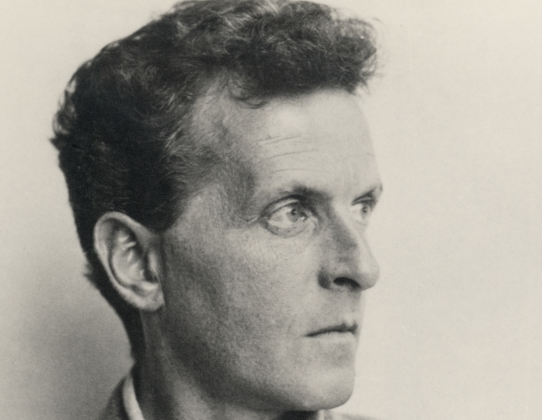

Image by Austrian National Library, via Wikimedia Commons

What is it about Austrian philosophical prodigy Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus that so inspires artists? Jasper Johns, the Coen Brothers, Derek Jarman…. Perhaps it’s easy to see his appeal to writers. His succinct philosophy of language contains a groundbreaking claim, for its time, wrote Bertrand Russell in his 1922 introduction: “In order that a certain sentence should assert a certain fact there must… be something in common between the structure of the sentence and the structure of the fact.”

There may be no higher praise for careful, precise language. Recalling the stock advice to “show, don’t tell,” Wittgenstein asserted that whatever bonds together the structure of sentences and the structure of the world, it is only something we can show, not something we can say. In this regard, Wittgenstein also elevated images, and he himself had a keen eye for photography and architecture. Of course, the imaginative, mystical aspect of Wittgenstein’s little book of aphorisms and symbols appeals to musicians and composers as well.

John Cage drew heavily on Wittgenstein’s work and the Tractatus has been adapted by others in musical pieces ranging from the understated and meditative to the comically ridiculous. The adaptation above takes a stark operatic approach. Composed by Balduin Sulzer, the “one woman opera,” as the singer Anna Maria Pammer’s site describes it (in Google translation from German), “drives the meticulousness and insistence of the text on the top.” Drawing on the work of the Second Viennese School, “the basic musical idea comes from the music of the time of origin of the Tractatus, i.e. the time of World War I.”

Wittgenstein has long been associated with Arnold Schoenberg and the Tractatus has been called a “tone poem.” The chilliness, alternating with rapid crescendos, with which Pammer delivers the philosophical libretto recalls the book’s tenor, as well as Wittgenstein’s temperament more generally. Given to violent outbursts and fits of derision, Wittgenstein spent the first part of his life attempting to create perfect systems— “a logically perfect language,” wrote Russell. In between this austere pursuit, he lived just as austerely and sometimes violently. John Cage’s enactment of Wittgenstein’s theories comes closer to the intent of “show don’t tell,” but Sulzer’s adaptation perhaps best dramatizes the mystical ellipses of Wittgenstein’s first major work. If you need Spotify’s free software, download it here.

Related Content:

Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Gets Adapted Into an Avant-Garde Comic Opera

In Search of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Secluded Hut in Norway: A Short Travel Film

The Photography of Ludwig Wittgenstein

Free Online Philosophy Courses

Download 135 Free Philosophy eBooks: From Aristotle to Nietzsche & Wittgenstein

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Elizabeth Lutyens set it as well. Great woman, awful composer, horrible piece.

It’s, of course, a heroic attempt to sing a difficult and terse text. In times of mixing media many things go that you would believe cannot. Convinced I am not at all. Only those who know the Tractatus well will take anything out of this.

Of course, Wittgenstein was Austrian, not German, as wrongly stated in the article.