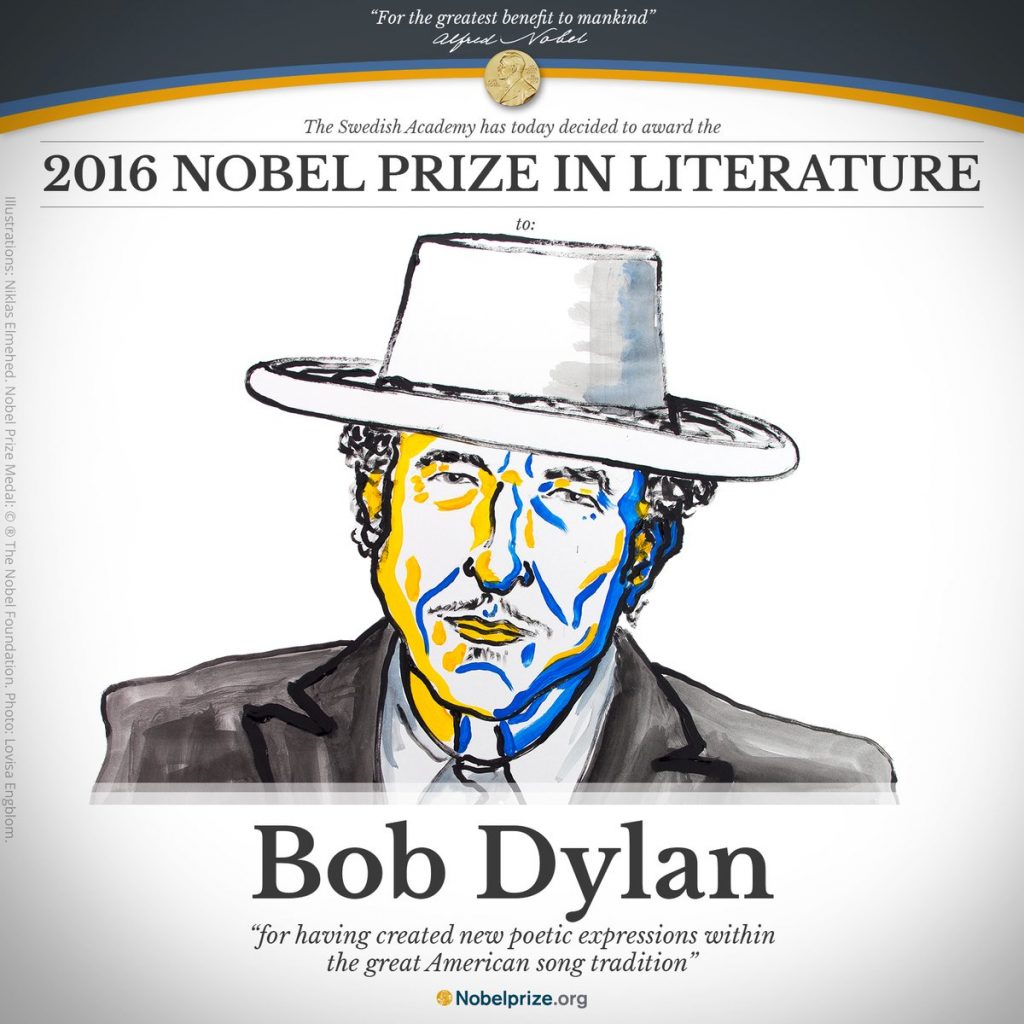

Image courtesy of The Nobel Prize’s Twitter stream.

His apocalyptic poetry plucks images and forms from the blues, the Bible, the Beats, Symbolists, William Blake, T.S. Eliot, and a balladeer tradition dating from medieval French and English minstrelsy to Appalachian settlement to Woody Guthrie, his first muse. His narrative voice shifts from work to work as he has fully embodied various American characters for over half a century—folk troubadour, rock and roll trickster, earnest country crooner, evangelist, weary bluesman, starry-eyed jazz singer. “There is no systematic way of analyzing Dylan’s song lyrics or poems,” writes Julia Callaway at the Oxford Dictionaries blog; “they span more than five decades of historical context and musical style. But perhaps one of the most interesting sides of Dylan is how he uses language and his lyrics to project certain identities, including folksinger and protest-musician.”

Dylan began in that tradition with songs like “The Times They Are A‑Changin’” and “A Hard Rains A‑Gonna Fall”—picking up Guthrie’s inflections and mannerisms in ballads much more sophisticated than they seemed at first listen. “A Hard Rain’s A‑Gonna Fall” is a “seven minute epic,” writes Rolling Stone, “that warns against a coming apocalypse while cataloging horrific visions—gun-toting children, a tree dripping blood—with the wide-eyed fervor of John the Revelator.” The song “began life as a poem, which Dylan likely banged out on a typewriter owned by his buddy… Wavy Gravy.” Dylan has been ambivalent about whether or not we should call him a poet, but this is how so much of his work took shape—banged out on typewriters in New York apartments—as poetry set to music. “Every line in [A Hard Rain’s A‑Gonna Fall] is actually the start of a whole song,” said Dylan, “but when I wrote it, I thought I wouldn’t have enough time alive to write all those songs, so I put all I could into this one.”

After over five decades of lyrics packed with allusion and densely woven themes and meanings, Dylan has had time to write those songs—several more apocalyptic epics set to a few chords on the acoustic guitar. “There are some novels, some trilogies, in fact, with less actual content than Bob Dylan’s ‘All Along the Watchtower,’” says the Nerdwriter in the analysis of that cryptic John Wesley Harding song above. One could say the same about certain songs that appear on nearly every Dylan record, like the 11-minute “Desolation Row,” below. Amid only a few missteps, Dylan has released album after album, decade after decade, that showcase his unparalleled wordcraft in various song forms. And some of his finest work has appeared only in recent years, when it seems his career might have come to a close. Despite some mixed reactions—and some concern for Philip Roth—most people have responded to news this morning of his win for the Nobel Prize in Literature with a decided, “yes, of course.”

Dylan’s recognition by the Nobel Committee validates not only the songwriter himself, but the form he embraced and shaped. As permanent secretary of the Swedish Academy Sara Danius remarked in her announcement, Dylan “created new poetic expressions within the American song tradition.” The award represents “a recognition of the whole tradition that Bob Dylan represents,” says critic David Hadju, “so it’s partly a retroactive award for Robert Johnson and Hank Williams and Smokey Robinson and the Beatles. It should have been taken seriously as an art form a long time ago.” One could argue that American song has already been taken as seriously as any art form, but that it isn’t literature.

Several people have done so. As New York Times writer Hiroko Tabuchi put it, “this might be a disappointing day for booksellers and publishers.” Hardly. Not only does Dylan have a memoir out, Chronicles: Volume One, the first of a planned trilogy, but we may also find renewed appreciation for his first book, 1966’s Tarantula. Dylan’s songs and drawings have been turned into picture books, published in collections, and pored over in biography after biography, commentary after commentary. And next month, Dylan himself will release The Lyrics: Since 1962, a comprehensive, definitive collection of the songwriter’s lyrics, complete with expert annotations. You can pre-order a copy here.

The literary output by and about Dylan should keep booksellers busy for many months after this announcement. But Dylan’s is primarily a living, bardic tradition, lest we forget that all literature began as song. So congratulations to Dylan and for perhaps long-overdue recognition of American songcraft as a genuinely literary art form.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Good for him! Too bad Carl Sandburg, Woody Guthrie, and Pete Seeger didn’t get Nobel’s for doing the same thing.

The ultimate in dumbing down.

Sorry, not quite the “same“thing. Good as those writers were, they in no way had the breadth of material nor the cultural impact Bob Dylan had. Simply put, they did not do “the same thing”.

I’ll bring the D