You’ve likely heard a good deal recently—especially if you hang around these parts—about the 100th anniversary of Dada, supposedly begun when poet and Cabaret Voltaire owner Hugo Ball penned his manifesto in 1916 and began disseminating the ideas of the nascent anti-art movement. This makes a convenient origin story, as they say in the comics, and helps us contextualize the avant-garde explosion that followed. But, historically speaking, there is no such thing as creation ex nihilo, and the beginnings of Dada—before Ball coined the name—lie further back in time. (We might refer to the distinction Edward Said makes between a divine “origin” and a secular “beginning.”)

We could, as many do, situate the beginnings of Dada in the previous century, in Alfred Jarry’s bizarre 1896 play Ubu Roi or Erik Satie’s minimalist late 19th century Gymnopedies. We might also refer to an arts magazine in New York that preceded Tristan Tzara’s Dada and Ball’s single issue Cabaret Voltaire. Edited by famed photographer and art promoter Alfred Stieglitz, the journal 291 ran for 12 issues between 1915 and 1916 and is known, writes Dada-Companion.com, as “the first expression of the dada esthetic in the United States; proto-dada, actually, dada avant la lettre, before dada had started in Zürich in 1916.” Along with the University of Iowa, Ubuweb hosts the entire 12-issue print run, “a financial fiasco” in its day, “failing to sell more than eight subscriptions on vellum and a hundred on ordinary paper…. In the end Stieglitz sold the entire backstock to a ragpicker for $5.80.”

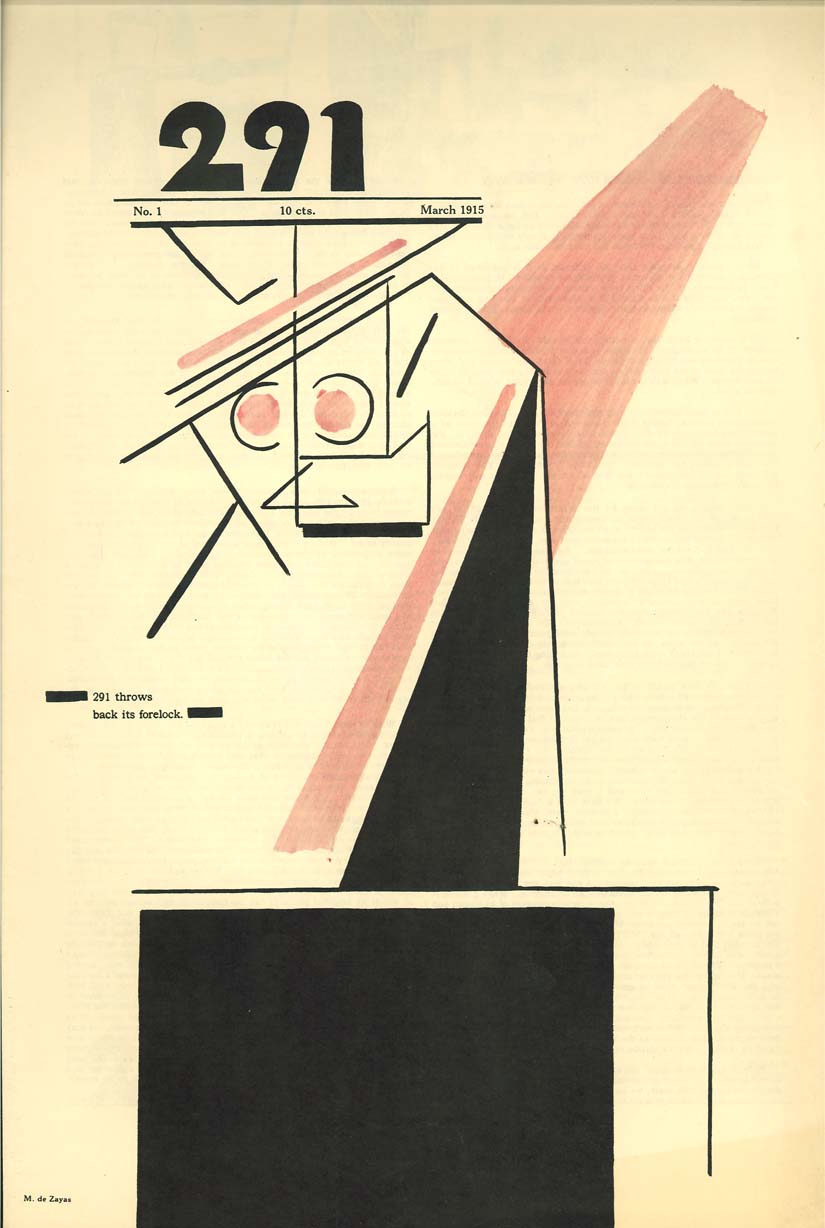

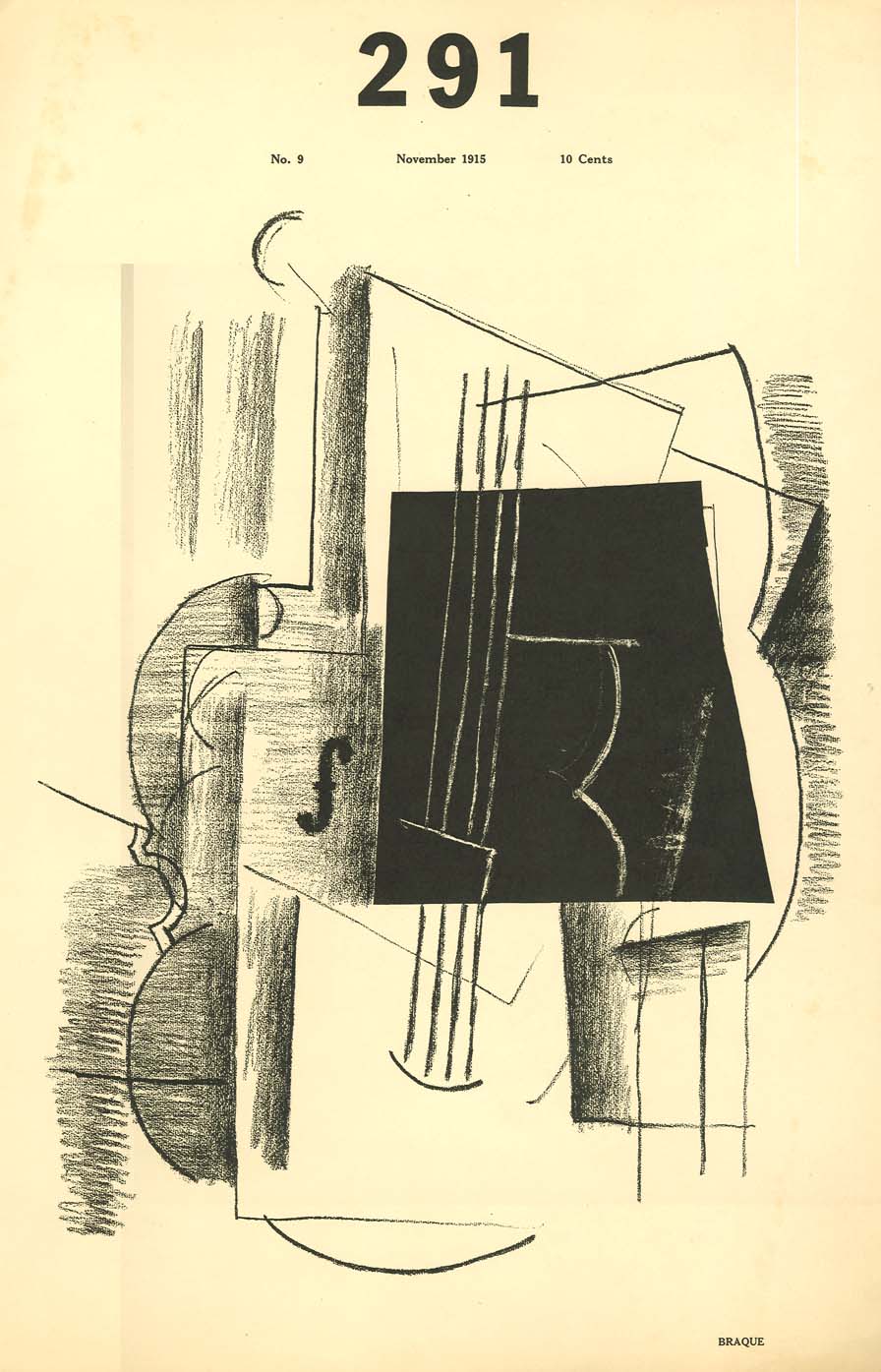

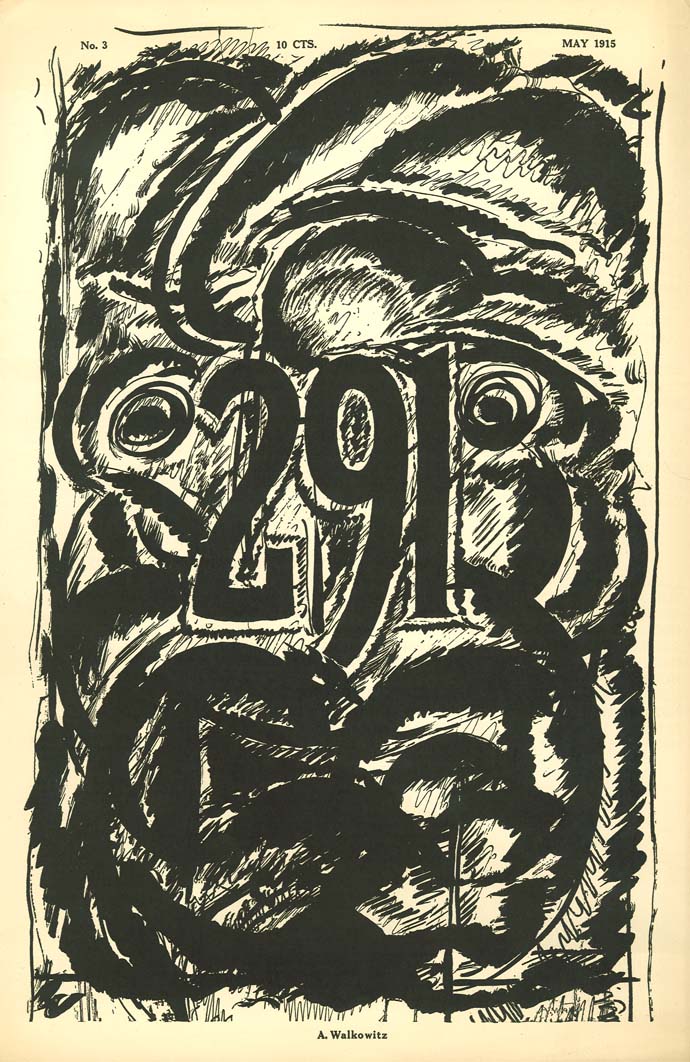

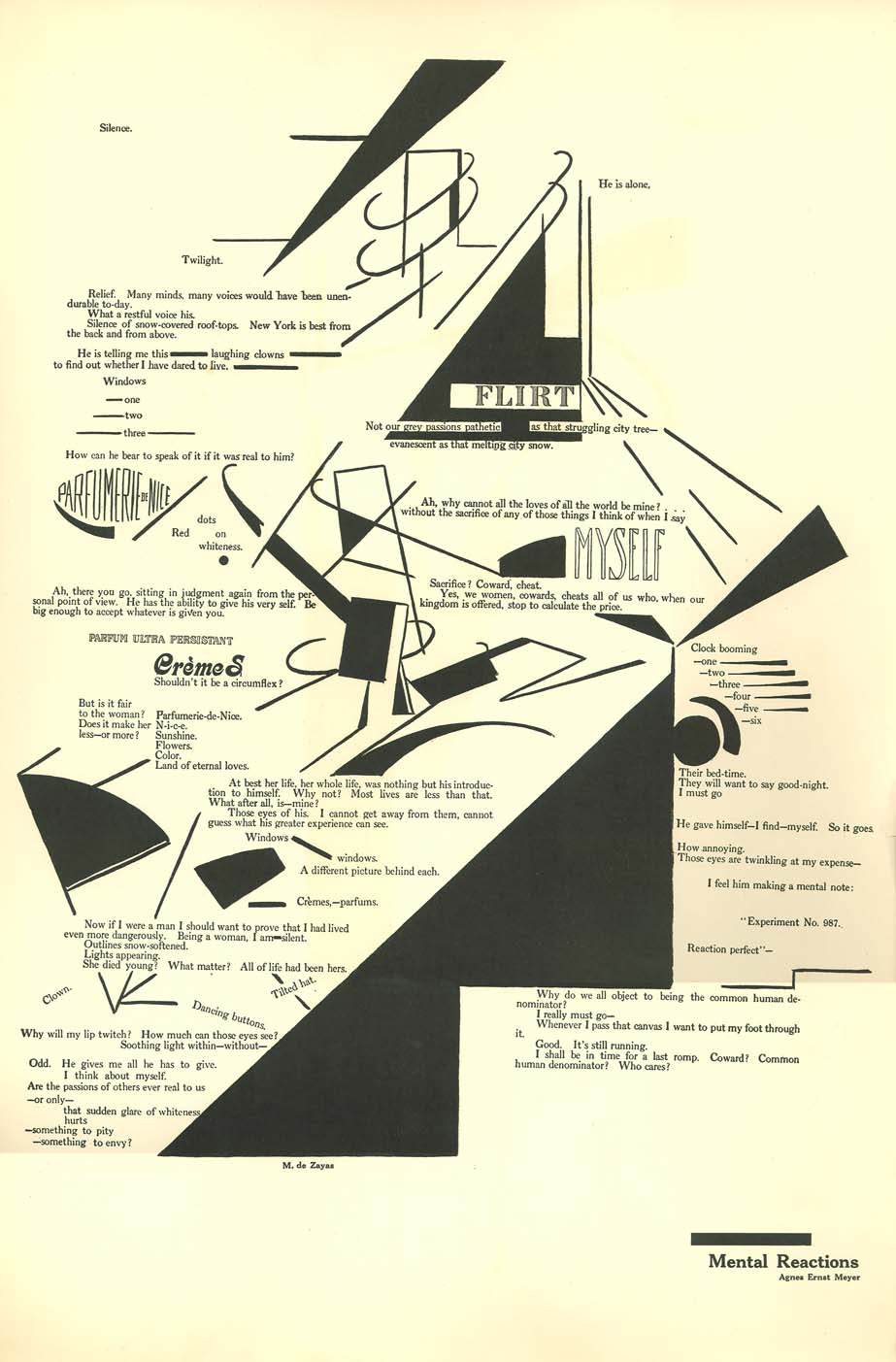

Despite this inglorious end, 291 is notable not only for its proto-dada status—and for featuring the work of modernists like Georges Braque, Guillaume Apollinaire, and later Dada and Surrealist artist Francis Picabia; the magazine also “occupies an interesting position among the journals of modernist art” as “the first magazine to style itself as a work of art in its own right.” You can get a sense of its artistry in the covers you see here, and download every issue of the magazine at Ubuweb or at the University of Iowa’s International Dada Archive. You’ll also see the magazine’s unusual format—from odd little topical items of the sort you’d find in a local newspaper to fascinating visual poetry like “Mental Reactions,” below, by Agnes Ernst Meyer. What we can’t get from the digital copies, unfortunately, is the full sense of 291’s “dramatic form” in its “gigantic folio format.”

The modernist journal “took its original inspiration from Apollinaire’s Soirées de Paris,” a journal founded in 1912 by the French poet and critic and his friends, “emphasizing caligrammatic texts and an abstracted kind of satirical drawing.” And though 291 may have had a very limited reach during its material existence, its influence continued into the era of Dada when Francis Picabia styled his own journal, 391, after Steiglitz’s publication. “Published 1917–1924 in Barcelona, New York, Zürich, and Paris in nineteen issues,” writes Booktryst, 391 helped Picabia distribute his own take on Dada, until he denounced the movement in 1921 and “issued a personal attack against [Surrealist Andre Breton] in the final issue.” The University of Iowa also hosts digital versions of all 19 issues of Picabia’s 391, which you can view and download here.

Related Content:

Three Essential Dadaist Films: Groundbreaking Works by Hans Richter, Man Ray & Marcel Duchamp

The ABCs of Dada Explains the Anarchic, Irrational “Anti-Art” Movement of Dadaism

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

Leave a Reply