How does censorship come about in advanced, ostensibly democratic societies? In some cases, through institutions colluding in ways that go unnoticed by the general public. As Noam Chomsky has argued for decades, state agencies often collude with the press to spread certain narratives and suppress others. And as we see during Banned Books Week, legislatures, courts, and educational institutions often collude with publishers, teachers, and parents to suppress literature they view as threatening. One such case remains particularly ironic given the book in question: Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, the story of a dystopian society in which all books are banned, and fire departments burn contraband copies.

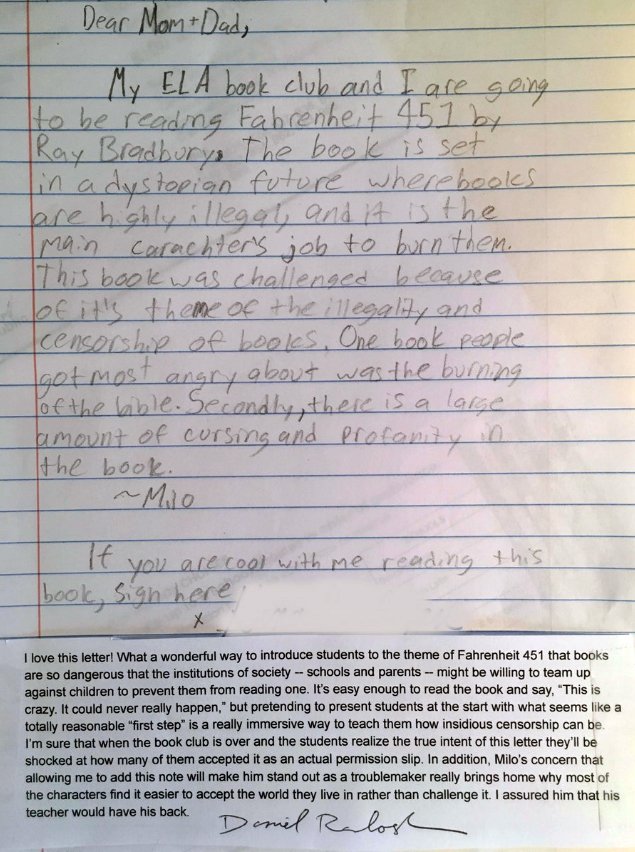

Between the years 1967 and 1979, Ballantine published an expurgated version of the novel for use in high schools, removing content deemed objectionable. Bradbury was completely unaware. For six of those years, the bowdlerized version was the only one sold by the publisher. We can remember this case when we read the response of writer Daniel Radosh to a permission slip his son Milo brought home from his 8th grade teacher for a book club reading of Fahrenheit 451. Written in Milo’s own hand, the initial note, at the top, informs Mr. Radosh that the novel “was challenged because of it’s [sic] theme of the illegality and censorship of books. One book people got most angry about was the burning of the bible. Secondly, there is a large amount of cursing and profanity in the book.”

After this confession, Milo’s note asks for a parental signature in a postscript. Addressing the letter’s true writer, Milo’s teacher, Daniel Radosh responded thus, in the typed note attached to his son’s letter.

I love this letter! What a wonderful way to introduce students to the theme of Fahrenheit 451 that books are so dangerous that the institutions of society – schools and parents – might be willing to team up against children to prevent them from reading one.

It’s easy enough to read the book and say, ‘This is crazy. It could never really happen,’ but pretending to present students at the start with what seems like a totally reasonable ‘first step’ is a really immersive way to teach them how insidious censorship can be.

I’m sure that when the book club is over and the students realise the true intent of this letter they’ll be shocked at how many of them accepted it as an actual permission slip.

In addition, Milo’s concern that allowing me to add to this note will make him stand out as a troublemaker really brings home why most of the characters find it easier to accept the world they live in rather than challenge it.

I assured him that his teacher would have his back.

Radosh’s insinuation that the letter his son was induced to write is not an “actual permission slip” underscores his claim that the exercise is really a means of controlling children by means of collusion, even though, he jests, such a thing must be part of the lesson itself. Should he be allowed to read the novel, the signing and delivery of the permission slip, Radosh devastatingly suggests, completes Milo’s humiliation, bringing home to him “why most of the characters” in the book remain passive, and “find it easier to accept the world they live in rather than challenge it.”

In short, Radosh’s response, for all its pithy irony, digs deeply into the mechanisms that suppress speech deemed so “dangerous that the institutions of society—schools and parents—might be willing to team up against children to prevent them” from reading it.

See Metro UK for a complete transcription of both letters.

via Vintage Anchor

Related Content:

Hear Ray Bradbury’s Classic Sci-Fi Story Fahrenheit 451 as a Radio Drama

The Cover of George Orwell’s 1984 Becomes Less Censored with Wear and Tear

Frank Zappa Debates Censorship on CNN’s Crossfire (1986)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Didn’t Bradbury maintain that the theme was about the influence of TV turning people away from literature and numbing their brains rather than censorship?

Either way, a great book.

obviously “Rob” didn’t read the book.

Yes, there is a strong element in the novel of characters losing their ability to think for themselves because they are addicted to screens.

I read Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 in Elementary School. I think I was 11 or 12 years old, and I loved any book or story by Mr. Bradbury. Maybe this book was never banned in Canada (where I live) because it was just sitting there on the library shelf with many other Bradbury books. I saw the movie on TV when I was around 15, but I preferred Bradbury’s book. The father’s letter in the above article was great.

Well, he read something.

“Ray Bradbury Reveals the True Meaning of Fahrenheit 451: It’s Not About Censorship, But People “Being Turned Into Morons by TV”

http://www.openculture.com/2017/08/ray-bradbury-reveals-the-true-meaning-of-fahrenheit-451.html

Obviously “Gesster” had no interest in Ray Bradbury.

Fahrenheit 451 was not banned in Canada. My Grade 12 Literature course studied it in 1972–73 — along with Sinclair Lewis’s Babbit, and John Wyndham’s The Chrysalids.