It is widely accepted among scholars that the first few books of the Bible—including, of course, Genesis, with its creation myths and flood story—are a patchwork of several different sources, pieced together by so-called redactors. This “documentary hypothesis” identifies the literary characteristics of each source, and attempts to reconstruct their different theological and political contexts. Primarily refined by German scholars in the late nineteenth century, the theory is very persuasive, but can also seem pretty schematic and dry, robbing the original texts of much of their liveliness, rhetorical power, and ancient strangeness.

Another German scholar, Hermann Gunkel, approached Genesis a little differently. “Everyone knows”—write the editors of a scholarly collection on the foundational Biblical text—Gunkel’s “motto”: “Genesis ist eine Sammlung von Sagen”—“Genesis is a collection of popular tales.” Rather than reading the various stories contained within as historical narratives or theological treatises, Gunkel saw them as redacted legends, myths, and folk tales—as ancient literature. “Legends are not lies,” he writes in The Legends of Genesis, “on the contrary, they are a particular form of poetry.”

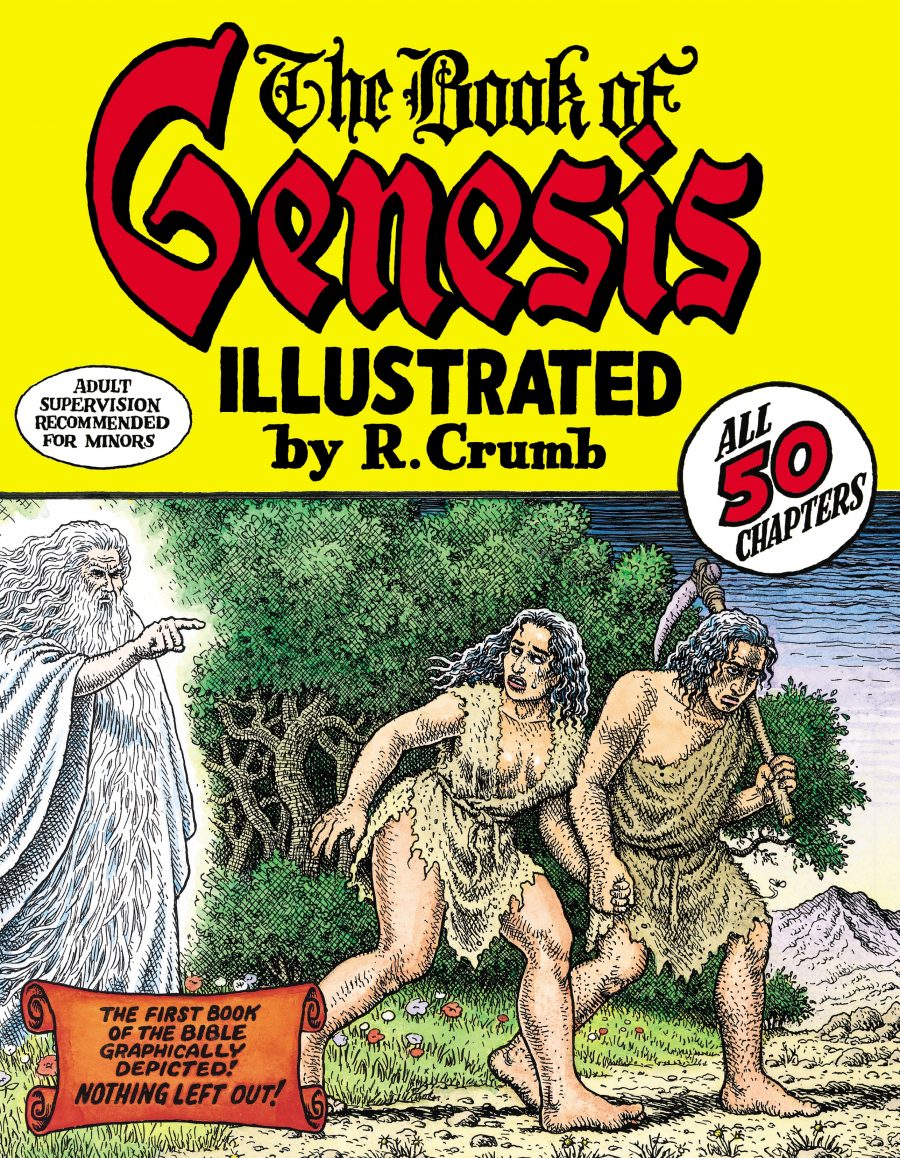

Such was the approach of cartoonist and illustrator Robert Crumb, who took on illustrating the entire book of Genesis, “a text so great and so strange,” he says, “that it lends itself readily to graphic depictions.” In the short video above, Crumb describes the creation narrative in the ancient Hebrew book as “an archetypal story of our culture, such a strong story with all kinds of metaphorical meaning.” He also talks about his genuine respect and admiration for the stories of Genesis and their origins. “You study ancient Mesopotamian writings,” says Crumb, “and there’s all of these references in the oldest Sumerian legends about the tree of knowledge” and other elements that appear in Genesis, mixed up and redacted: “That’s how folk legends and all that shit evolve over centuries.”

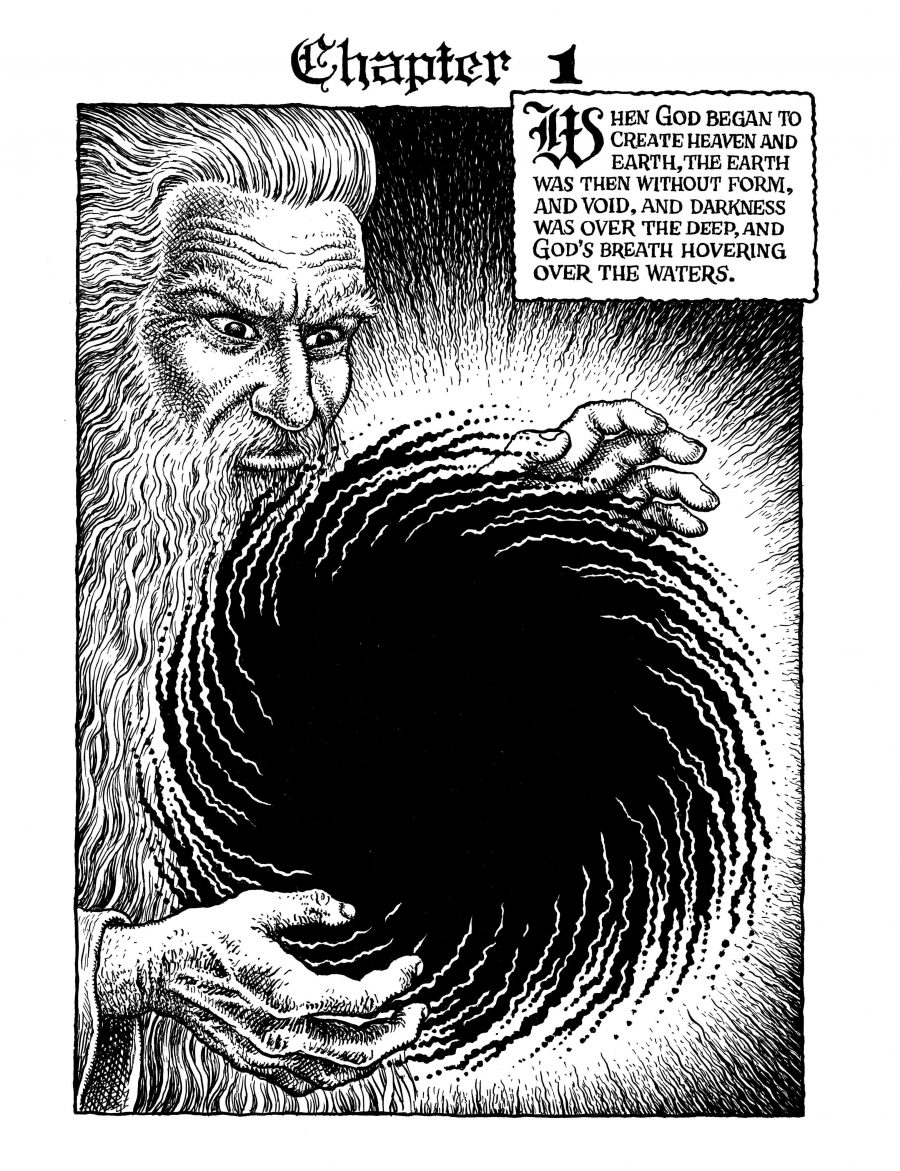

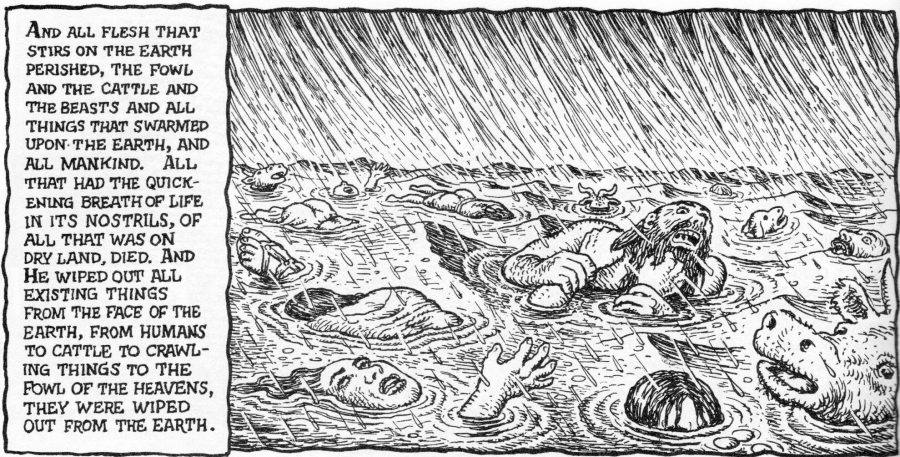

The Biblical book first struck Crumb as “something to satirize,” and his initial approach leans on the irreverent, scatological tropes we know so well in his work. But he instead decided to produce a faithful visual interpretation of the text just as it is, illustrating each chapter, all 50, word for word. The result, writes Colin Smith at Sequart, is “idiosyncratic, tender-hearted and ultimately inspiring.” It is also a critical visual commentary on the text’s central character: Crumb’s God “is regularly, if not exclusively, portrayed as an unambiguously self-obsessed and bloodthirsty despot, terrifying in his demands, terrifying in his brutality.” Arguably, these traits emerge from the stories unaided, yet when we’re told, for example, that “The Lord regretted having made man on Earth and it grieved him in his heart,” Crumb “shows us nothing of regret and grief, but rather a furious old dictator apparently tottering on the edge of madness.”

“It’s not the evil of men that Crumb’s concerned with,” writes Smith, “so much as the psychology of a creature who’d slaughter an entire world.” In that interpretation, he echoes critics of the Bible’s theology since the Enlightenment, from Voltaire to Christopher Hitchens. But he doesn’t shy away from graphic depictions of human brutality, either. Crumb’s move away from satire and decision to “do it straight,” as he told NPR, came from his sense that the sweeping, violent mythology and “soap opera” relationships already lend themselves “to lurid illustration”—his forté. Originally intending to do just the first couple chapters “as a comic story,” he soon found he had a market for all 50 and “stupidly said, ‘okay, I’ll do it.’” The work—undertaken over four years—proved so exhausting, he says he “earned every penny.”

Does Crumb himself identify with the religious traditions in Genesis? Raised a Catholic, he left the church at 16: “I have my own little spiritual quest,” Crumb says, “but I don’t associate it with any particular traditional religion. I think that the traditional Western religions all are very problematic in my view.” That said, like many nonreligious people who read and respect religious texts, he knows the Bible well—better, it turned out, than his editor, a self-described expert. “I just illustrate it as it’s written,” said Crumb, “and the contradictions stand.”

When I first illustrated that part, the creation, where there’s basically two different creation stories that do contradict each other, and I sent it to the editor at Norton, the publisher, who told me he was a Bible scholar. And he read it, and he said wait a minute, this doesn’t make sense. This contradicts itself. Can we rewrite this so it makes sense? And I said that’s the way it’s written. He said, that’s the way it’s written? I said, yeah, you’re a Bible scholar. Check it out.

Crumb invites us all to “check it out”—this collection of archetypal legends that inform so much of our politics and culture, whether the bizarre and costly creation of a fundamentalist “Ark Park” (“dinosaurs and all”), or the Biblical epics of Cecil B. DeMille or Darren Aronofsky, or the poetry of John Milton, or the interpretive illustrations of William Blake. Whether we think of it as history or myth or some patchwork quilt of both, we should read Genesis. R. Crumb’s illustrated version is as good—or better—a way to do so as any other. See more of his illustrations at The Guardian and purchase his illustrated Genesis here.

Related Content:

A Short History of America, According to the Irreverent Comic Satirist Robert Crumb

R. Crumb’s Vibrant, Over-the-Top Album Covers (1968–2004)

R. Crumb Describes How He Dropped LSD in the 60s & Instantly Discovered His Artistic Style

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

I’ve had this book for ages and it’s just a beautiful work of art. There’s a lot of weirdness that Crumb re-discovers that has been hidden after centuries of Bible School simplification. This plus Chester Brown’s religious books are ideal reading, no matter where you are on the religious spectrum. (Unless you’re humorless and offended at everything.)

i love it. there was no form and darkness was over the waters.

water is totally a form. the contradictions sand, as Mr. Crumb duly notes.

Re-read the passage. Ask the Holy Spirit for guidance. Here is what the passage doesn’t say, ‘Before God could create the heavens and the earth, God created the “waters“ ‘, but implies it.

Just asked the Holy Spirit for guidance. There’s a thunderstorm over the house right now. I suppose it’s busy implying something.

Thoroughly enjoyed your article. I keep his Book of Genesis on my desk. To me, the brilliance of it is, as you said, the overlay of illustration on the words.

This is one of my favorite representations of Genesis.

All in all, wouldn’t Cain have beat abel down with one of His agricultural tools, like a hoe, or an axe, or a machete? Why just a rock?

Because he didn’t want to place his hands on the murder weapons once he murdered his brother. Thoughts?

It looks like a cartoon of Thor. Only meaner.