One outcome of the upcoming “Brexit” vote, we’re told, might free the UK to pursue its own unfettered destiny, or might plunge it into isolationist decline. The economic issues are beyond my ken, but as a reader and student of English literature, I’ve always been struck by the fact that the oldest poem in English, Beowulf, shows us an already internationalized Britain absorbing all sorts of European influences. From the Germanic roots of the poem’s Anglo-Saxon language to the Scandinavian roots of its narrative, the ancient epic reflects a Britain tied to the continent. With pagan, native traditions mingled with later Christian echoes, and local legends with those of the Danes and Swedes, Beowulf preserves many of the island nation’s polyglot, multi-national origins.

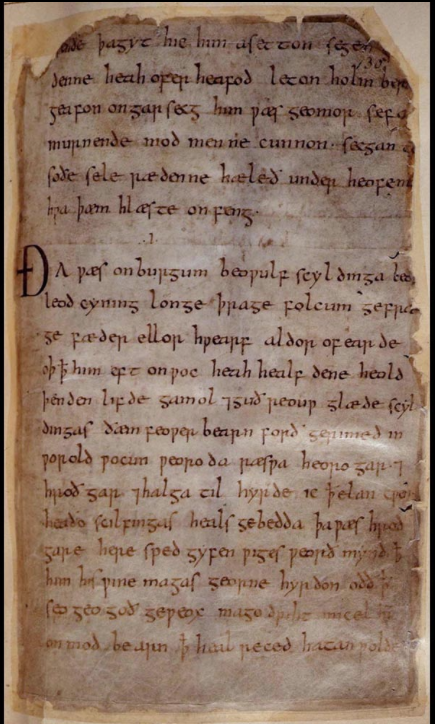

Irish poet Seamus Heaney—whose work engaged with the ironies and complications of tribalism and nationalism—had a deep respect for Beowulf; in the introduction to his translation of the poem, Heaney describes it as a tale “as elaborate as the beautiful contrivances of its language. Its narrative elements may belong to a previous age but as a work of art it lives in its own continuous present, equal to our knowledge of reality in the present time.” Though we’ve come to think of it as an essential work of English literature, Beowulf might have disappeared into the mists of history had not the only manuscript of the poem survived “more or less by chance.” The “unique copy,” writes Heaney, “(now in the British Library) barely survived a fire in the eighteenth century and was then transcribed and titled, retranscribed and edited, translated and adapted, interpreted and taught, until it has become an acknowledged classic.”

Now, the British Library’s digitization of that sole manuscript allows us to peel back the layers of canonization and see how the poem first entered a literary tradition. Originally “passed down orally over many generations, and modified by each successive bard,” writes the British Library, Beowulf took this fixed form when “the existing copy was made at an unknown location in Anglo-Saxon England.” Not only is the location unknown, but the date as well: “its age has to be calculated by analyzing the scribes’ handwriting. Some scholars have suggested that the manuscript was made at the end of the 10th century, others in the early decades of the 11th, perhaps as late as the reign of King Cnut, who ruled England from 1016 until 1035.”

These scholarly debates may not interest the average reader much. The poem survived long enough to be written down, then became known as great literature these many centuries later, because the rich poetic language and the compelling story it tells captivate us still. Nonetheless, though we may all know the general outlines of its hero’s contest with the monster Grendel and his mother, many of the cultural concepts from the world of Beowulf strike modern readers as totally alien. Likewise the poem’s language, Old English, resembles no form of English we’ve encountered before. Scholars like J.R.R. Tolkien and poets like Heaney have done much to shape our appreciation for the ancient work, and we might say that without their interventions, it would not live, as Heaney writes, “in its own continuous present” but in a distant, unrecognizable past.

You can hear Heaney read his translation of the poem on Youtube. Read Tolkien’s famous essay on the poem here, and hear it read in its original language at our previous post. Learn more about the single manuscript that preserved the epic poem for posterity at the British Library’s website, and see it for yourself in their digital archive.

Find Beowulf listed in our collection, 800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices.

Related Content:

Seamus Heaney Reads His Exquisite Translation of Beowulf and His Memorable 1995 Nobel Lecture

Hear Beowulf Read In the Original Old English: How Many Words Do You Recognize?

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Thank you for sharing. In the Beginning of 2000 in Victoria, BC I heard a bard presenting Beowulf how it might have been when it was created and noticed, how one can perceive the meaning without understanding the vocabular. It reminded me of childhood memories of Elias Canetti who grew up with a vocabulary consisting of many languages without dicerning their national origin.

I would also strongly recommend watching the BBC documentary The Search for Beowulf by Michael Wood. It is an excellent introduction to Beowulf the poem, time and place of that long ago time, there is also an excellent “telling” by Julian Glover in an reconstruction of an old Anglo-Saxon mead hall.