First published in three volumes in 1914, only 24 years after his death, the letters of Vincent Van Gogh have captivated lovers of his painting for over a century for the insights they offer into his creative bliss and anguish. They have also long been accorded the status of literature. “There is scarcely one letter by Van Gogh,” wrote W.H. Auden, “which I do not find fascinating.”

That first published collection consisted only of the painter’s 651 letters to his younger brother, Theo, who died six months after Vincent. Compiled and published by Theo’s wife, Johanna, Van Gogh’s correspondence became instrumental in spreading his fame as both an artist and as a chronicler of deep emotional experiences and religious and philosophical convictions.

Now available in a six-volume scholarly collection of 819 letters Vincent wrote to Theo and various family members and friends—as well as 83 letters he received—the full correspondence shows us a man who “could write very expressively and had a powerful ability to evoke a scene or landscape with well-chosen words.” So write the Van Gogh Museum, who also host all of those letters online, with thoroughly annotated English translations, manuscript facsimiles, and more. The collection dates from 1872—with a few mundane notes written to Theo—to Van Gogh’s last letter to his brother in July of 1890. “I’d really like to write to you about many things,” Vincent begins in that final communication, “but sense the pointlessness of it.” He ends the letter with an equally ominous sentiment: “Ah well, I risk my life for my own work and my reason has half foundered in it.”

In-between these very personal windows onto Van Gogh’s state of mind, we see the progression of his career. Early letters contain much discussion between him and Theo about the business of art (Vincent worked as an art dealer between 1869 and 1876). Endless money worries preoccupy the bulk of Vincent’s letters to his family. And there are later letters between Vincent and Paul Gaugin and painter Emile Bernard, almost exclusively about technique. Since he was “not in a dependent position” with artist friends as he was with family, in the few letters he exchanged with his peers, points out the Van Gogh Museum, “the sole focus was on art.”

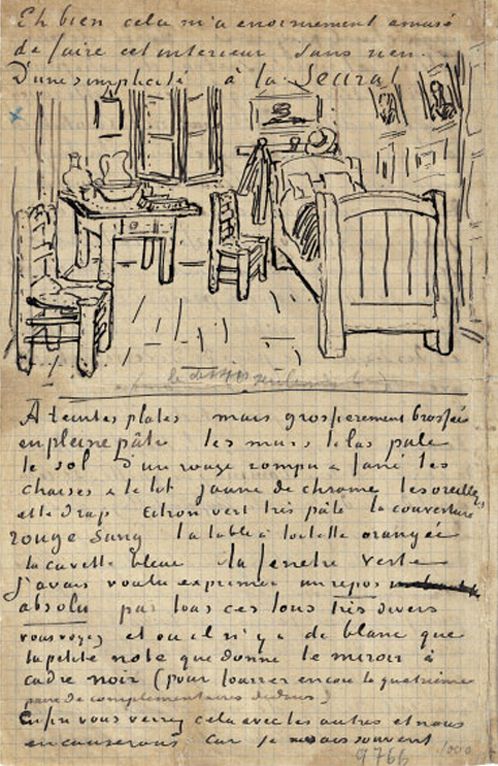

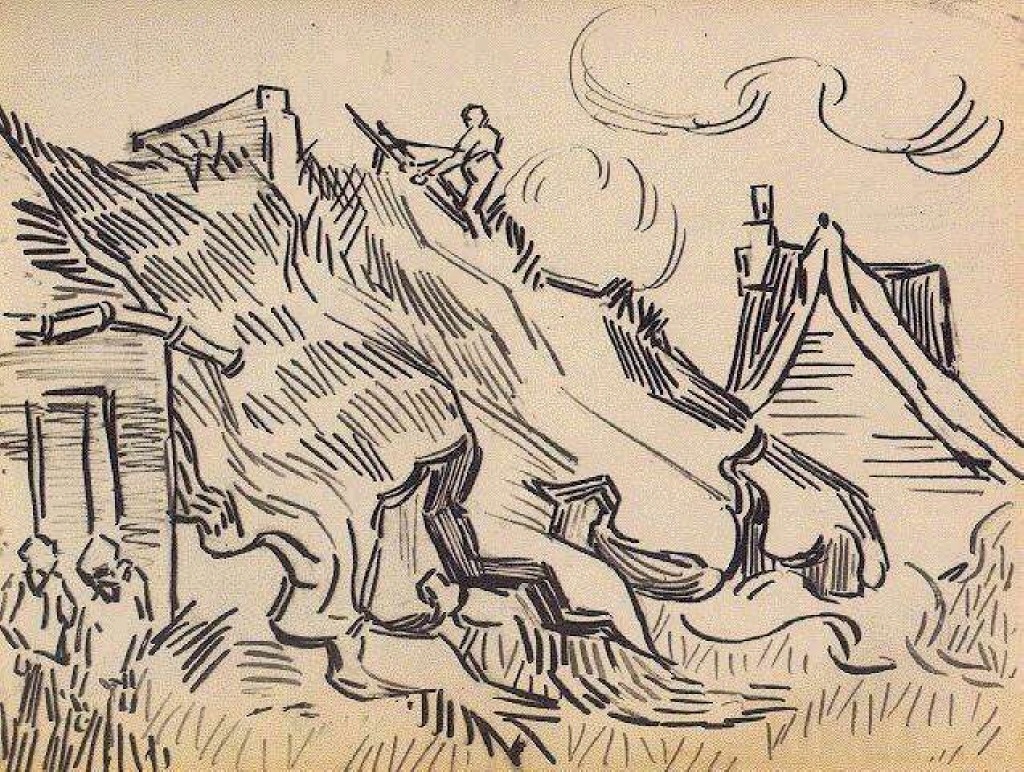

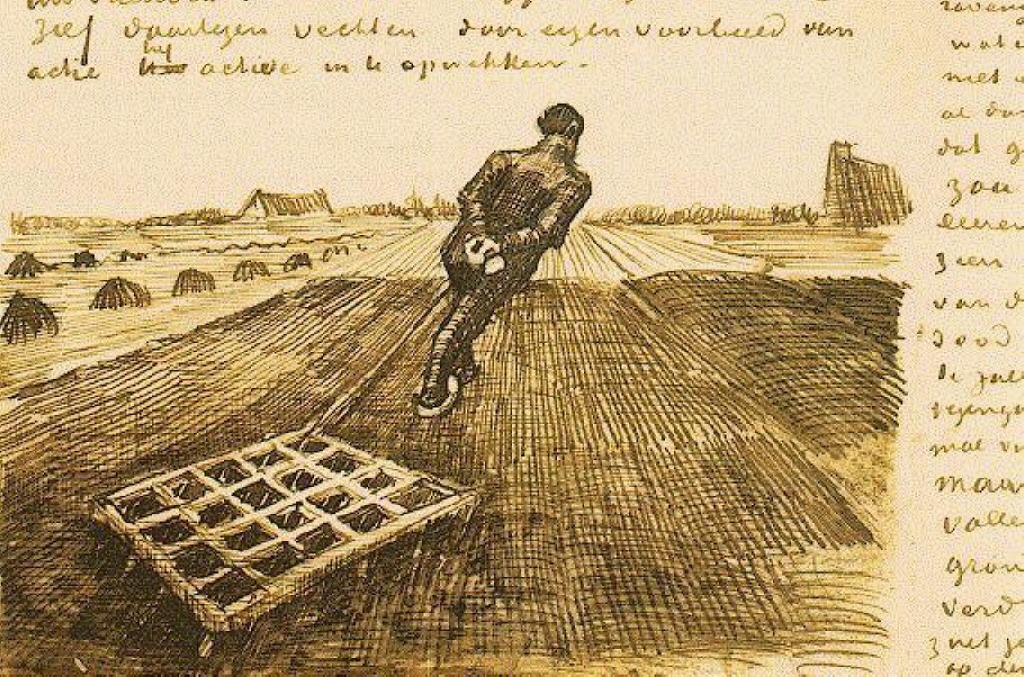

And as you can see here, Van Gogh would not only “evoke a scene or landscape” with words, but also with many dozens of illustrations. Many are sketches for paintings in progress, some quick observations and rapid portraits, and some fully-composed scenes. Van Gogh’s sketches “basically served one purpose, which was to give the recipient an idea of something that he was working on or had finished.” (See the sketch of his room in an 1888 letter to Gauguin at the top of the post.) In early letters to Theo, the sketches—which Vincent called “scratches”—also served to convince his younger brother and patron of his commitment and to demonstrate his progress. You can peruse all of the letters at your leisure here. Click on “With Sketches” to see the letters featuring illustrations.

And for much more context on the history of Van Gogh’s correspondence, see the Van Gogh Museum’s site for biographical information, essays on Van Gogh’s many themes, his rhetorical style, and the state and appearance of the manuscripts.

Related Content:

Download Hundreds of Van Gogh Paintings, Sketches & Letters in High Resolution

13 Van Gogh’s Paintings Painstakingly Brought to Life with 3D Animation & Visual Mapping

The Unexpected Math Behind Van Gogh’s “Starry Night”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Hello send me your e mail please I want to send you some pics . Thanks

Immensely interesting. It is amazing how great a draftsman Van Gogh was, how well he could draw a scene using cross-hatching and undulating parallel lines. And as Tchaikovsky was just as great and artistic a writer of literature as he was a musical composer, Van Gogh was also just as great and artistic a writer as he was a pictorial artist.