio Archive: From W.H. Auden to Dylan Thomas

Rare 1930s Audio: W.B. Yeats Reads Four of His Poems

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

I’m enchanted by your audio collection. Thank you so much.

What does the article suggest about the importance of learning to appreciate the poetic voices of past centuries?

How do the playlists mentioned in the article contribute to making these older poetic works accessible to modern audiences? we have a lot of poetry that’s writed by our students in Tel U