For almost two hundred years, English gentlemen could not consider their education complete until they had taken the “Grand Tour” of Europe, usually culminating in Naples, “ragamuffin capital of the Italian south,” writes Ian Thomson at The Spectator. Italy was usually the primary focus, such that Samuel Johnson remarked in 1776, perhaps with some irony, “a man who has not been to Italy is always conscious of an inferiority.” The Romantic poets famously wrote of their European sojourns: Shelley, Byron, Wordsworth… each has his own “Grand Tour” story.

Shelley, who traveled with his wife Mary Godwin and her stepsister Claire Clairmont, did not go to Italy, however. And Byron sailed the Mediterranean on his Grand Tour, forced away from most of Europe by the Napoleonic wars. But in 1817, he journeyed to Rome, where he wrote the Fourth Canto of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage:

Oh Rome! my country! city of the soul!

The orphans of the heart must turn to thee,

Lone mother of dead empires! And control

In their shut breasts their petty misery.

For the traveling artist and philosopher, “Italy,” Thomson writes, “presented a civilization in ruins,” and we can see in all Romantic writing the tremendous influence visions of Rome and Pompeii had on gentlemen poets like Byron. The Grand Tour, and journeys like it, persisted until the 1840s, when railroads “spelled the end of solitary aristocratic travel.” But even decades afterward, we can see Rome (and Venice) the way Byron might have seen it—and almost, even, in full color. As we step into the vistas of these postcards from 1890, we are far closer to Byron than we are to the Rome of our day, before Mussolini’s monuments, notorious snarls of Roman traffic, and throngs of tourists.

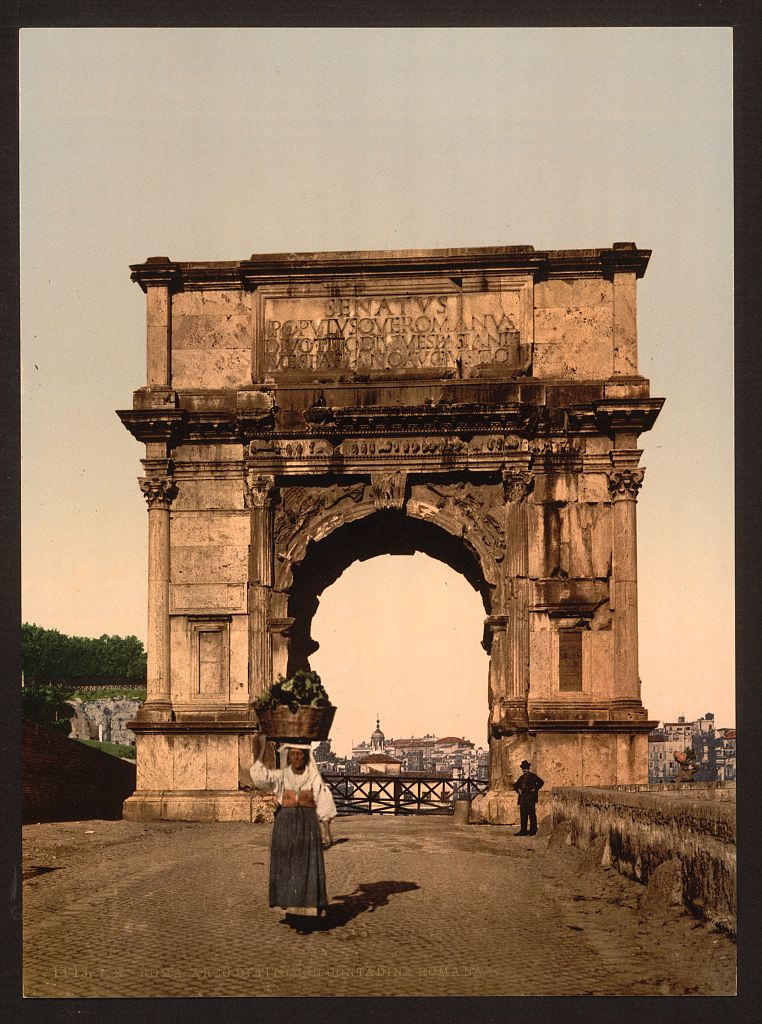

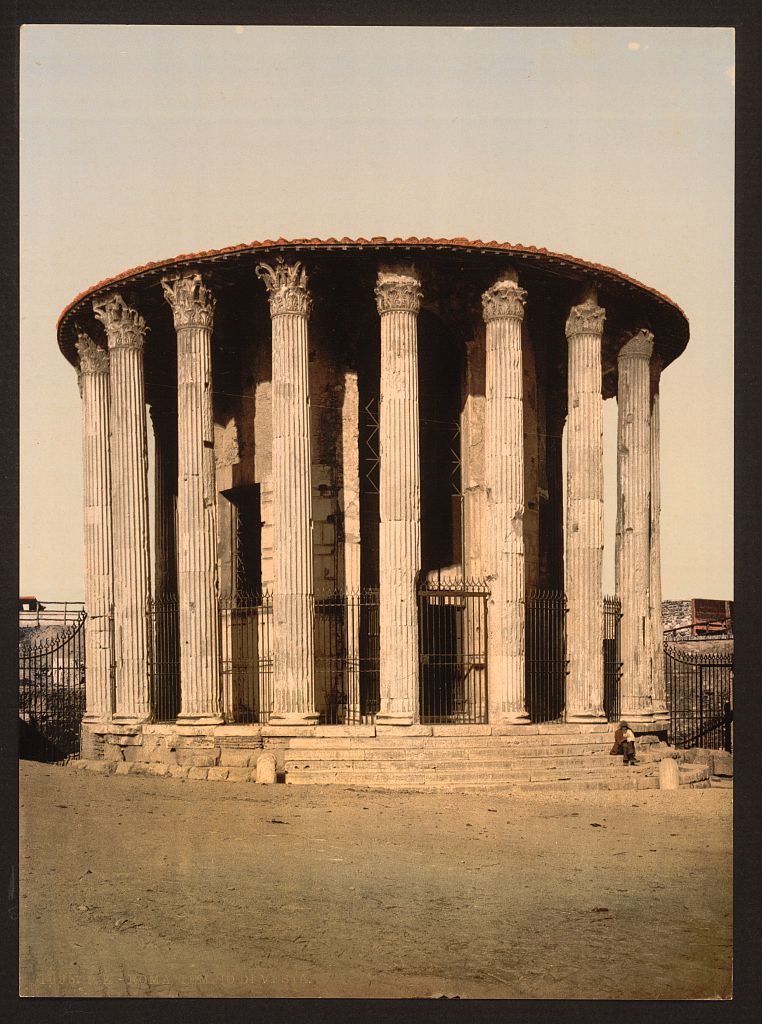

“These postcards of the ancient landmarks of Rome,” writes Mashable, “were produced… using the Photochrom process, which adds precise gradations of artificial color to black and white photos.” Invented by Swiss printer Orell Gessner Fussli, the process involved creating lithographic stone from the negatives—“Up to 15 different tinted stones could be involved in the production of a single picture, but the result was remarkably lifelike color at a time when true color photography was still in its infancy.”

The Library of Congress hosts forty two of these images in their online catalog, all downloadable as high quality jpegs or tiffs, and many, like the stunning image of the Colosseum at the top (see the interior here), featuring a pre-Photocrom black and white print as well.

Aside from a rare street scene, with an urban milieu looking very much from the 1890s, the photographs are void of crowds. In the foreground of the Triumphal Arch further up we see a solitary woman with a basket of produce on her head. In the image of San Lorenzo, above, a tiny figure walks away from the camera.

In most of these images—with their dreamlike coloration—we can imagine Rome the way it looked not only in 1890, but also how it might have looked to bored aristocrats in the 17th and 18th centuries—and to passionate Romantic poets in the early 19th, a place of raw natural grandeur and sublime man-made decay. See the Library of Congress online catalog to view and download all forty-two of these postcards. Also find a gallery at Mashable.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

“Shelley, who traveled with his wife Mary Godwin and her stepsister Claire Clairmont, did not go to Italy, however.”

Shelley drowned near Lerici, in the Gulf of La Spezia, in 1822. Er, that’s in Italy.