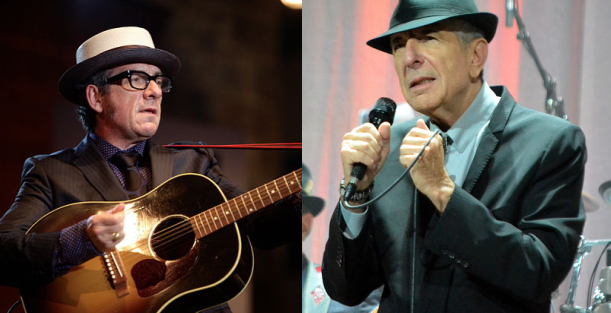

In every musician’s discography, one album has to rank at the bottom. In the case of the prolific and respected singer-songwriter Elvis Costello, fans and critics alike tend to single out 1984’s Goodbye Cruel World, which even Costello himself once described as “our worst album.” But with an artist like him doing the creating, even the duds hold a certain interest, or have a value at their core that emerges in unexpected ways. “Among the most discordant songs on the album was the forgettable ‘The Deportees Club.’ But then, years later, Costello went back and re-recorded it as ‘Deportee,’ and today it stands as one of his most sublime achievements.”

That comes from “Halleluah,” a recent episode of Revisionist History, the new podcast from Malcolm Gladwell that we first featured back in June. Here, perhaps the best-known curious journalistic mind of our time asks where genius comes from. Or, less abstractly, he asks about “the role that time and iteration play in the production of genius, and how some of the most memorable works of art had modest and undistinguished births.” His other example from the realm of music gives the episode its title. It first appeared, in the same year as did Costello’s “The Deportees Club,” on Leonard Cohen’s Various Positions, not making much of an impact until a cover by John Cale, and then more so one by Jeff Buckley, made it the “Hallelujah” we know today.

“That’s awful,” moans Gladwell, cutting off a clip of Costello’s original “The Deportees Club” — this from a self-described Elvis Costello superfan, who in 1984 bought Goodbye Cruel World the week it came out, just like he bought every other Elvis Costello album the week it came out. He regarded it as unlistenable then and still regards it as unlistenable today, applying that adjective at least twice in this podcast alone. He goes easier on Cohen’s original “Hallelujah,” poking fun at its dirge-like seriousness. Then, being Malcolm Gladwell, he goes on to frame the story of how both songs became great—the former a personal obsession of his own, the latter a phenomenon covered by “nearly everyone”—in terms of a theory: some artists are Picasso, and others are Cézanne.

Artists of the Picasso model execute their works seemingly at a stroke, often after long periods spent consciously or unconsciously assembling a coherent vision. Artists of the Cézanne model execute, execute, and execute again, refining their way from an imperfect first product to a much more perfect final one. Sometimes the first iteration a Cézanne puts out emerges at the wrong time, the initial fate of “The Deportees Club” and “Hallelujah.” Neither song, each by a musician in his own way unsuited to the climate of pop perfectionism that prevailed in the mid-1980s, found its form right away. Both would fit well into an institution I’ve long dreamed of called the Museum of First Drafts: enter and behold just how far a creation still needs to go even after its “creation”—even when created by a Costello, a Cohen or a Cézanne.

You can download Gladwell’s episode here.

Related Content:

Rufus Wainwright and 1,500 Singers Sing Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah”

Street Artist Plays Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” With Crystal Glasses

Malcolm Gladwell Has Launched a New Podcast, Revisionist History: Hear the First Episode

Malcolm Gladwell: Taxes Were High and Life Was Just Fine

Malcolm Gladwell: What We Can Learn from Spaghetti Sauce

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

I’m a long time fan of Elvis Costello. With much anticipation, I saw Elvis Costello perform just last Saturday, August 27, 2016 at the Ohana Festival in Dana Point, CA. Sadly, iterative or not, even genius can get “phoned-in” on occasion. In this case, he picked up a bull horn at one point of the performance and literally “mega-phoned-in” a part of a song. I think it was “The Other Side of Summer”. Whatever art was being worked on lost the crowd. Luckily it was a pretty afternoon in a beautiful place, Maybe next time.

I saw the same show in CA a few months ago and was blown away. The megaphone bit was sublime. I guess you caught him on an off night.

As for Hallelujah, I first heard it via the Cale cover in the movie Basquiat and then looked up the original. I preferred the Cale version back then, but over the years, Cohen’s understated, soulful performance of it has won me over. Could be, as you write, I wasn’t ready for it back then. Never did like the Buckley version that much, although of course he had a heavenly voice.

Gladwell’s “Hallelujah“t beautifully and movingly describes the music, then moves to powerful insights on creativity, hard work, and the nature of how each of us can better understand our contributions.

The story of the music is well told, but to focus only on the songs is to miss the shift to the different paths of genius. This discussion inspires me as faculty in both teaching and my own writing.

When I compare this podcast with Gladwell’s “Carlos Does Not Remember”, another valuable set of insights emerge on teaching, education, genius and development of the contributions in each of us.

I am grateful for how Gladwell crafts the research and story telling to offer these thoughtful insights. I look forward to future “Revisionist History”