We’ve reached the final stretch of the most infuriating, unsettling election I’ve ever experienced. And we find the U.S. so polarized that—as The Wall Street Journal chillingly demonstrates in their “Blue Feed Red Feed” feature—the left and right seem to live in two entirely different realities. Still, one would have to work very hard on either side, I think, to deny the role sexism has played. One candidate, a known and well-documented misogynist, leads millions of supporters calling for his opponent’s death, imprisonment, and humiliation. That opponent, of course, happens to be the first woman to run on a major party ticket in a general election.

Do many Americans still have a problem with accepting women as leaders? I personally don’t think there’s much of an argument there, and people who see the question as redundant marvel at how long archaic attitudes about women in power have persisted. At least these days we can openly have the—often highly inflamed—conversation about sexism in business, entertainment, and government. And we can support a cultural industry thriving on strong female characters in fiction, film, and television. Not so much in 1928, when the Chicago Public Library banned The Wizard of Oz, writes Kristina Rosenthal at the University of Tulsa Department of Special Collections, “arguing that the story was ungodly for ‘depicting women in strong leadership roles.’”

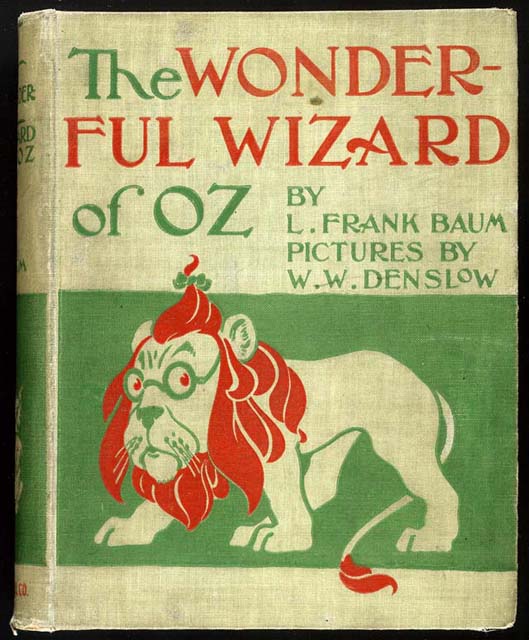

First published in 1900, L. Frank Baum’s fantasy novel initiated a series of 13 Oz-themed sequels, all of which became immensely popular after MGM’s 1939 film adaptation. (You can find them all in text and audio format here.) And yet, “throughout the years the books have been opposed for their positive portrayals of femininity.” Various libraries used similar excuses to ban the books throughout the 50s and 60s. The Detroit public library banned the Oz books in 1957, stating they had “no value for children of today.” The ban remained in place until 1972. One Florida librarian circulated a memo to her colleagues calling the books “unwholesome,” among other things, and causing a run on local bookstores as children desperately tried to find them.

Other groups decided that the books promoted witchcraft in charges similar to those levied at the Harry Potter series. In 1986, a group of Fundamentalist Christian families in Tennessee came together to remove the The Wizard of Oz from their schools’ curriculum, protesting “the novel’s depiction of benevolent witches.” They argued, writes Rosenthal, “that all witches are bad, therefore it is ‘theologically impossible ‘for good witches to exist.” Many seeking to ban the books since have similarly referred to their positive depictions of magic and “godless supernaturalism,” but the Tennessee case stands as a landmark in the Religious Right’s litigious crusade against the government. The attorney who represented plaintiff Vicki Frost called on “every born-again Christian to get their children out of public schools.”

It’s odd to think of whimsical children’s literature so seemingly innocuous as The Wizard of Oz books as territory in the long culture wars of the 20th century. But as we are reminded every year during Banned Books Week (September 25 − October 1, 2016), literature often arouses the ire of those incensed by change and difference. Yet their attempts to suppress certain books have always backfired, making the targets of their censorship even more popular and sought-after. If you’d like to read Baum’s Oz books now, you needn’t confront a gatekeeping librarian; simply head over to our post on the complete Wizard of Oz series, with free eBooks and audio books of all 14 female-centric fantasy classics.

Related Content:

800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices

The Complete Wizard of Oz Series, Available as Free eBooks and Free Audio Books

74 Free Banned Books (for Banned Books Week)

1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

I’ve always known it as L. Frank Baum, not Frank L., and a very quick search I could find no other instances where that was used. I could be wrong and am curious to be corrected. Nit picky, I know, as I think this is an otherwise well-written, thought provoking article.

Thanks, corrected!

There’s an error in the Rosenthal article you cite here. The 1928 ban on the book for “depicting women in strong leadership roles” applied to public libraries in Chicago, not all public libraries nationwide (although I wouldn’t be surprised if some other towns did ban it around the same time).