“There comes Poe with his raven,” wrote the poet James Russell Lowell in 1848, “like Barnaby Rudge, / Three-fifths of him genius and two-fifths sheer fudge.” Barnaby Rudge, as you may know, is a novel by Charles Dickens, published serially in 1841. Set during the anti-Catholic Gordon Riots of 1780, the book stands as Dickens’ first historical novel and a prelude of sorts to A Tale of Two Cities. But what, you may wonder, does it have to do with Poe and “his raven”?

Quite a lot, it turns out. Poe reviewed the first four chapters of Dickens’ Barnaby Rudge for Graham’s Magazine, predicting the end of the novel and finding out later he was correct when he reviewed it again upon completion. He was particularly taken with one character: a chatty raven named Grip who accompanies the simple-minded Barnaby. Poe described the bird as “intensely amusing,” points out Atlas Obscura, and also wrote that Grip’s “croaking might have been prophetically heard in the course of the drama.”

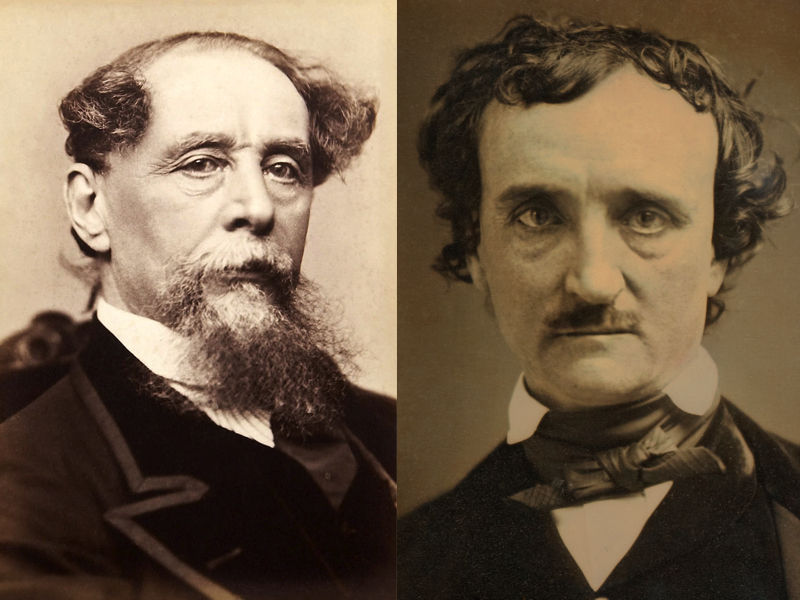

It chanced the following year the two literary greats would meet, when Poe learned of Dickens’ trip to the U.S.; he wrote to the novelist, and the two briefly exchanged letters (which you can read here). Along with Dickens on his six-month journey were his wife Catherine, his children, and Grip, his pet raven. When the two writers met in person, writes Lucinda Hawksley at the BBC, Poe “was enchanted to discover [Grip, the character] was based on Dickens’s own bird.”

Indeed Dickens’ raven, “who had an impressive vocabulary,” inspired what Dickens called the “very queer character” in Barnaby Rudge, not only with his loquaciousness, but also with his distinctively ornery personality. Dickens’ daughter Mamie described the raven as “mischievous and impudent” for its habit of biting the children and “dominating” the family’s mastiff, such that the bird was banished to the carriage house.

Image courtesy of the Free Library of Philadelphia.

But Dickens—who Jonathan Lethem calls the “greatest animal novelist of all time”—loved the bird, so much that he wrote movingly and humorously of Grip’s death, and had him stuffed. (A not unusual practice for Dickens; we’ve previously featured a letter opener Dickens had made from the paw of his cat, Bob.) The remains of the historical Grip now reside in the rare book section of the Free Library of Philadelphia, “a stuffed raven” writes The Washington Post’s Raymond Lane, “about the size of a big cat.” (See Grip above.)

Of the literary Grip’s influence on Poe, Janine Pollack, head of the library’s rare books department, tells Philadelphia magazine, “It is sort of a unique moment in literature when these two great writers are sort of thinking about the same thing. You think about how much the two men were looking at each other’s work. It’s almost a collaboration without them realizing it.” But can we be sure that Dickens’ Grip, real and imagined, directly inspired Poe’s “The Raven”? “Poe knew about it,” says historian Edward Pettit, “He wrote about it. And there’s a talking raven in it. So the link seems fairly obvious to me.”

Lane adduces some clear evidence of passages in the the novel that sound very much like Poe: “At the end of the fifth chapter,” for example, “Grip makes a noise and someone asks, ‘What was that—him tapping at the door?’ Another character responds, ‘’Tis someone knocking softly at the shutter.’” Hawksley notes even more similarities. “Although there is no concrete proof,” she writes, “most Poe scholars are in agreement that the poet’s fascination with Grip was the inspiration for his 1845 poem The Raven.”

Where we often find surprising lineages of influence from author to author, it’s unusual that the connections are so direct, so personal, and so odd, as those between Poe, Dickens, and Grip the talking raven. I’m especially struck by an irony in this story: Poe courted Dickens in 1842 “to impress the novelist,” writes Sidney Moss of Southern Illinois University, “with his worth and versatility as a critic, poet, and writer of tales,” and with the aim of establishing a literary reputation, and publishing contracts, in England.

While Dickens seemed duly impressed, and willing to help, nothing commercial came of their exchange. Instead, Dickens and his raven inspired Poe to write the most famous poem of his life, “The Raven,” for which he will be remembered forevermore.

Related Content:

Charles Dickens Gave His Cat “Bob” a Second Life as a Letter Opener

The Historic Meeting Between Dickens and Dostoevsky Revealed as a Great Literary Hoax

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Interesting tale, we have a Dickens opera house here where I live and it is said it is a relative of the famous Dickens. He had his dog stuffed when it escaped and got hit by a train I believe, The Dickens here was murdered…

Poe himself give a precise account of how he composed The Raven which you can read here: http://www.eapoe.org/works/essays/philcomp.htm

He doesn’t mention Grip. In fact, he had initially thought to make the bird a parrot!

Better check your facts. Grip died in 1841. Dickens came to American the first time in March of 1842.

Great story! Thx. You just never know what 2 people meeting will produce. I often can’t figure out the purpose of most of my life or relationships till retrospect.

Great story! Thx. You just never know what 2 people meeting will produce. I often can’t figure out the purpose of most of my life or relationships till retrospect. They say I already said this but I have not been here till 3 hrs ago. Are you glitching? Is it hello from #AI or us my identity just stolen. I accepted a bunch of new friends around that hour, so I am guessing one got into my account? Hi #FBI! I believe u might be here?👀