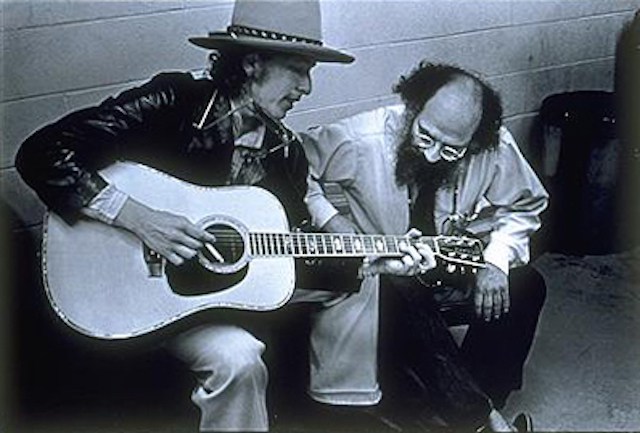

Image via Elisa Dorman, Wikimedia Commons

Whatever other criteria we use to lump them together—shared aims of psychedelic consciousness-expanding through drugs and Eastern religion, frank explorations of alternative sexualities, anti-establishment cred—the Beats were each in their own way true to the name in one very simple way: they all collaborated with musicians, wrote song or poems as songs, and saw literature as a public, performative art form like music.

And though I suppose one could call some of their forays into recorded music gimmicky at times, I can’t imagine Jack Kerouac’s career making a whole lot of sense without Bebop, or Burroughs’ without psychedelic rock and tape and noise experimentation, or Ginsberg’ without… well, Ginsberg got into a little bit of everything, didn’t he? Whether writing calypsos about the CIA, performing and recording with The Clash, showing up on MTV with Philip Glass and Paul McCartney…. He never worked with Kanye, but I imagine he probably would have.

For each of these artists, the medium delivered a message. Kerouac’s odes to jazz, loneliness, and wanderlust; Burroughs’ dark, paranoid prophecies about government control; and Ginsberg’s anti-war jeremiads and insistent pleas for peace, freedom, tolerance, and enlightenment. Ever the trickster and teacher, Ginsberg often used humor to disarm his audience, then went in for the kill, so to speak. We may find no more pointed an example of this comedic pedagogy than his 1981 song, “Do the Meditation Rock,” recorded in 1982 as a shambling folk-rock jam below with guitarist Steven Taylor, and members of Bob Dylan’s touring band—including Dylan himself making a rare appearance on bass.

As the story goes, according to Hank Shteamer at Rolling Stone, Ginsberg was in Los Angeles and “eager to book some studio time. Dylan obliged, and agreed to foot the bill for the studio costs on the condition that Ginsberg would pay the musicians. The two met at Dylan’s Santa Monica studio and, as Taylor remembers it, jammed for 10 hours.” Many more recordings from that session made it onto the recently released The Last World on First Blues, which also includes contributions from Jack Kerouac’s musical partner David Amram, folk legend Happy Traum, and experimental cellist, singer, and disco producer Arthur Russell.

See Ginsberg, Taylor, Russell, and Ginsberg’s partner Peter Orlovsky (meditating), perform the song above on a PBS special called “Good Morning, Mr. Orwell,” created in 1984 by Korean video artist Naim June Paik. As Ginsberg explains it in the liner notes to his collection Holy Soul, Jelly Roll, the song came together after his own meditation training in the late seventies, when the poet got the okay from his Buddhist teacher Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche (founder of Naropa University) to “show basic meditation in his traditional classrooms or groups at poetry readings”—his goal, he says, to “knock all the poets out with sugar-coated dharma.”

Christmas Eve, I stopped in the middle of the block at a stoop and wrote the words down, notebook on my knee. I figured that if anyone listened to the words, they’d find complete instructions for classical sitting practice, Samatha-Vipassana (“Quieting the mind and clear seeing”). Some humor in the form, it doesn’t have to be taken over-seriously, yet it’s precise.

You may have noticed the familiar cadence of the chorus; it’s a take-off, he says, on “I Fought the Law,” recorded in 1977 by his soon-to-be musical partners, The Clash. In the live version below at New York’s Ukranian National Home, the song gets a more stripped-down, punk rock treatment with Tom Rogers on guitar. Like many a wandering bard, Ginsberg changes and adapts the lyrics slightly to the venue and occasion. See the Allen Ginsberg Project for several published versions of the lyrics and his changes in this rendition.

Apart from the basic meditation instructions, which are easy to follow in writing and song, Ginsberg’s “Do the Meditation Rock” had another message, specific to his understanding of the power of meditation; it can change the world, in spite of “a holocaust” or “Apocalypse in a long red car.” As Ginsberg speak/sings, “If you sit for an hour or a minute every day / you can tell the Superpower, sit the same way / you can tell the Superpower, watch and wait.” No matter how bad things seem, he says, “it’s never too late to stop and meditate.” Hear another recorded version of the song below from Holy Soul, Jelly Roll, recorded live in Kansas City by William S. Burroughs in 1989.

Related Content:

Allen Ginsberg Recordings Brought to the Digital Age. Listen to Eight Full Tracks for Free

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply