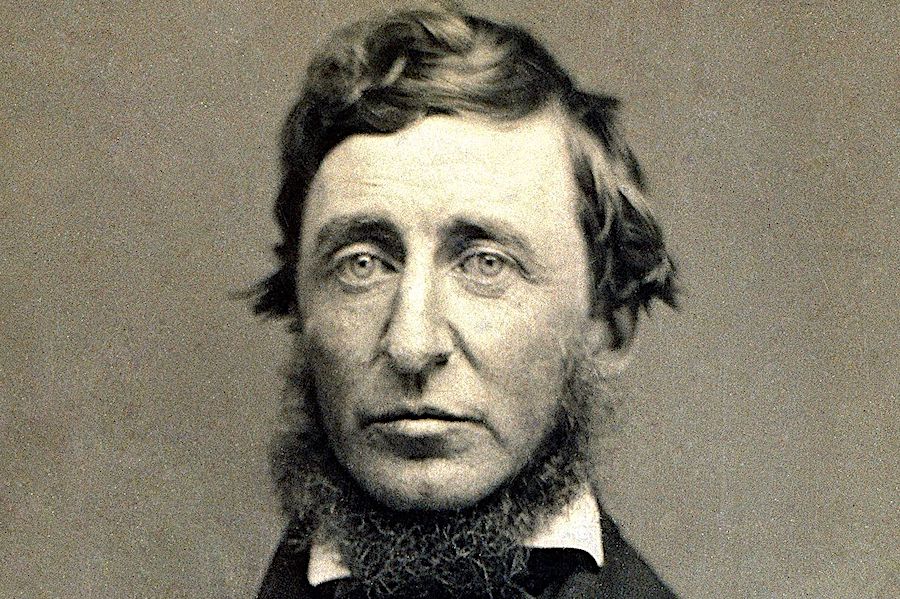

History is rife with examples of oppressive governments. The present is rife with examples of oppressive governments. You can name your own examples. The question that presents itself to any opposition is what is to be done? Go underground? Sabotage? Take up arms? The likelihood of success in such cases—depending on the belligerence of the opposition and the capabilities of the government—varies widely. But I see no moral reason to condemn people for fighting injustice, provided their cause itself is just. Neither, of course, did Henry David Thoreau, author of the 1849 essay “Civil Disobedience,” a document that every student of Political Philosophy 101 knows as an ur-text of modern democratic protest movements.

This is an essay we have become all-too familiar with by reputation rather than by reading. Thoreau’s political philosophy is not passive, as in the phrase “passive resistance.” It is not middle-of-the-road centrism disguised as radicalism. It lies instead at the watering hole where right libertarianism and left anarchism meet to have a drink. “I heartily accept the motto, ‘That government is best which governs least,’” wrote Thoreau, and ultimately “’That government is best which governs not at all.’”

Like many utopian theorists of the 19th century, Thoreau saw this as the inevitable future: “when men are prepared for it, that will be the kind of government they will have.” Thoreau laments all restrictions on trade and regulations on commerce. He also denounces the use of a standing army by “a comparatively… few individuals.” And yet—despite these radical positions—Thoreau has been enshrined in the history of political thought both for his radical tactics and his defense of preserving government, for the present.

“To speak practically and as a citizen,” he wrote, “unlike those who call themselves no-government men, I ask for, not at once no government, but at once a better government.” He does not go to great lengths, as classical philosophers were wont, to define the ideal government. It is radically democratic, that we know. But as to what constitutes injustice, Thoreau is clear:

When the friction comes to have its machine, and oppression and robbery are organized, I say, let us not have such a machine any longer. In other words, when a sixth of the population of a nation which has undertaken to be the refuge of liberty are slaves, and a whole country is unjustly overrun and conquered by a foreign army, and subjected to military law, I think that it is not too soon for honest men to rebel and revolutionize. What makes this duty the more urgent is the fact that the country so overrun is not our own, but ours is the invading army.

This people must cease to hold slaves, and to make war on Mexico, though it cost them their existence as a people.

The figure he cites of “a sixth of the population” is not erroneous. As W.E.B. Du Bois showed in one of his revolutionary 1900 sociological visualizations, during the time of Thoreau’s essay, one-sixth of the country’s population was indeed comprised of people of African descent, most of them enslaved. Thoreau wrote during debates over the impeding Fugitive Slave Act, a law that put every person of color in the expanding country—free or escaped, in every state and territory—at risk of enslavement or imprisonment without any due process.

Thoreau found both this developing nightmare and the Mexican-American war too intolerably unjust for the country to bear. And he recognized the limitations of elections to resolve them: “All voting is a sort of gaming… with a slight moral tinge to it,” he wrote, then observed with devastating irony, given total disenfranchisement of people who were property, that “Only his vote can hasten the abolition of slavery who asserts his own freedom by his vote.”

“Unjust laws exist,” writes Thoreau, “I say, break the law. Let your life be a counter-friction to stop the machine. What I have to do is to see, at any rate, that I do not lend myself to the wrong which I condemn.” Thoreau had put his dicta into practice already many years before. He had stopped paying his poll tax in 1842 to protest the war and the expansion of slavery. He was finally arrested and jailed for the offense in 1846. The incident hardly sparked a movement. He was bailed out, perhaps by his aunt, the following day. And as we well know, the Mexican-American war and the crisis of slavery were both resolved with… war.

But Thoreau used his experience as the basis for “Civil Disobedience,” which he wrote to a local audience in his home state of Massachusetts, and which went on to directly inspire the massively successful, national grassroots movements of Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr. and other non-violent Human Rights and Anti-War leaders around the world. So what did he recommend dissenters do? Here are the basics of his prescriptions, with his words in quotes:

“I do not hesitate to say, that those who call themselves Abolitionists should at once effectually withdraw their support, both in person and property, from the government of Massachusetts.” Thoreau then goes on to describe his particular form of resistance, the non-payment of tax. His thesis here, however, allows for any just refusals to recognize government authority.

“Under a government which imprisons any unjustly, the true place for a just man is also in prison.” Thoreau himself suffered little, it’s true, but millions who came after him—dissidents on all continents save Antarctica—have endured imprisonment, beating, and death. “Suppose blood should flow,” writes Thoreau, “Is there not a sort of blood shed when the conscience is wounded?” As for the justness of disobedience, Thoreau makes a very logical case: “If a thousand men were not to pay their tax-bills this year, that would not be a violent and bloody measure, as it would be to pay them, and enable the State to commit violence and shed innocent blood.”

Thoreau goes on to introduce a good deal of nuance into the argument, writing that community taxes supporting highways and schools are ethical, but those supporting unjust war and enslavement are not. He recommends discerning, thoughtful action. And he expected that the poor would undertake most of the resistance, because the burdens fell heaviest on them, and “because they who assert the purest right, and consequently are the most dangerous to a corrupt State, commonly have not spent much time in accumulating property.” This has generally, throughout history, been true.

The best thing a person of means can do, he writes, is “to endeavor to carry out those schemes which he entertained when he was poor.” Or, presumably, if one has never been so, to follow the poors’ lead. The paradox of Thoreau’s assertion that the least powerful present the greatest threat to the State resolves in his recognition that the State’s power rests not in its appeal to “sense, intellectual or moral” but in its “superior physical strength.” By simply refusing to yield to threats, anyone—even ordinary, powerless people—can deny the government’s authority, “until the State comes to recognize the individual as a higher and independent power, from which all its own power and authority are derived.”

Read Thoreau’s complete essay, “Civil Disobedience,” here.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Enjoy your website.

Thank you for your support