Hundreds of years before vast public/private partnerships like Google Arts & Culture, the Vatican served as one of the foremost conservators of cultural artifacts from around the world. In the era of the Holy Roman Empire, few of those works were available to the masses (excepting, of course, the city’s considerable public architecture and sculpture). But with over 500 years of history, Vatican Museums and Libraries have amassed a trove of artifacts that rival the greatest world collections in their breadth and scope, and these have slowly become public over time. In 1839, for example, Pope Gregory XVI founded the Egyptian Museum, an extensive collection of Egyptian and Mesopotamian artifacts including the famous Book of the Dead. We also have The Collection of Modern Religious Art, which holds 19th and 20th century impressionists, surrealists, cubists, expressionists, etc. In-between are large public collections from antiquity to the Renaissance.

When it comes to manuscripts, the Vatican Library is no less an embarrassment of riches. But unlike the art collections, most of these have been completely inaccessible to the public due to their rarity and fragility. That’s all going to change, now that ancient and modern conservation has come together in partnerships like the one the Library now has with Japanese company NTT DATA.

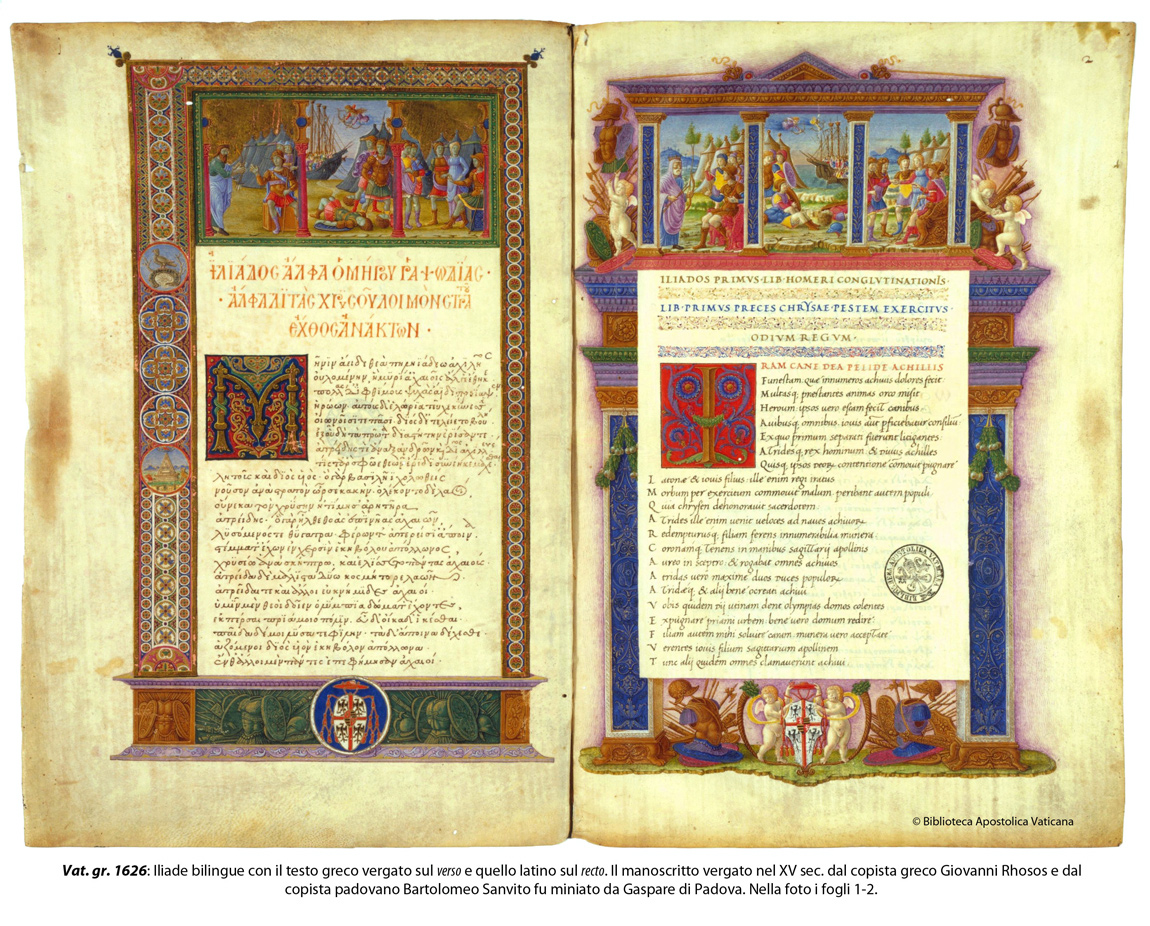

Their combined project, the Digital Vatican Library, promises to digitize 15,000 manuscripts within the next four years and the full collection of over 80,000 manuscripts in the next decade or so, consisting of codices mostly from the “Middle Age and Humanistic Period.” They’ve made some excellent progress. Currently, you can view high-resolution scans of over 5,300 manuscripts, from all over the world. We previously brought you news of the Library’s digitization of Virgil’s Aeneid. They’ve also shared a finely illustrated, bilingual (Greek and Latin) edition of its predecessor, The Iliad (top).

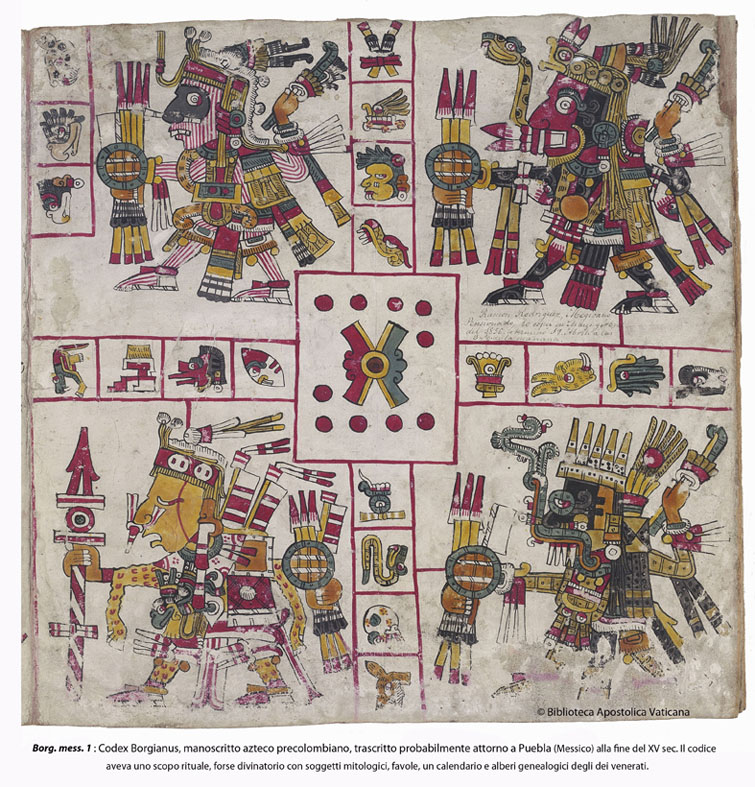

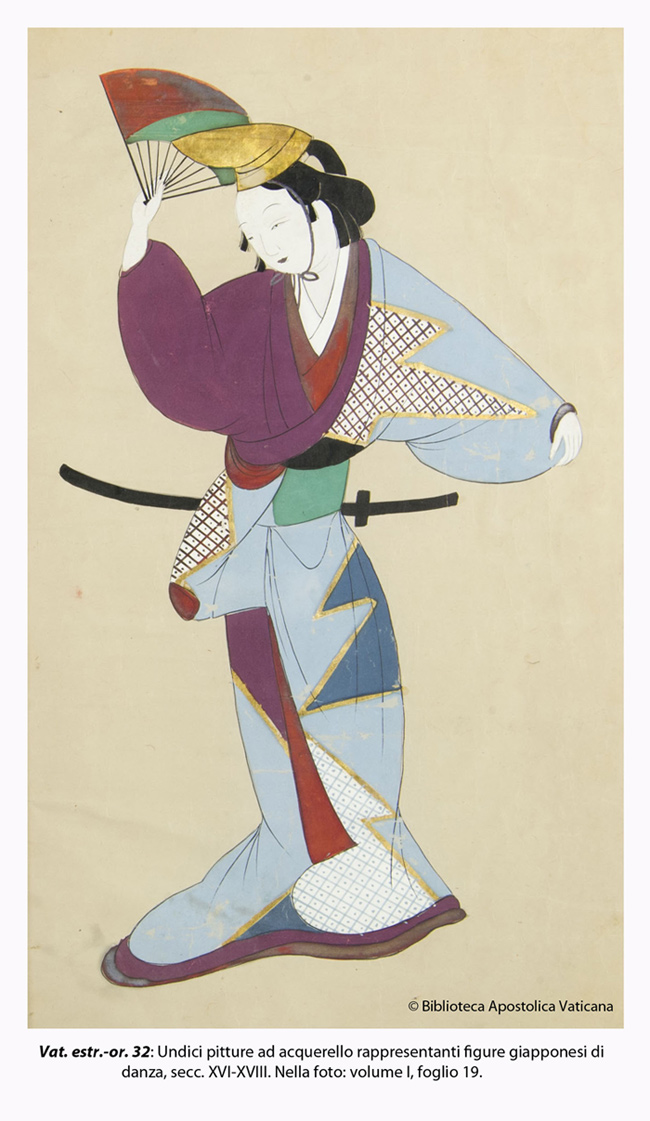

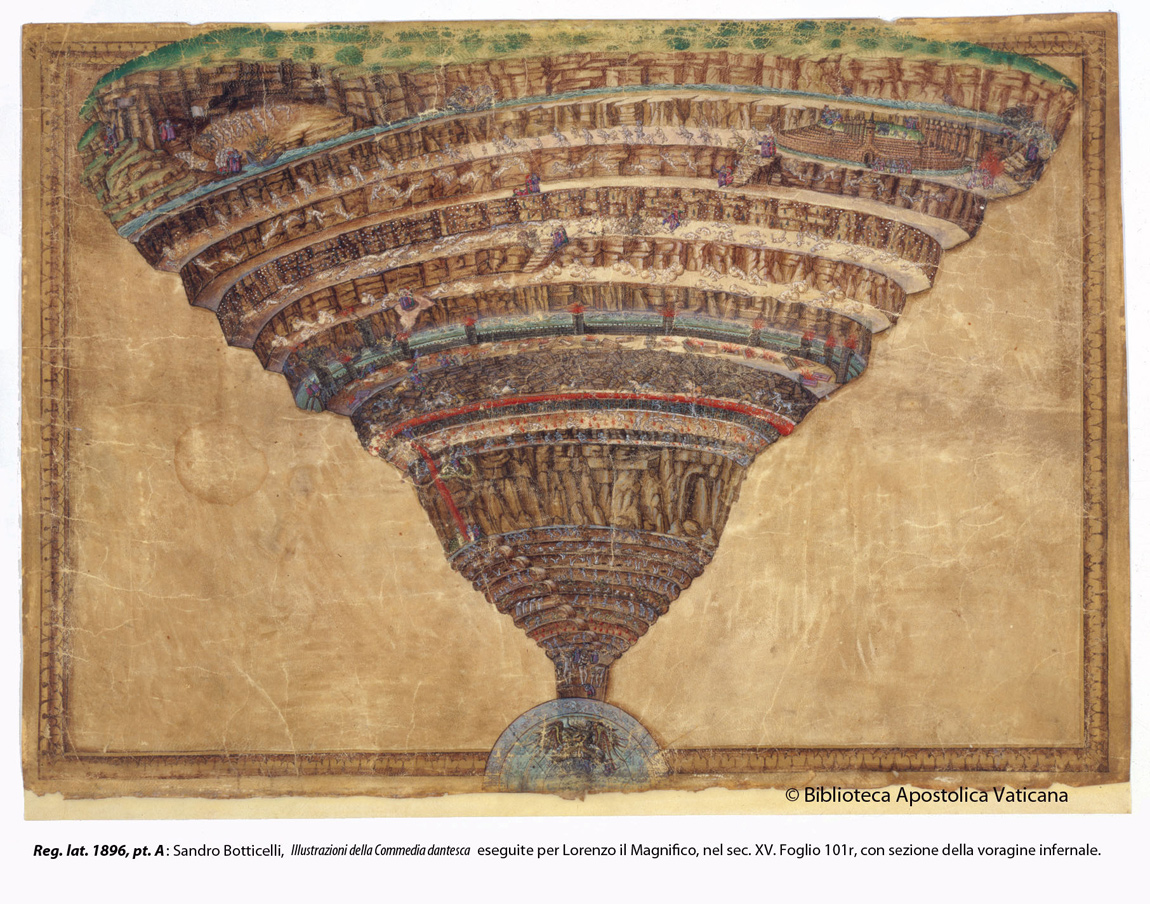

Further up, from a similar time but very different place, we see a Pre-Columbian Aztec manuscript, equally finely-wrought in its hand-rendered intricacies. You’ll also find illustrations like the circa 17th-century Japanese watercolor painting above, and the rendering of Dante’s hell, below, from a wonderful, if incomplete, series by Renaissance great Sandro Botticelli (which you can see more of here). Begun in 2010, the huge-scale digitization project has decided on some fairly rigorous criteria for establishing priority, including “importance and preciousness,” “danger of loss,” and “scholar’s requests.” The design of the site itself clearly has scholars in mind, and requires some deftness to navigate. But with simple and advanced search functions and galleries of Selected and Latest Digitized Manuscripts on its homepage, the Digital Vatican Library has several entry points through which you can discover many a textual treasure. As the site remarks, “the world’s culture, thanks to the web, can truly become a common heritage, freely accessible to all.” You can enter the collection here.

Related Content:

1,600-Year-Old Illuminated Manuscript of the Aeneid Digitized & Put Online by The Vatican

Botticelli’s 92 Illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy

15,000 Colorful Images of Persian Manuscripts Now Online, Courtesy of the British Library

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply