The idea of “the author,” wrote Roland Barthes, “rules in manuals of literary history, in biographies of writers, in magazine interviews, and even in the awareness of literary men, anxious to unite, by their private journals, their person and their work.” We see this anxiety of authorship in much of Walt Whitman’s personal correspondence. The poet, “could be surprisingly anxious about his own disappearance,” writes Zachary Turpin in the introduction to a recently re-discovered series of Whitman essays called “Manly Health and Training.”

Whitman, however, was just as often anxious to disassociate his person from his work, whether juvenile short stories or his copious amount of journalism and occasional pieces. Originally published in the New York Atlas between 1858 and 1860, “Manly Health and Training”—“part guest editorial, part self-help column”—may indeed represent some of the work Whitman wished would disappear in his late-in-life attempts at “careerist revisionism.” As it happens, reports The New York Times, these articles did just that until Turpin, a graduate student in English at the University of Houston, found the essays last summer while browsing articles written under various journalistic pseudonyms Whitman used.

The work in question appeared under the name “Mose Velsor,” and it’s worth asking, as Barthes might, whether we should consider it by the poetic figure we call “Whitman” at all. Though we encounter in these occasionally “eyebrow-raising” essays the “more-than-typically self-contradictory Whitman,” Turpin comments, “these contradictions display little of the poetic dialecticism of Leaves of Grass”—first published, without the author’s name, in 1855.

The essays are piecemeal distillations of “a huge range of topics” of general interest to male readers of the time—in some respects, a 19th century equivalent of Men’s Health magazine. And yet, argues Ed Folsom, editor of The Walt Whitman Quarterly—which has published the nearly 47,000 word series of essays online—“One of Whitman’s core beliefs was that the body was the basis of democracy. The series is a hymn to the male body, as well as a guide to taking care of what he saw as the most vital unit of democratic living.” These themes are manifest along with the robust homoeroticism of Whitman’s poetry:

We shall speak by and by of health as being the foundation of all real manly beauty. Perhaps, too, it has more to do than is generally supposed, with the capacity of being agreeable as a companion, a social visitor, always welcome—and with the divine joys of friendship. In these particulars (and they surely include a good part of the best blessings of existence), there is that subtle virtue in a sound body, with all its functions perfect, which nothing else can make up for, and which will itself make up for many other deficiencies, as of education, refinement, and the like.

David Reynolds, professor of English at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, concurs: “there’s a kind of health-nut thing about ‘Leaves of Grass’ already. This series sort of codifies it and expands on it, giving us a real regimen.” To that end, two of “Mose Velsor”’s prominent topics are diet and exercise, and whether we consider “Manly Health and Training” a prose addendum to Whitman’s first book or mostly work-for-hire on a range of topics in his general purview, some of the advice, like the poetry, can often sound particularly modern, while at the same time preserving the quaintness of its age.

Anticipating the Paleo craze, for example, Whitman writes, “let the main part of the diet be meat, to the exclusion of all else.” His diet advice is far from systematic from essay to essay, yet he continually insists upon lean meat as the foundation of every meal and refers to beef and lamb as “strengthening materials.” The “simplest and most natural diet,” consists of eating mainly meat, Whitman asserts as he casts aspersions on “a vegetarian or water-gruel diet.” Whitman issues many of his dietary recommendations in the service of vocal training, recommending that his readers “gain serviceable hints from the ancients” in order to “give strength and clearness to their vocalizations.”

Aspirants to manliness should also attend to the ancients’ habit of frequenting “gymnasiums, in order to acquire muscular energy and pliancy of limbs.” Many of Whitman’s training regimens conjure images from The Road to Wellville or of stereotypical 19th-century strong men with handlebar mustaches and funny-looking leotards. But he does intuit the modern identification of a sedentary lifestyle with ill health and premature death, addressing especially “students, clerks, and those in sedentary or mental employments.” He exhorts proto-cubical jockeys and couch potatoes alike: “to you, clerk, literary man, sedentary person, man of fortune, idler, the same advice. Up!”

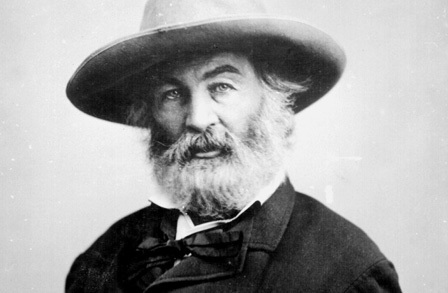

Whitman’s “warnings about the dangers of inactivity,” writes The New York Times, “could have been issued from a 19th-century standing desk,” a not unlikely scenario, given the many authors from the past who wrote on their feet. But should we picture Whitman himself issuing these proclamations on “Health and Training”? No image of the man himself, with cocked elbow and cocked hat, is affixed to the essays. The pseudonymous byline may be no more than a convention, or it may be a desire to inhabit another persona, and to distance the words far from those of “Walt Whitman.”

Did Whitman consider the essays hackwork—populist pabulum of the kind struggling writers today often crank out anonymously as “sponsored content”? The series, Turpin writes “is un-Whitmanian, even unpoetic,” its function “fundamentally utilitarian, a physiological and political document rooted in the (pseudo)sciences of the era.” Not the sort of thing one imagines the highly self-conscious poet would have wanted to claim. “During his lifetime,” Whitman “wasted no time reminding anyone of this series,” likely hoping it would be forgotten.

And yet, it’s interesting nonetheless to compare the exaggerated masculinity of “Manly Health and Training” with much of the belittling personal criticism Whitman received in his lifetime, represented perfectly by one Thomas Wentworth Higginson. This critic and harsh reviewer included Whitman’s “priapism,” his serving as a nurse during the Civil War rather than “going into the army,” and his “not looking… in really good condition for athletic work” as reasons why the poet “never seemed to me a thoroughly wholesome or manly man.”

In addition to thinly veiled homophobia, many of Higginson’s comments suggested, write Robert Nelson and Kenneth Price, that “as a social group, working-class men did not and could not possess the qualities of true manliness.” Perhaps we can read these early Whitman editorials, pseudonymous or not, as democratic instructions for using masculine health as a great social leveler and means to “make up for many other deficiencies, as of education, refinement, and the like.” Or perhaps “Manly Health and Training” was just another assignment—a way to pay the bills by peddling popular male wish-fulfillment while the poet waited for the rest of the world to catch up with his literary genius.

Related Content:

Free Online Literature Courses

Orson Welles Reads From America’s Greatest Poem, Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” (1953)

Mark Twain Writes a Rapturous Letter to Walt Whitman on the Poet’s 70th Birthday (1889)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply