Surrealism, Discordianism, Frank Zappa, Situationism, punk rock, the Residents, Devo… the anarchists of counterculture in all their various guises may never have come into being—or into the being they did—were it not for an anti-art movement that called itself Dada. And like many of those anarchist countercultural movements and artists, Dada came about not as a playful experiment in “disrupting” the art world for fun and profit—to use the current jargon—but as a politically-charged response to rationalized violence and complacent banality. In this case, as a response to European culture’s descent into the mass-murder of World War One, and to the domestication of the avant-garde’s many proliferating isms.

The explicit tenets of Dada, in their intentionally scrambled way, were ecumenical, international, anti-elitist, and concerned with questions of craft. “The hospitality of the Swiss is something to be profoundly appreciated,” wrote poet Hugo Ball in his 1916 Dada manifesto, “And in questions of aesthetics the key is quality.” Ball conceived Dada as a means of reaching back toward primal origins, “to show how articulated language comes into being…. I shall be reading poems that are meant to dispense with conventional language, no less, and to have done with it.” Risking a lapse into solipsism, Ball sneered at “The word, the word, the word outside your domain, your stuffiness, this laughable impotence, your stupendous smugness, outside all the parrotry of your self-evident limitedness.” And yet, he concluded, “The word, gentlemen, is a public concern of the first importance.”

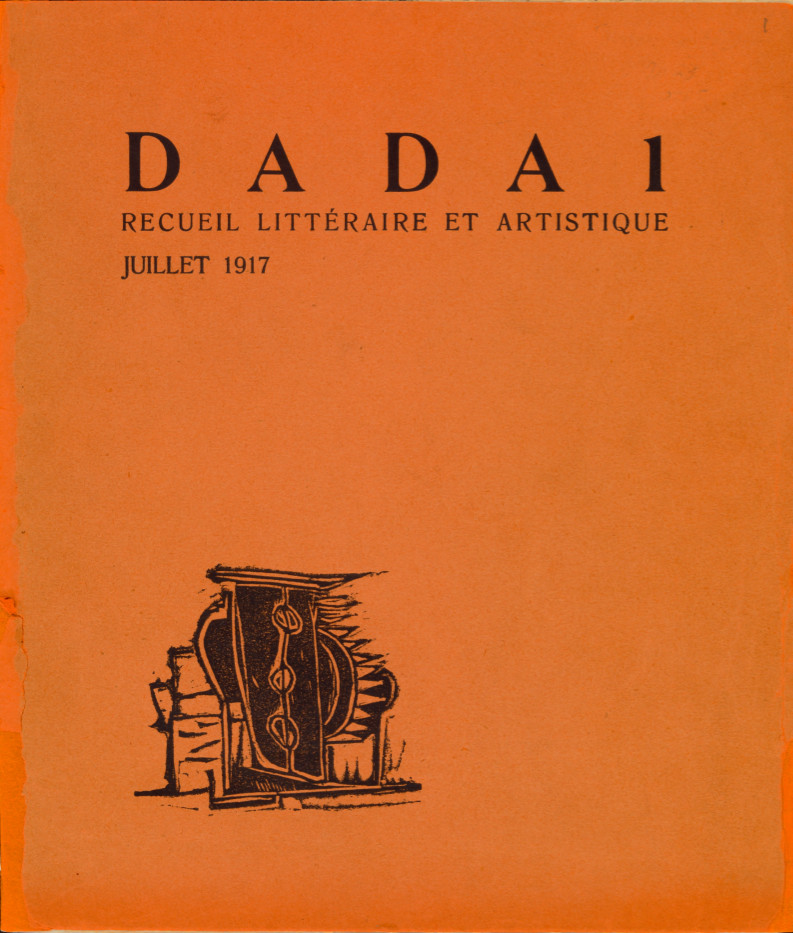

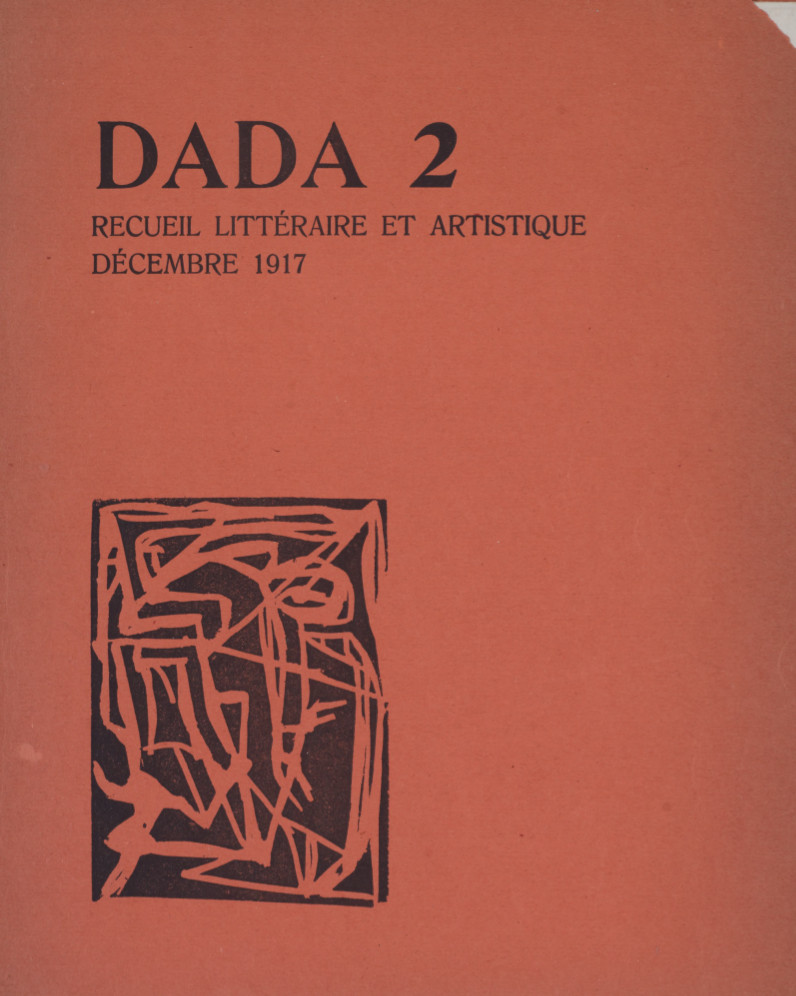

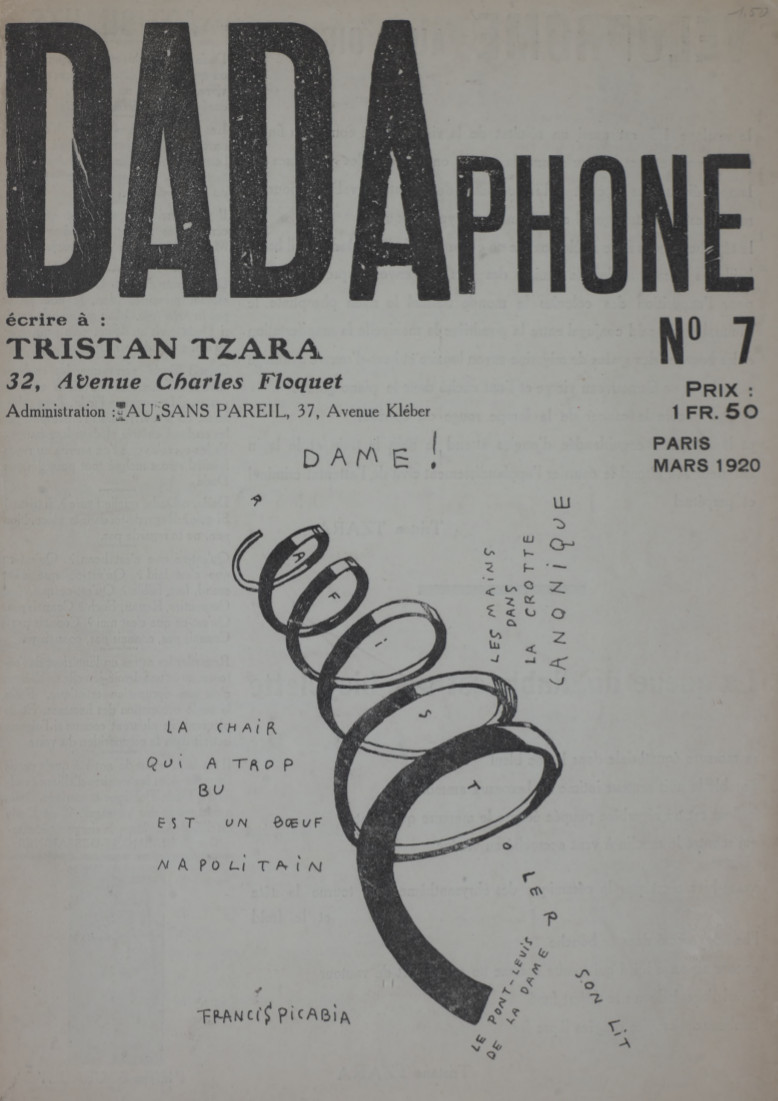

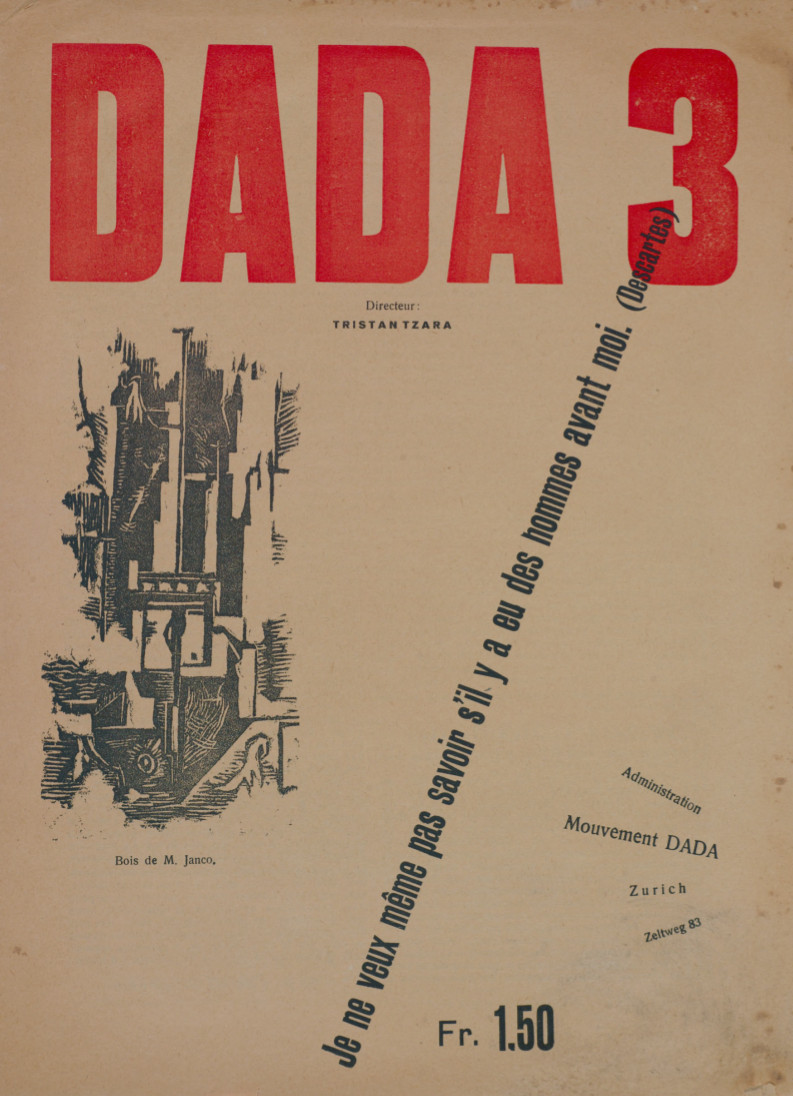

Two years later, artist Tristan Tzara issued a more bilious Dada manifesto with similar intent: “a need for independence… a distrust toward unity.” At once intensely political and anti-theoretical, he wrote, “Those who are with us preserve their freedom…. Here we are dropping our anchor in fertile ground.” How right he was, we can say 100 years later. “However short-lived,” writes Corinna da Fonseca-Wollheim in a New York Times celebration of Dada’s 100th anniversary, “Dada constitutes something like the Big Bang of Modernism.” Both Ball and Tzara positioned Dada as a collective, international movement. As such, it needed a publication to both centralize and spread its anti-establishment messages: thus Dada, the arts journal, first published in 1917 and printing 8 issues in Zurich and Paris until 1921.

Edited by Tzara and including his manifesto in issue 3, the magazine “served to distinguish and define Dada in the many cities it infiltrated,” writes the Art Institute of Chicago, “and allowed its major figures to assert their power and position.” Dada succeeded a previous attempt by Ball at a journal called Cabaret Voltaire—named for his Zurich theater—which survived for one issue in 1917 before folding, along with the first version of the cabaret. That year, Tzara, “an ambitious and skilled promoter… began a relentless campaign to spread the ideas of Dada…. As Dada gained momentum, Tzara took on the role of a prophet by bombarding French and Italian artists and writers with letters about Dada’s activities.” Whatever Dada was, it wasn’t shy about promoting itself.

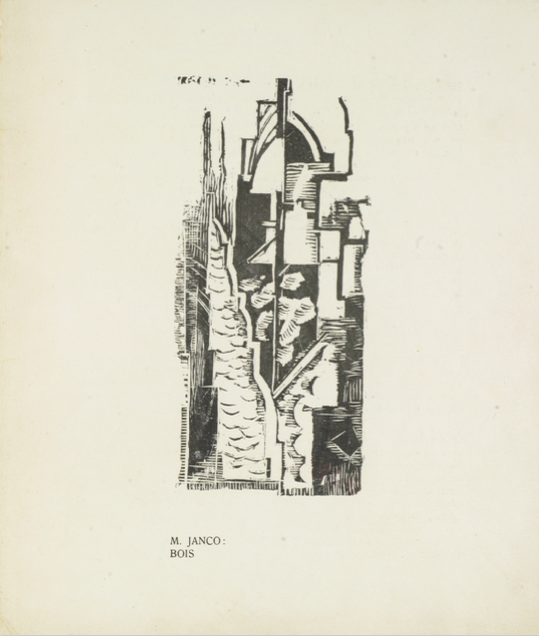

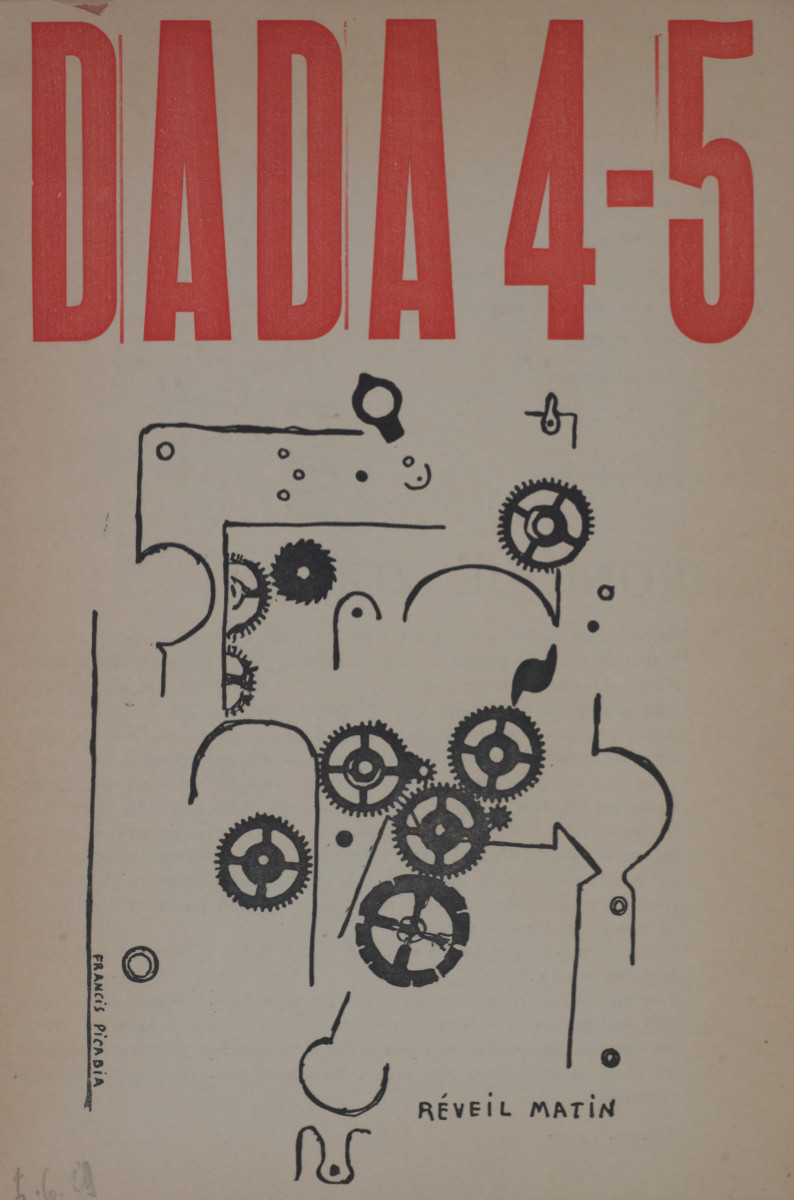

The first issue (cover at the top), contained commentary and poetry in French and Italian, and artwork like that above by important Romanian Dada artist, architect, and theorist Marcel Janco. Issues 4 and 5 were published together as an anthology, then World War I ended, and with travel again possible, Tzara, several Dada compatriots, and the journal moved to Paris. The final issue, Number 8, appeared in a truncated form. You can download each issue as a PDF from Monoskop or from Princeton University’s Blue Mountain Project, which also has an online viewer that allows you to preview each page before downloading.

Ball and Tzara were not the only assertive disseminators of Dada’s art and aims. The Art Institute of Chicago notes that in Berlin a “highly aggressive and politically involved Dada group” published its own short-lived journal, Der Dada, from 1919–1920. Download all three issues of that publication from the University of Iowa here.

Related Content:

Hear the Experimental Music of the Dada Movement: Avant-Garde Sounds from a Century Ago

Extensive Archive of Avant-Garde & Modernist Magazines (1890–1939) Now Available Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

am trying to download this fre stuff and am getting nowhere: either I get a download for a archive thingy I do not need or a thingy about calendars I do nt need — any idea?? thanks

I’m doing a second masters at the moment which encompasses the theme that the DADA mindset is likely the most relevant to address the horrors of contemporary violence.

Go to the paragraph ABOVE the Dada 4–5 cover and there are two links. I used the first one (Monoskop) and it will take you to a page allowing you to download each one.

Hope that helps!

Founded pre-1979 by Greg Service was “Send Out For Dada”. To be advertised on matchbook covers, one could call for Dada to be brought by ” our buisness(Dada sic)-like professional drivers” direct to your home. Some of my paintings I sold at The American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore were based on Greg’s ideas.

Greg Serafine ‚not ” SERVICE”. BUT NICE DADAISH MISTAKE.

hi walter — interesting hypothesis. how are you coming along with the research?

It is wonderful to have this book, so special. Thank you 🌳🌈🌬