The story of the U.S.’s national parks isn’t one story, but many. These have been told and retold since the founding of the National Park Service, a century ago this past Thursday. And they stretch back even further, to the Civil War, the conquering and settling of the west, and the beginnings of the American conservation movement. Nearly every one of us who grew up within a cramped, contentious family car ride from one (or more) of those parks has our own story to tell. But our nostalgic memories can conflict with the history. Virginia and North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Parkway, for example—the park closest to my childhood home—offers visitors an idyllic vision of Appalachian life and landscape. But the founding and construction of the park in the 1930s and 40s was anything but.

On the one hand, the building of the gorgeously scenic, 469-mile highway provided jobs for out-of-work civilians and, later, conscientious objectors under FDR’s Works Progress Administration, Emergency Relief Administration, and Civilian Conservation Corps. On the other hand, the federal government’s seizure of the land created hardships for existing farmers and landowners, forced sometimes to sell their property or to obtain permission for building and development. The Park Service project also engendered resentment among the Eastern Cherokee, who fought the Parkway, and won some concessions. (In one story that represents both of these hardships, a Cherokee man Jerry Wolfe tells WRAL what it was like to work on the road, one that ran directly through the cabin he once shared with his parents.)

To celebrate their 100 years of existence, the National Park Service has launched what it calls its Open Parks Network, a portal to thousands of photographs and documents dating from the very beginnings of many of its parks—some of which, like Yosemite and Yellowstone, came under federal protection before the NPS existed, and some, like New York’s Stonewall Inn, only given protected monumental status this year. The Open Parks Network includes over 20 different parks and several dozen collections that document specific periods.

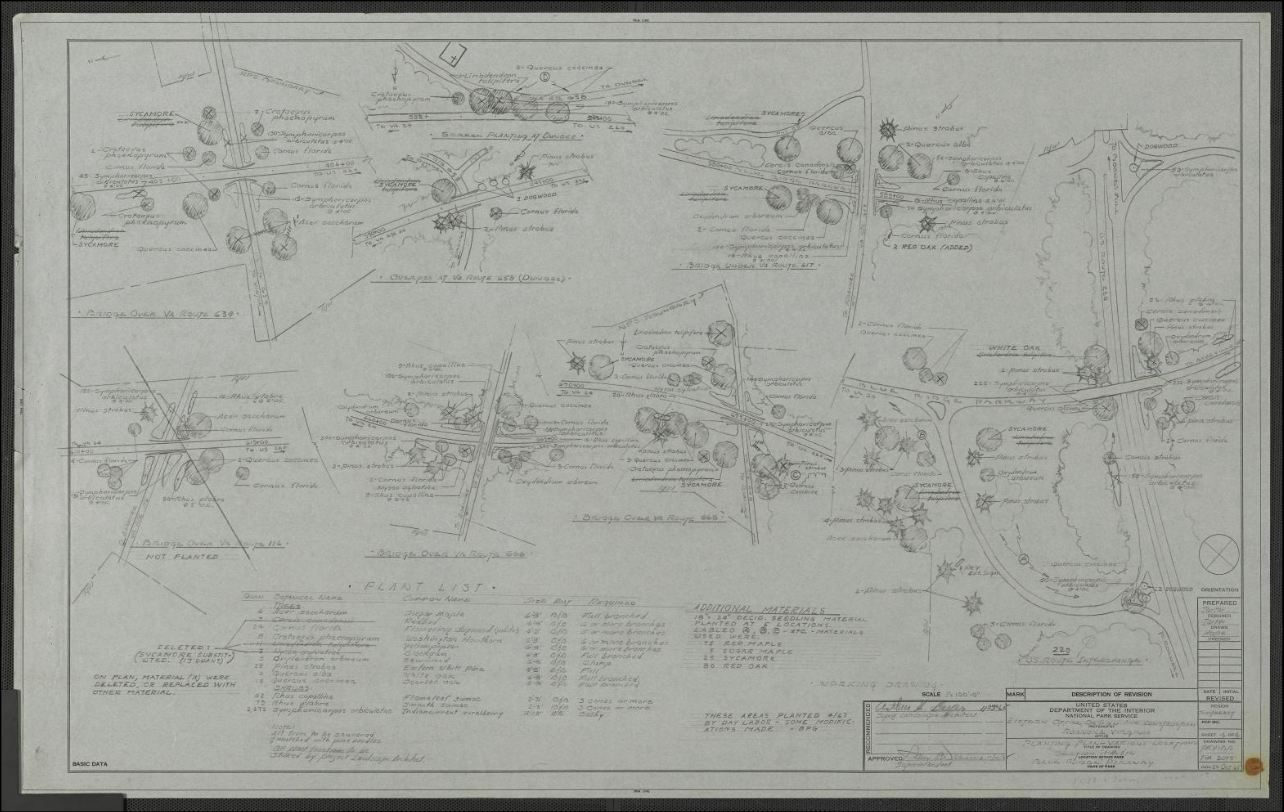

In the case of Blue Ridge Parkway, we have only one—a collection of the park’s engineering plans. One might hope for images of those toiling Depression-era crews, or of the anxious faces of the region’s residents. But instead we can piece together the story of the park through fascinating documents like the “Planting Plan” further up, from 1965, which reminds us how much the natural beauty of the Parkway is achieved through human intervention. And we can imagine what many of those early-20th century Appalachian folks looked like in historic photos like that above, from a collection of Great Smokey Mountains photographs taken in the teens and 20s by Jim Shelton.

Regardless of how much meddling we have done to create the scenic overlooks and mountain and Redwood underpasses that constitute the nation’s protected parks, there’s no denying their appeal to us all, nature lovers and otherwise, as symbols of the country’s rough grandeur. We can skip the hikes and long car rides, or plan for them in the future, surveying the parks’ beauty through over 100,000 high-resolution digital scans of photographs and 200,000 images in all, including more galleries of building plans, maps, and illustrations. Some of the galleries are quite unusual—like this collection of aerial infrared photographs of the Great Smoky Mountains, or this one of “historic goats” of the Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site. And many of the photos—like the faded 1968 photo of Yellowstone’s Old Faithful geyser, further up, look just like your family vacation photos.

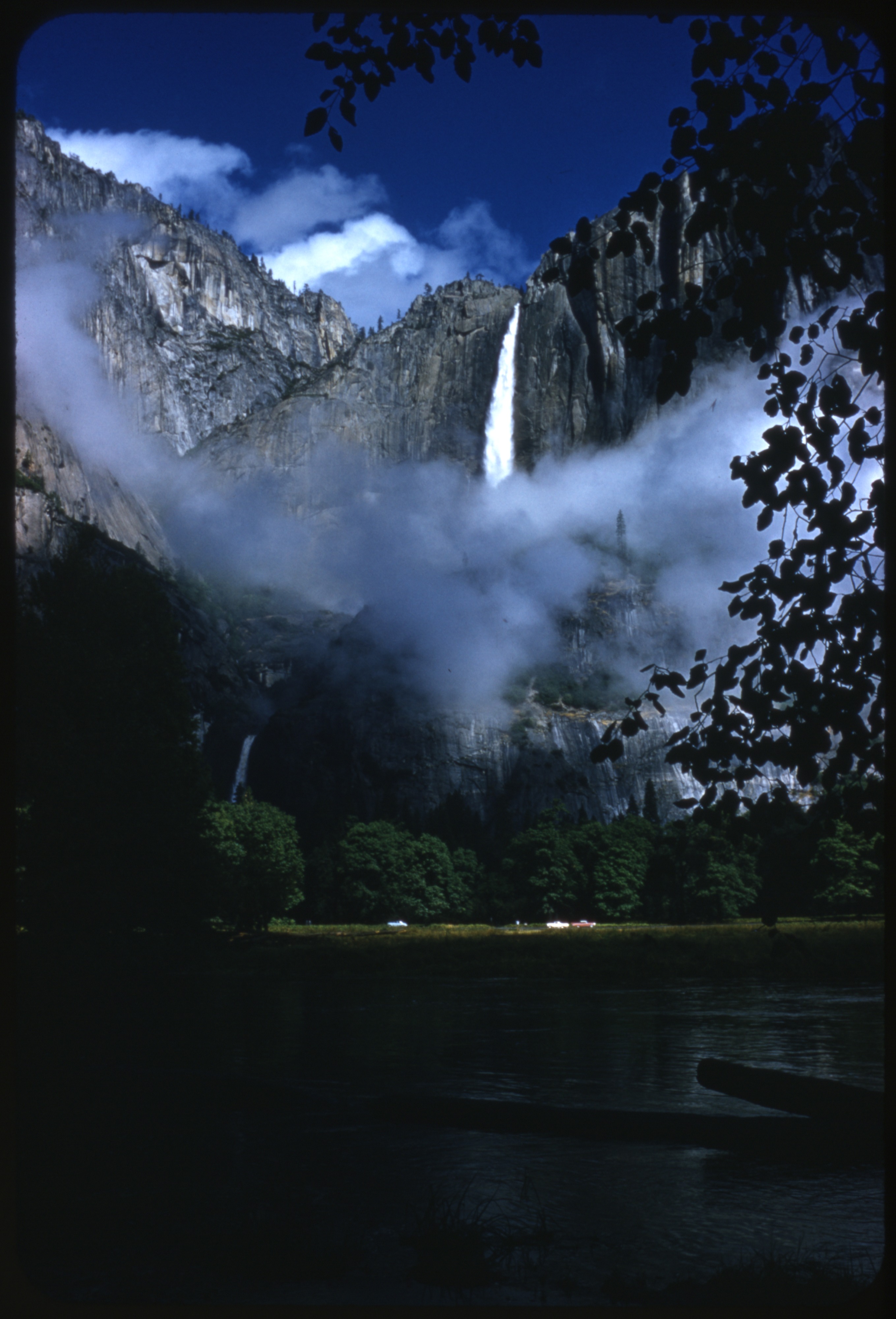

There are beautiful historical images like that of a house near Hodgenville, Kentucky, site of the Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historical Park, further up; images of park rangers and staff, like the charming group photo above from Andersonville National Historic Site in Georgia; and sublime vistas like the photo at the top of the post from the Kings Mountain National Military Park in Yosemite Valley. The Open Parks Network, writes Joe Toneli at Digg, “is constantly being added to, and is an important tool in preserving the history of the NPS and the national monuments it protects.” Developed in partnership with Clemson University since 2010, Open Parks hosts all public domain images, free to explore and download. See this guide for a detailed explanation on how to best navigate the collections, all of which are fully searchable.

Each image, like that of Yosemite Falls, above, has options for viewing full-screen and zooming in and out. So absorbing are these archives, you may find yourself getting lost in them, and any one of these beautifully-preserved parks and their incredible histories offer welcome places to get lost for several hours, or several days. For even more historic photography from the nation’s many parks, see selections online from the Eastman Museum’s current exhibit, Photography and America’s National Parks, “designed,” writes Johnny Simon at Quartz, “to inspire people to look at national landscape just as Teddy Roosevelt once did, a century ago.”

Enter Open Parks here.

Related Content:

226 Ansel Adams Photographs of Great American National Parks Are Now Online

The Beauty of Space Photography

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Great article about a truly wonderful resource. On the question of Blue Ridge Parkway images that depict work on 1930s crews, we have many such images from the Blue Ridge Parkway’s historic photograph collection on a site I co-direct at UNC-Chapel Hill: Driving Through Time: The Digital Blue Ridge Parkway. Driving Through Time includes nearly 8000 Parkway items (mostly historic photos, but also maps, drawings, oral histories, and newspaper articles). Together with Open Parks Network’s collection of Parkway maps and drawings, it help tell the complicated and fascinating story of the Parkway’s past. See: http://docsouth.unc.edu/blueridgeparkway/

Fantastic, thank you, Anne!