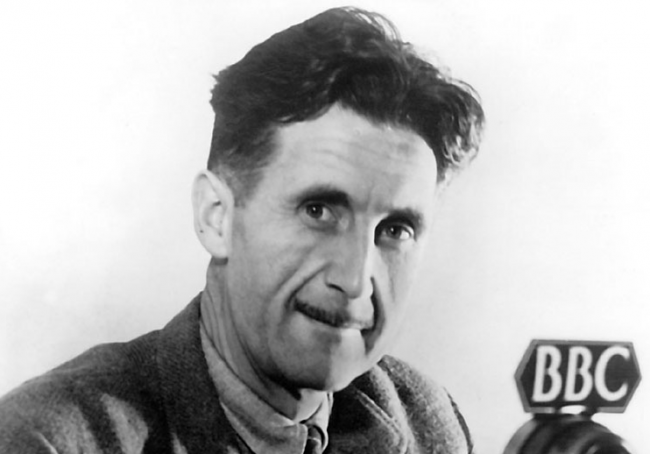

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Two neologisms, “Post-truth” and “Alt-right,” have entered political discourse in this year of turmoil and upheaval, words so notorious they were chosen as the winner and runner-up, respectively, for Oxford Dictionaries’ word of the year. These “Orwellian euphemisms,” argues Noah Berlatsky “conceal old evils” and “whitewash fascism,” recalling “in form and content… Orwell’s old words—specifically some of the newspeak from 1984. ‘Crimethink,’ ‘thoughtcrime,’ and ‘unperson’.… They even sound the same, with their simple, thunk-thunk construction of single syllables mashed together.”

“The sheer ugly clumsiness is supposed to make the language seem futuristic and cutting edge,” Berlatsky writes, “The world to come will be utilitarian, slangy, and up-to-the-minute in its inelegance. So the future was in Orwell’s day; so it is in 2016.” As in Orwell’s day, our current jargon gets mobilized in “defense of the indefensible”—as the novelist, journalist, and revolutionary fighter wrote in his 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language.” And just as in his day, the euphemisms pretty up constant, blatant lying and racist ideologies. We can also draw another linguistic comparison to Orwell’s time: the widespread use of the word “fascism.”

Berlatsky uses the word without defining it (when he talks about “whitewashing fascism”), except to say that “fascism thrives on falsehoods.” That may well be the case, but is it enough of a criterion for an entire political and economic system? The word begs for a cogent analysis. Even Umberto Eco, who grew up under Mussolini’s rule, felt the need for clarity, given that “American radicals,” he wrote in 1995, abused the phrase “fascist pig” as a pejorative for any authority, such that the word hardly meant anything thirty years after World War II.

But surely Orwell—who fought fascism in Spain in 1936, and whose ominous postwar dystopian novels have done more than any literary work to illustrate its menace—could define the word with confidence? Alas, when we look to his work, even before the war had ended, we find him writing, “‘Fascism,’ is almost entirely meaningless.” His short 1944 essay, “What is Fascism?” does not, however, push to abolish the word. He calls instead for “a clear and generally accepted definition of it” against the tendency to “degrade it to the level of a swearword.”

But Orwell (being Orwell) is not optimistic. One reason a definition had been so difficult to come by, he writes, is that any group to whom it is applied would have to make “admissions” most of them are not “willing to make”—admissions as to the real nature of their ideology and objectives, behind the euphemisms, lies, and double-speak. If no one is a fascist, then everyone potentially is. Even in the 40s, Orwell wrote, “if you examine the press you will find that there is almost no set of people—certainly no political party or organized body of any kind—which has not been denounced as Fascist.”

He enumerates those so accused: “Conservatives, Socialists, Communists, Trotskyists, Catholics, War Resisters, Supporters of the war, Nationalists.…” What of the textbook examples just on the other side of the front lines? “When we apply the term ‘Fascism’ to Germany or Japan or Mussolini’s Italy,” Orwell concedes, “we know broadly what we mean.” But appealing to these extreme governments does little good, “because even the major Fascist states differ from one another a good deal in structure and ideology.” Umberto Eco is content to say that fascism adopts the cultural trappings of the nations in which it arises, yet still shares several constant, if contradictory, ideological traits. Orwell isn’t so sure he knows what those are.

So what can Orwell say about the word, one he is eager to hold on to but at a loss to pin down? Though he believes it must name a “political and economic” system as well, Orwell finally opts for an ordinary language definition, to which we “attach at any rate an emotional significance.” Whether we “recklessly fling” the word “in every direction” or use it in more precise ways, we always mean “roughly speaking, something cruel, unscrupulous, arrogant, obscurantist, anti-liberal, and anti-working class. Except for the relatively small number of Fascist sympathizers, almost any English person would accept ‘bully’ as a synonym for ‘Fascist.’” Those today who are not bullies—or unapologetic fascist sympathizers—and who don’t need euphemisms for these words, would likely agree.

You can read “What is Fascism?” here. You can find the short essay published in this volume, The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell.

Related Content:

Umberto Eco Makes a List of the 14 Common Features of Fascism

George Orwell Reviews Mein Kampf: “He Envisages a Horrible Brainless Empire” (1940)

George Orwell Explains in a Revealing 1944 Letter Why He’d Write 1984

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Notice there’s no ‘alt-Left?’ Napoleon the Pig has exempted himself, once again.

Maybe if we approached the meaning at the quantum level say, Schrodinger’s Fascist?

“Notice there’s no ‘alt-Left?”

That’s what the argument is about, no? That perhaps “left” and “right” happily shake hands in the middle when it comes to use of power, as well as the rhetoric they use to conceal it.

I think that we don’t actually have fascism now at all. What we have is indifference, that in effect is some sort of soft authoritarianism. Where populist movements manage to pull off fairly spectacular power-grabs at times from the fact that power is delegated and given away uncritically. While many in power openly, and without contest, argue that the continuation of affairs is the only purpose of the state.

So in many ways we’ve just reverted to a point where Hobbes and Locke both would probably have wondered what the value of their work really would be, when people really pay absolutely no price for just forking over their authority, to a body of power that people don’t think is necessary to control.

What we have now also differs from the scenario in 1984 where it’s actually necessary to maintain the “system” with any amount of cohercion and force. It just exists so we can be lazy and pay no price for it. In fact, you pay a price if you protest. No threat of revolution, no threat of great upheavals, etc. And we’re just stumbling through it, complaining about which side should be allowed to claim the doubleplusgood terms in their rhetoric, while wielding the same unchecked power.

Which also was Aldous Huxley’s critique of Orwell — that he saw 1984 as extremely unlikely, and envisioned a more likely future where people wouldn’t be forced and held by their ears, but would simply float around in blissful soma-induced indifference instead. He was right. Orwell was wrong.

That doesn’t change that Orwell’s explanation on how words we like or dislike lose their meaning very quickly — whether that is “fascism”, “democracy”, “freedom”, and so on — isn’t absolutely spot on.

Surely because they don’t self-identify as Alt-Left?

Wasn’t aware “Alt-left” was in common usage the same way “Alt-right” (Incidentally, a term that many of that persuasion self-identify as) is. There is no marxist analogue to the right wing nationalist movements of today, certainly no movement with popular support, anyhow. The closest thing one can find is a new generation of leftists who identify closest with the social democracy of the postwar period, such as those in Momentum, Podemos and Syriza.

That is one weird mustache George is rocking.

Are not Super Delegate and Electors really euphemisms for fascist overlords?