In the years after World War II, the CIA made use of jazz musicians, abstract expressionist painters, and experimental writers to promote avant-garde American culture as a Cold War weapon. At the time, downward cultural comparisons with Soviet art were highly credible.

Many years of repressive Stalinism and what Isaiah Berlin called “the new orthodoxy” had reduced so much Russian art and literature to didactic, homogenized social realism. But in the years following the first World War and the Russian Revolution, it would not have been possible to accuse the Soviets of cultural backwardness.

The first three decades of the twentieth century produced some of the most innovative art, film, dance, drama, and poetry in Russian history, much of it under the banner of Futurism, the movement begun in Italy in 1909 by F.T. Marinetti. Like the Italian Futurists, these avant-garde Russian artists and poets were, writes Poets.org, “preoccupied with urban imagery, eccentric words, neologisms, and experimental rhymes.” One of the movement’s most inventive members, Velimir Khlebnikov, wrote poetry that ranged from “dense and private neologisms to exotic verseforms written in palindromes.” Most of his poetry “was too impenetrable to reach a popular audience,” and his work included not only experiments with language on the page, but also avant-garde industrial sound recording.

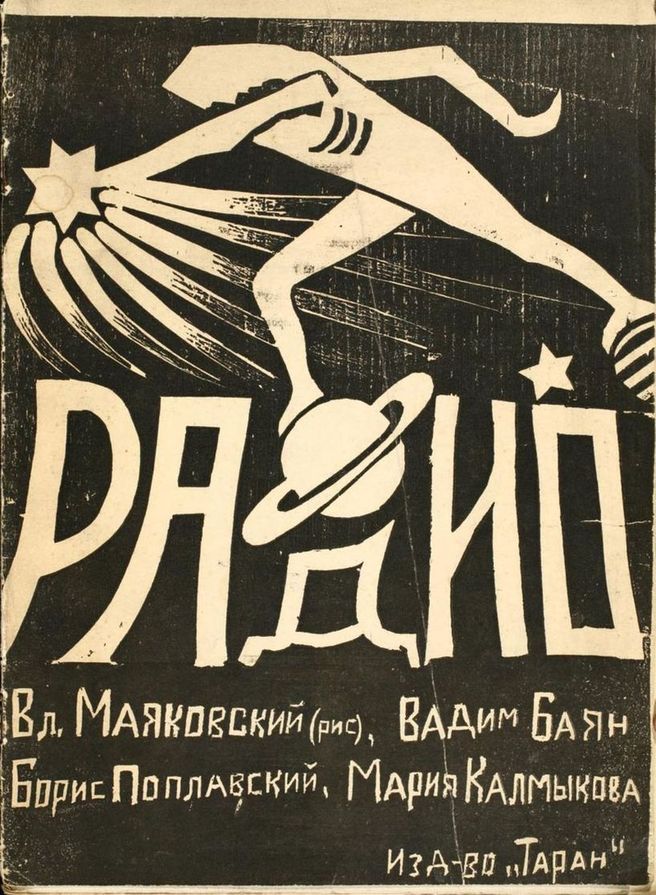

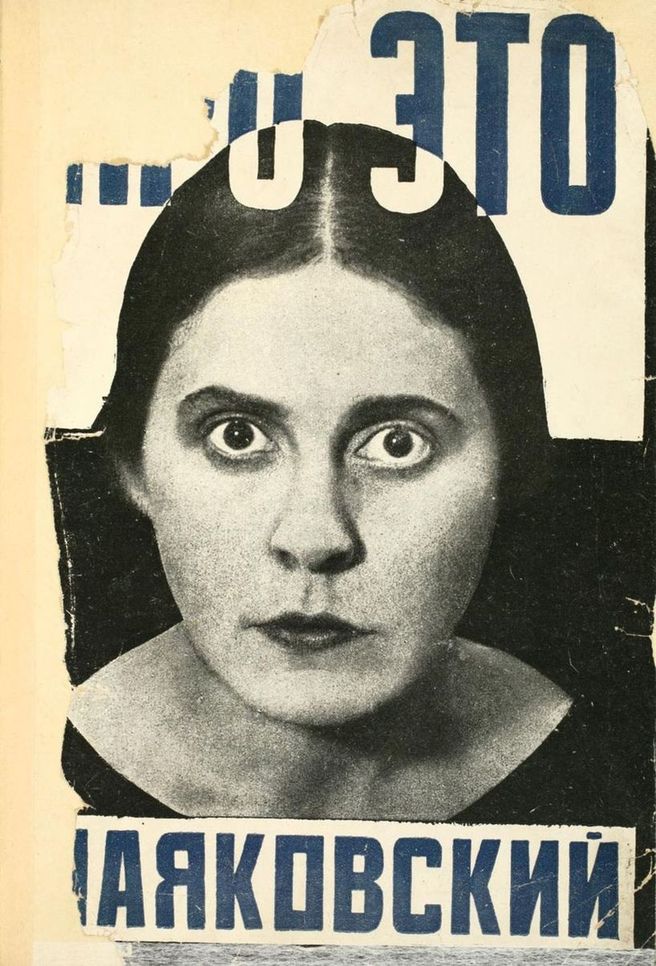

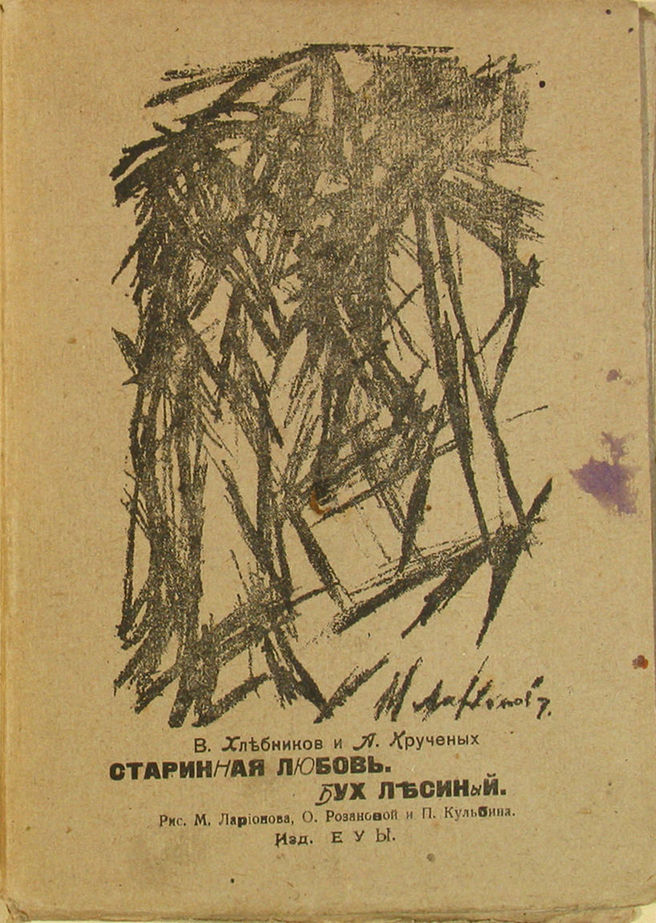

Khlebnikov’s experiments in linguistic sound and form became known as “Zaum,” a word that can be translated as “transreason,” or “beyond sense.” He pioneered his techniques with another major Futurist poet, Aleksei Kruchenykh, who may have been, writes Monoskop, “the most radical poet of Russian Futurism.” The most famous name to emerge from the movement, Vladimir Mayakovsky, embodied Futurism’s confident individualism, his poetics “a mixture of extravagant exaggerations and self-centered and arduous imagery.” Mayakovsky made a name for himself as an actor, painter, poet, filmmaker, and playwright. Even Stalin, who would soon preside over the suppression of the Russian avant-garde, called Mayakovsky after his death in 1930 “the best and most talented poet of the Soviet epoch.”

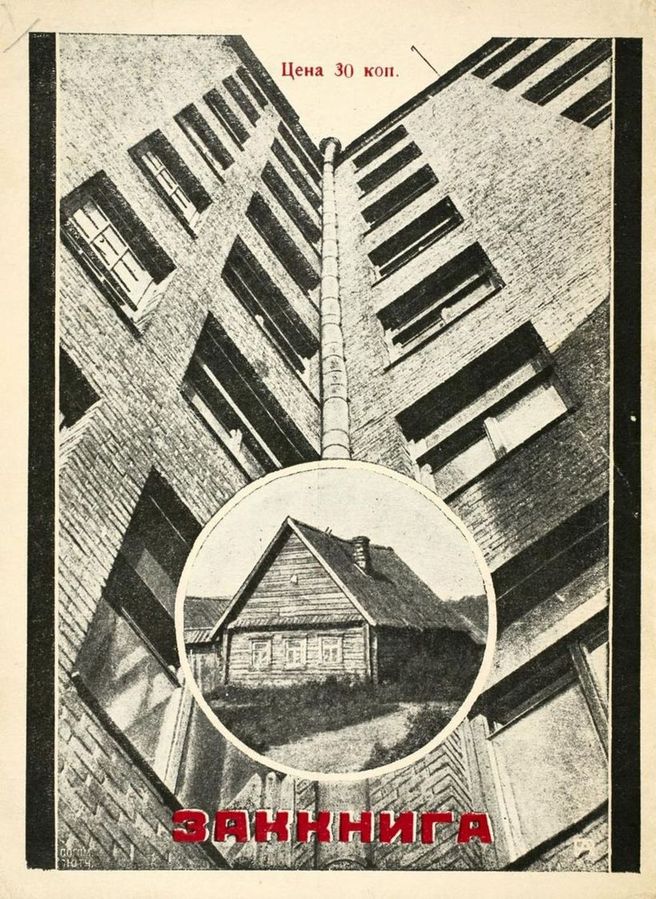

Monoskop points us toward a sizable online archive of 144 digitally scanned Futurist publications, including major works by Khlebnikov, Kruchenykh, Mayakovsky, and other Futurist poets, writers, and artists. There’s even a critical essay by the imposing Russian painter and founder of the austere school of Suprematism, Kazimir Malevich. All of the texts are in Russian, as is the site that hosts them—the State Public Historical Library of Russia—though if you load it in Google Chrome, you can translate the titles and the accompanying bibliographic information.

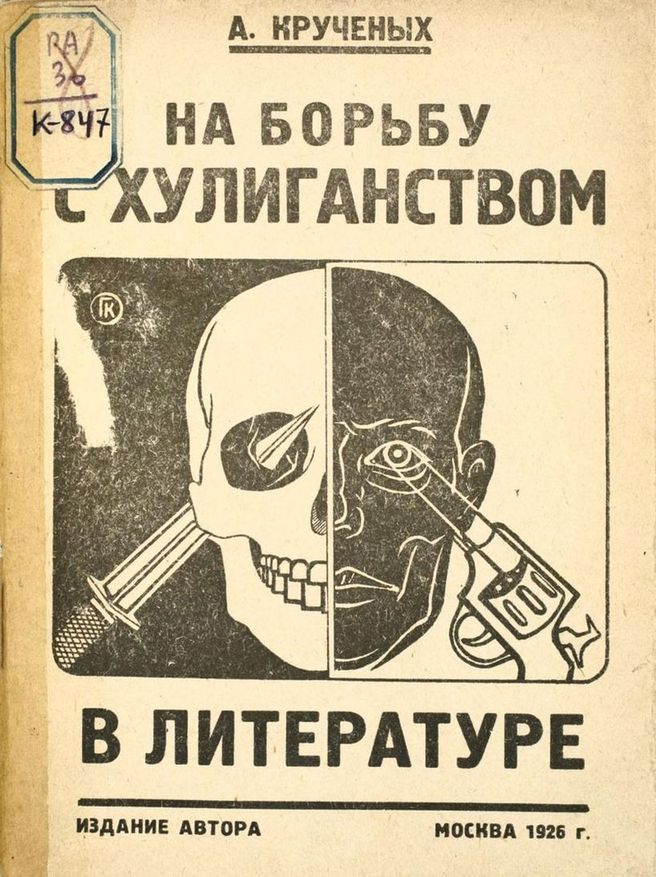

You can also download full pages in high-resolution. Many of the texts include strong visual elements, such as the cover at the top from a multi-author collection titled Radio, featuring Mayakovsky, whose own books include photo montages like the two further up. Just above, see the cover of Khlebnikov and Kruchenykh’s Vintage Love, which includes many more such sketches. And below, the cover of a 1926 book by Kruchenykh called On the Fight Against Hooliganism in Literature.

Although “state control was absolute throughout” Soviet history, these artists flourished before Trotsky’s fall in 1928, wrote Isaiah Berlin in his 1945 profile of Russian art; there was “a vast ferment in Soviet thought, which during those early years was genuinely animated by the spirit of revolt against, and challenge to, the arts of the West.” The Party came to view this period as “the last desperate struggle of capitalism” and the Futurists would soon be overthrown, “by the strong, young, materialist, earthbound, proletarian culture”—a culture imposed from above in the mid-30s by the Writers’ Union and the Central Committee.

Thus began the regrettable persecutions and purges of artists and dissidents of all kinds, and the movement toward the Stalinist personality cult and “collective work on Soviet themes by squads of proletarian writers.” But during the first quarter of the century, “a time of storm and stress,” Russian literature and art, Berlin adjudged, “attained its greatest height since its classical age of Pushkin, Lermontov, and Gogol.”

via Monoskop

Related Content:

Hear Russian Futurist Vladimir Mayakovsky Read His Strange & Visceral Poetry

Hear the Experimental Music of the Dada Movement: Avant-Garde Sounds from a Century Ago

Extensive Archive of Avant-Garde & Modernist Magazines (1890–1939) Now Available Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Thank you so very much for this incredible gift of free downloads of this extremely important Russian movement.

‑Feverous insomnia

William

Where did you find the download link?

Where is the download link, please!?

well, try the monoskop original messagge at the end

Me intereso siempre desde joven el movimiento ruso futurista prerevolucionario. ¿porque fue luego culturakmente incompatible con la Revolución — no solo con Stalin-?

Khlebnikov’s “avant-garde industrial sound recording” piece is actually not Khlebnikov, but a contemporary composition inspired by Khlebnikov from 2006. Do your research before posting.

Where is the download link, please??

http://elib.shpl.ru/ru/indexes/values/10040

Más que nada por ciertos conceptos marxistas (muy forzados y mal entendidos, en parte porque Marx no publicó en vida mucho de lo que pensó y escribió) como el “poder popular” o “dictadura proletaria”, que básicamente vendría a ser que los trabajadores del mundo establecieran una forma de organización nueva y distinta de la república que los burgueses habían construido en Francia, Estados Unidos y América Latina y que Napoleón semi-instaló en los países que conquistó. Este sería un nuevo orden; un nuevo tipo de Estado interino para asegurar que los burgueses no recuperaran lo usurpado.

Lenin a sostuvo que un partido proletario debía ser dirigido por una vanguardia ilustrada y revolucionaria para asegurar la victoria sobre la nobleza rusa y latifundistas, y posteriormente sobre los burgueses liberales y social-demócratas. Además, se propuso el centralismo democrático como mecanismo de toma de decisión. Todo eso, sumado a las tensiones tras la guerra civil, fue caldo de cultivo para cimentar más y más un Estadode tipo tiránico y dogmático. Cualquier cuerpo teórico que tuviese tintes de idealismo (contrario al realismo duro del marxismo ingenuo) o que fomentara exaltación del individuo por sobre la colectivización de la vida y los medios de producción.

El movimiento futurista (y en general el modernismo aplicado a la ingeniería, psicología y arquitectura) fue muy bien recibido por el gobierno, pero a lo largo de los años, se dio un giro al respecto (en parte por las purgas).Un buen trabajo al respecto es el del ruso Ross Wolfe:

https://thecharnelhouse.org/2011/11/22/the-graveyard-of-utopia-soviet-urbanism-and-the-fate-of-the-international-avant-garde/

Could someone please reupload this??

this is incredible! though i wish that someday these will be translated into English.

its easy to see these graphics as progressive but the message advocates a violence and a supression of certain lifestyles and belief systems whose destruction is necessary for the revolution to be complete, total in nature, a complete rupturous change in the social order. these violent idealists destroyed everything in their path and used the revolutionary system to send their opponents to the firing squad, only to end up getting sent to the same fate themselves.

Hello Josh,

This digitized collection of Russian Futurist books is fantastic. Bravo! Here at the Getty Research Institute, we have digitized over 30 of the Futurist books — please go to http://www.getty.edu/research and under Library Catalogue (Primo) search any title that interests you.

If you don’t have it already, you might also be interested to know about my recent publication, EXPLODITY: SOUND, IMAGE, AND WORD IN RUSSIAN FUTURIST BOOK ART (Getty Publications, Dec. 2016). It is accompanied by an online interactive that shows pages from the books I analyze and readings of the poetry by Vladimir Paperny. http://www.getty.edu/ZaumPoetry

Congratulations!

Best,

Nancy

Dr. Nancy Perloff

Curator, Modern & Contemporary Collections

Getty Research Institute

1200 Getty Center Drive Suite 1100

Los Angeles, CA 90049–1688

See More