On May 1st, 2016, Maurice Ravel’s masterful orchestral composition Boléro entered the public domain, which means we may be hearing a lot more of the piece, first written and performed in 1928 as a ballet commissioned by Russian dancer Ida Rubenstein. Then again, it’s not like Boléro hasn’t fully permeated the public’s domain for decades, regardless of its copyright status.

Audiences swooned as British ice dancers Torvill and Dean won the gold at the 1984 Winter Olympics in Sarajevo with a perfect score-performance to Boléro; both Jeff Beck and Frank Zappa have covered it; Boléro famously scored a sex scene in 1979’s sleazy comedy 10; it popped up in 2014’s Spider-Man 2; and it even provided the title of a film, 1934’s Bolero, which culminated in the leads dancing to Ravel’s composition….

If you happened to have missed all of these cultural moments, you’ve still heard Boléro, with its unmistakable flute and piccolo melody and persistently rapping snare drum. (Maybe you, and your tot, saw seven chickens dance to Boléro on Sesame Street.)

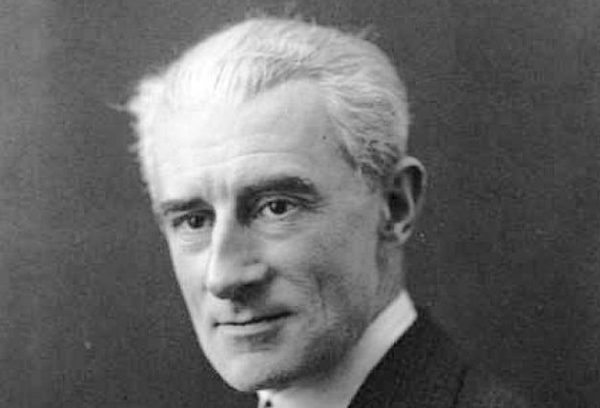

Boléro is not only Ravel’s most famous composition, but perhaps one of the most well-known pieces of classical music ever written. “Famous to historians and record-books for ostensibly containing the longest-sustained single crescendo anywhere in orchestral repertory,” writes Allmusic, and “famous to musicians and music lovers for being both the most repetitive 15 minutes of music they are likely to play/hear and also one of the most absolutely well-composed.” So repetitive is Boléro that it has been cited as evidence that Maurice Ravel suffered from Alzheimer’s when he wrote it.

I find this explanation of Boléro unconvincing, primarily because of its aforementioned “well-composed” quality. This is no musical perseveration, the symptom of a decaying mind, but an intentional exercise—as is so much modern music since Ravel—in finding beauty and variation in sameness. We hear it in the minimalism of composers like Steve Reich, or the droning beats of Kraftwerk and Can. In fact, classical review magazine Gramophone invokes Krautrock-style repetition in its description of Boléro’s drive “toward motorik self-oblivion.” The piece “is about developing a single moment in time, obsessively rethought/re-shaded/redrawn/revisited, revealed through shifting perspectives on itself.”

Gramophone’s thorough documentation of Boléro’s recording history details the ways in which a succession of conductors and orchestras have approached the piece’s complex interplay of sameness and difference, beginning with one of the very first recordings, conducted by Ravel himself, in 1930. Leading the Orchestre des Concerts Lamoureux in a session for Polydor, Ravel was in poor health, and perhaps indeed suffering from some form of dementia. (Two years later, an auto accident worsened his condition; Ravel died in 1937 after an unsuccessful brain surgery.) His “conducting technique” in the 1930 recording “falls far short” in comparison to other recorded versions, writes Gramophone in their tepid review.

Nonetheless, this version represents a “historical curio” and an opportunity to hear the composer preside over his own interpretation of this enthralling piece of music. You can hear Ravel’s recording above or on the album Ravel: Ses Amis et Ses Interpretes, available on Spotify (get Spotify’s software here).

Related Content:

Hear Ravel Play Ravel in 1922

Hear Debussy Play Debussy: A Vintage Recording from 1913

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

It’s Bolero, without the accent on the e.

Oh really? Why do you say that? Cambridge Quarterly, Cambridge Companion to Ravel, Warner Classics, Sony Classical, and several others all use accented spelling…

Boléro (French)/Bolero (Spanish)

In the score: Bolero http://imslp.eu/Files/imglnks/euimg/5/5c/IMSLP01578-Ravel_-_Bolero__Full_Score_Durand_1929_.pdf

Thanks for clarifying, Miguel.

Hah! I *knew* it!!!!

This recording features a trombone pitched in “C,” not Bb. Ravel usually knew what he was doing in terms of orchestration, and his Bolero lies, um, awkwardly at best on a Bb trombone.

C trombones were available and used at least sporadically in France back in the days of this piece’s premier. Listen to the clarity of that first high Db, (a nice, solid note on a C trombone, and a fluffy note on a Bb), and the relative fuzziness of the final low Db (in 7th position on a C). Aside from that low Db, this whole piece lies much more logically on a C trombone. The final tutti glissandi as another example lie beautifully on a C, and sound pretty darn good on this recording.

Thanks so much for posting this recording and giving me a good excuse to fire up that propane torch! :)

This is gonna be fun.