The great Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza, it is said, drew his conceptions of god and the universe from his work as an optician, grinding lenses day after day. He lived a life singularly devoted to glass, in which his “evenings to evenings are equal.” So wrote Jorge Luis Borges in a poetic appreciation of Spinoza, of which he later commented, “[Spinoza] is polishing crystal lenses and is polishing a rather vast crystal philosophy of the universe. I think we might consider those tasks parallel. Spinoza is polishing his lenses, Spinoza is polishing vast diamonds, his ethics.”

The polishing of lenses, and work in optics generally, has a long philosophical pedigree, from the experiments of Renaissance artists and scholars, to the natural philosophers of the Scientific Revolution who made their own microscopes and pondered the nature of light. Over a century after Spinoza’s birth, polymath artist and thinker Johann Wolfgang von Goethe published his great work on optics, just one of many directions he turned his gaze. Unlike Spinoza, Goethe had little use for concepts of divinity or for systematic thinking.

But unlike many freethinking aristocratic dilettantes who were a fixture of his age, Goethe–-writes poet Philip Brantingham—“was a universal genius, one of those talents whose works transcend race, nation, language-and even time.” It’s a dated concept, for sure, but when we think of genius in the old Romantic sense, we most often think of Goethe, as a poet, philosopher, and scientist. When he turned his attention to optics and the science of color, Goethe refuted the theories of Newton and created some enduring scientific art, which would later inspire philosophical iconoclasts like Wittgenstein and expressionist painters like Wassily Kandinsky.

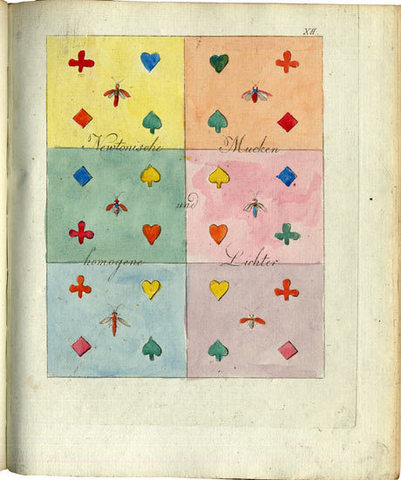

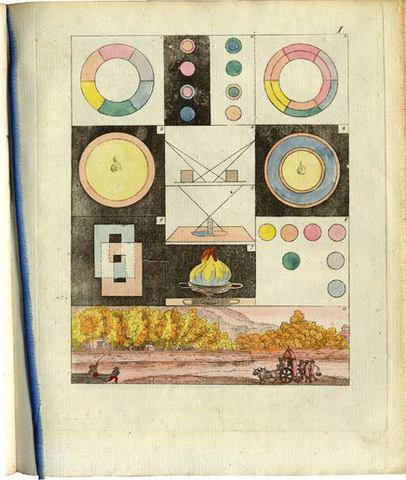

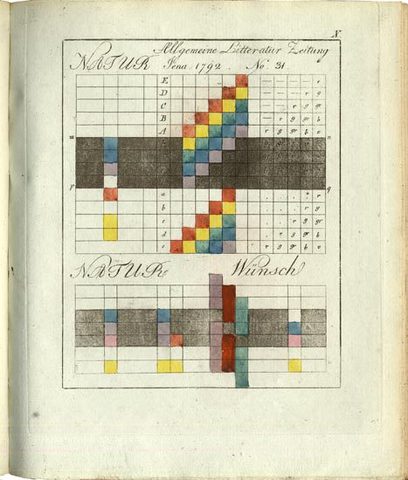

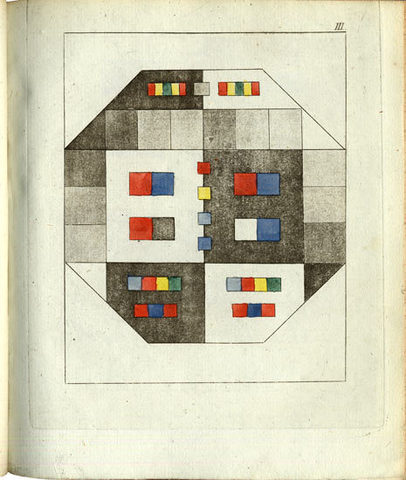

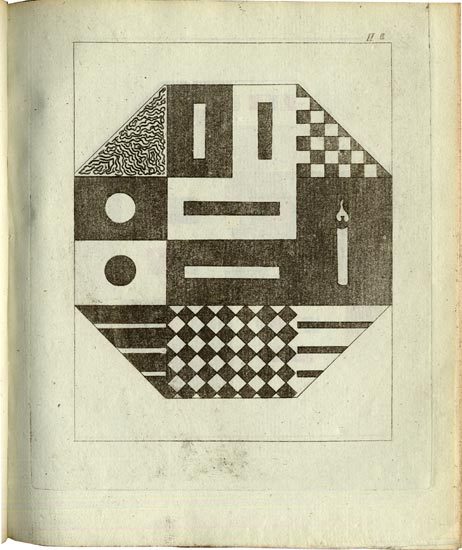

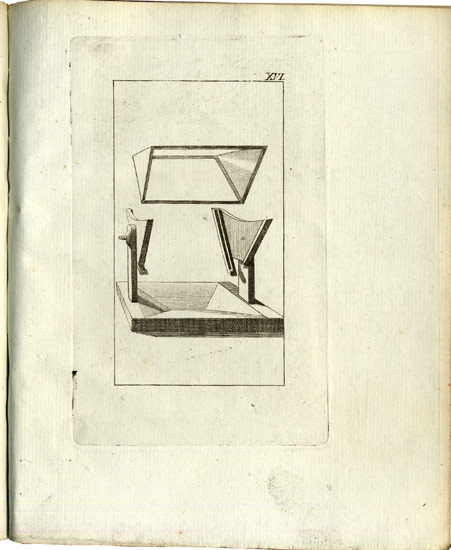

We’ve featured Goethe’s most important scientific work, Zur Farbenlehre (Theory of Colors), in a previous post. Now we can bring you the superior images above, from a first edition scan at Stockholm’s Hagerstromer Medical Library, who host a collection of scanned illustrations from dozens of first editions of naturalist texts. The collection spans a once suppressed physiology text by Descartes—another optics theorist—to Rachel Carson’s 1962 Silent Spring, the book that “launched the modern conservationist movement.” In-between, find scans of illustrations and photographs from the works of Carl Linnaeus, Charles Darwin, Louis Pasteur, and dozens of other natural philosophers and scientists who made significant contributions to medical science.

In the case of Goethe’s Theory of Colors (1810), we get a high-quality look at the images in what the author himself considered his best work. “Known as a fierce attack on Newton’s demonstration that white light is composite,” writes the Hagerstromer Library, “Goethe’s colour theory remains an epochmaking work.” Goethe’s illustrations came directly from “a large number of observations of subjective colour-perceptions, recorded with all the exactness of a scientist and the keen insight of an artist.” It’s partly the bridging of sciences and the arts—of Enlightenment and Romanticism—that has made Goethe such a remarkable figure in European intellectual history. But as many of the finely illustrated, carefully observed texts at the Hagerstromer Medical Library show, he wasn’t alone in that regard.

In addition to these classic texts, the Hagerstromer also hosts the Wunderkammer, an eclectic archive of (often quite bizarre) naturalist images and illustrations from the 16th to the 20th centuries. One MetaFilter user describes the collection thus:

Wunderkammer is a collection of high resolution images from old books in the Hagströmer Medical Library. Some of my favorites are sea anemones, nerve cells, rooster chasing off a monster, 16th Century eye surgery, muscles and bones of the hand and arm, elephant-headed humanoid and cupping. It can also be browsed by tag, broken up into subject (e.g. beast), emotion (e.g. strange), technique (e.g. chromolithography) and era (e.g. 18th Century).

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

A rich, rich mind.